Since the summer is a time especially suited for travel, we’ve put together a collection of the ZYZZYVA team’s favorite works centered on the subject. Ranging from books thematically concerned with journey to ones that are simply perfect for reading in transit, we hope these picks will transport you––from an armchair at home or from one exciting locale to another.

Since the summer is a time especially suited for travel, we’ve put together a collection of the ZYZZYVA team’s favorite works centered on the subject. Ranging from books thematically concerned with journey to ones that are simply perfect for reading in transit, we hope these picks will transport you––from an armchair at home or from one exciting locale to another.

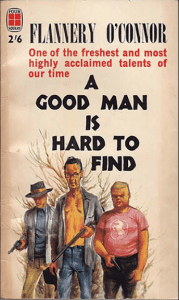

Caleigh Stephens, Intern: A word of advice to those embarking on road trips or other travels this summer—give a second thought before hurtling down that seemingly abandoned dirt path in rural Georgia at the behest of a grandmother’s nostalgia. However, don’t hesitate to pay a visit to the Southern gothicism of Flannery O’Connor’s first short story collection, A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories. Containing such stories as the titular piece, “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” and “Good Country People,” O’Connor depicts the deep South with her distinctive religious symbolism and apocalyptic commentary on the human condition. Though offering disparate vignettes, the stories are all grounded in the landscape they inhabit, infused with a strong sense of place. Her fiction binds the familiar with the foreign, adding a deep feeling of unease as appearances turn to deceptions. Thanks to masterful irony, the scattered violence and emphasis on the grotesque often add to the dark humor of the collection. The bizarre and comic nature of the collection also arises from a cast of characters who are as flawed as they are compelling. Caught up in their own hubris and naïveté, characters often find themselves in tragic and ironic situations of life or death. The book is imbued with O’Connor’s Catholicism as it often broaches questions of salvation, yet it also resides in a state of moral complexity. What is clear––O’Connor is a masterful storyteller, and her work is as enthralling as it is eerie.

Caleigh Stephens, Intern: A word of advice to those embarking on road trips or other travels this summer—give a second thought before hurtling down that seemingly abandoned dirt path in rural Georgia at the behest of a grandmother’s nostalgia. However, don’t hesitate to pay a visit to the Southern gothicism of Flannery O’Connor’s first short story collection, A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories. Containing such stories as the titular piece, “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” and “Good Country People,” O’Connor depicts the deep South with her distinctive religious symbolism and apocalyptic commentary on the human condition. Though offering disparate vignettes, the stories are all grounded in the landscape they inhabit, infused with a strong sense of place. Her fiction binds the familiar with the foreign, adding a deep feeling of unease as appearances turn to deceptions. Thanks to masterful irony, the scattered violence and emphasis on the grotesque often add to the dark humor of the collection. The bizarre and comic nature of the collection also arises from a cast of characters who are as flawed as they are compelling. Caught up in their own hubris and naïveté, characters often find themselves in tragic and ironic situations of life or death. The book is imbued with O’Connor’s Catholicism as it often broaches questions of salvation, yet it also resides in a state of moral complexity. What is clear––O’Connor is a masterful storyteller, and her work is as enthralling as it is eerie.

Angela Yin, Intern: Culture and travel, two things central to the summertime, are also central to Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats. In it, Jane Takagi-Little travels all over America, filming episodes for the Japanese show, My American Wife! In each episode, an upper-middle-class “wife,” typically white, teaches the audience a recipe for preparing meat while her two-point-five well-adjusted children play at her feet. Unsurprisingly, this layering of desires intended to create a desire that transcends a simple hunger for meat is sponsored by an American beef exportation company seeking a wider consumer base in Japan. When Jane rises in the ranks of the production crew, she alters the show’s direction, filming more diverse and non-traditional (though no less American) families. As she uncovers more of the dubious practices of the meat business, Jane must reckon, not with what she knows and doesn’t know, but with what she knows and has chosen to forget or ignore. In these days following the Fourth of July, with the smell of barbecue lingering in our backyards and American flags flapping in front of our houses and streaming from the backs of our cars, we need books like Ozeki’s My Year of Meats to remind us to question the history of these symbols, our voluntary ignorance, and what, exactly, it means to be an American.

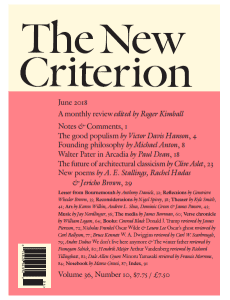

Ingrid Vega, Intern: In transit, journals always have room in my carry-on; but their svelte size does nothing to diminish the amount of erudition they can pack in one read. Other than ZYZZYVA (of course), The New Criterion has made its way to my travel bag. In 1982, this journal was born out of Matthew Arnold’s quote, “the best has been taught and said.” That statement challenged art critic Hilton Kramer and pianist Samuel Lipman to “experiment in critical audacity.” The journal brings in critics — both new and established — with the homologous aim of delivering the sharpest criticism of today. I especially adore The New Criterion for its music criticism. In the June 2018 issue, music critic Jay Nordlinger wrote “classical music is a minority taste,” in his article “New York Chronicle.” His writing — engaging and replete with the consistent sharpness that The New Criterion cultivates — also displays a satiating humility not commonly attributed to the intellectual community.

Ingrid Vega, Intern: In transit, journals always have room in my carry-on; but their svelte size does nothing to diminish the amount of erudition they can pack in one read. Other than ZYZZYVA (of course), The New Criterion has made its way to my travel bag. In 1982, this journal was born out of Matthew Arnold’s quote, “the best has been taught and said.” That statement challenged art critic Hilton Kramer and pianist Samuel Lipman to “experiment in critical audacity.” The journal brings in critics — both new and established — with the homologous aim of delivering the sharpest criticism of today. I especially adore The New Criterion for its music criticism. In the June 2018 issue, music critic Jay Nordlinger wrote “classical music is a minority taste,” in his article “New York Chronicle.” His writing — engaging and replete with the consistent sharpness that The New Criterion cultivates — also displays a satiating humility not commonly attributed to the intellectual community.

Throughout the “New York Chronicle,” Nordlinger expresses his admiration for Mahan Estefani, lauding him as an evangelist for the harpsichord; shares who he feels should succeed James Levine as the director of the Metropolitan Opera; and enlightens us concerning several recitals he recently attended by Russian pianists, Argentine cellists, and Latvian conductors. I harken back to Matthew Arnold’s philosophy while reading this journal: The New Criterion, for me, provides guidance as a young writer, as well as a satisfying consciousness of that “minority taste” and a reminder there are still people who care to disseminate it.

Claire Ogilvie, Intern: Whenever I am in transit (house moving, on vacation, or even during a long bus ride), I find comfort and connection in reading memoirs; in experiencing a journey in tandem with an author. One of my favorite and most repeated reads — especially for those summer months when reading becomes all the more languorous — is eminent rock critic Richard Goldstein’s 2015 cultural tour de force and crash-course in Sixties pop, Another Little Piece of My Heart. Goldstein’s memoir introduces readers to his lifelong love of rock music and counter-culture by way of his early twenties, when he spent his days traveling the country, pioneering of the art of rock criticism for the Village Voice. Goldstein is, refreshingly, most critical of himself; covering his early blunders and deep insecurities, as he elbowed his way backstage to conduct slapdash interviews with the likes of Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, and just about every other pop culture icon of the Sixties. Goldstein’s journalistic prose is peppered with self-effacing humor, filled with poignant recollections of the toll fame and drugs takes on an artistic soul, and brimming with the sincerity and wisdom of hindsight:

What sticks in my memory is the way he looked. Hendrix was stupefied, his shirt stained with what looked like caked puke. I listened to him mumbling for several minutes before leaving as graciously as I could. There was no publicist to make excuses or even wipe him up. I was tempted to put that meeting into print, but by then I had lost my distance from the musicians I wrote about. I’d learned to honor the feeling of empathy that they often aroused in me. There were two kinds of rock stars, it seemed: the survivors, such as Dylan and Jagger, who hid behind their personas, and those whose precarious egos marked them for ritual self-destruction. No way would I perform the journalistic equivalent of that nasty spectacle by blowing Jimi’s cover.

My copy is rightfully in tatters (the pages dog-eared and the cover faded from sun

exposure) after becoming a carry-on and poolside staple. Just as visceral after every reread, Goldstein chronicles the chaos of the Summer of Love, the Civil Rights movement, and Vietnam through the reactionary violence and poetry of the rock ’n’ roll revolution.

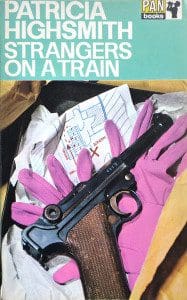

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: At the risk of being thunderingly obvious, Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 suspense classic Strangers on a Train stands out to me as a must-read while on the go. Sure, we’re all familiar with the Alfred Hitchcock film, which –– no doubt propelled by the ingenious hook of two men “trading” murders –– arrived in theaters only a year after the book, but it is Highsmith’s novel that is allowed to go even deeper and darker in both its psychological complexity and violence. With this, her debut work, Highsmith introduces many of the themes she would explore throughout her career, including morally dubious protagonists, homoerotic subtext, and noir-ish murder plots.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: At the risk of being thunderingly obvious, Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 suspense classic Strangers on a Train stands out to me as a must-read while on the go. Sure, we’re all familiar with the Alfred Hitchcock film, which –– no doubt propelled by the ingenious hook of two men “trading” murders –– arrived in theaters only a year after the book, but it is Highsmith’s novel that is allowed to go even deeper and darker in both its psychological complexity and violence. With this, her debut work, Highsmith introduces many of the themes she would explore throughout her career, including morally dubious protagonists, homoerotic subtext, and noir-ish murder plots.

When architect Guy Haines encounters charismatic playboy Charles Anthony Bruno on a train ride to Metcalfe, Georgia, he has no idea he’s about to be plunged into his own personal hell. The smooth-talking Bruno has a talent for quickly worming his way into strangers’ confidence, and soon learns of Guy’s unhappiness with his straying wife. Conveniently, Bruno himself is looking to get out from under the thumb of his domineering father, and suggests he and Guy swap murders, as the seemingly motiveless crimes would surely leave the authorities baffled. Guy is quick to rebuff his fellow passenger, but Bruno is not so easily deterred, and the budding psychopath becomes a long shadow darkening the step of Guy’s life as soon as he departs the train.

I’d wager much of the reason both the original book and Hitchcock’s adaptation continue to linger in the public imagination (Gone Girl director David Fincher has teased a remake as recently as 2015) is the way the concept underscores the inherent randomness and risk involved in travel. As soon as we set foot out our door, we give ourselves over to chance –– and the knowledge that the strangers we pass on the road, brush past on the train, or sit next to on a flight could just as easily be our next great love as our most insidious enemy; the particular brilliance of Highsmith’s novel is how Guy and Bruno’s obsessive game proves sometimes they can be both.

Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor: You couldn’t narrowly define the late Sergio Pitol’s “Trilogy of Memory” as just travel books. Yet the three volumes in his genre-defying series—The Art of Flight, The Journey, and The Magician of Vienna (translated into English by George Henson, and published by Deep Vellum)—are nonetheless invigorating travelogues

Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor: You couldn’t narrowly define the late Sergio Pitol’s “Trilogy of Memory” as just travel books. Yet the three volumes in his genre-defying series—The Art of Flight, The Journey, and The Magician of Vienna (translated into English by George Henson, and published by Deep Vellum)—are nonetheless invigorating travelogues

Pitol, who died in April at 85, was awarded both the Juan Rulfo Prize (in 1999) and the Cervantes Prize (in 2005, which he won for The Journey), making him one of the most acclaimed Spanish-language writers, as well as Mexican authors, of his era. The “Trilogy of Memory” describes, through what Henson aptly describes as a “collage technique,” Pitol’s formation as a writer, the blueprints of his novels and stories, and, for me, most enjoyably, his wanderlust. He finds himself in Central Europe, the Caucasus, and Russia, in Western Europe and China, sharing the company of an array of writers and poets, steeping himself in the literature of whatever nation he happens to be. (Pitol was also a translator, bringing into Spanish the works of Witold Gombrowicz, Jerzy Andrejewski, Henry James, Jane Austen, Giorgio Bassani, and many others.) Those meetings and relationships are winningly infused with an appreciation for the wonder of his vocation, and for the joys of culture and thought.

(Fortunately for Pitol, finding work in Mexico’s diplomatic corps gets him across the

globe niftily, as does having handy a valuable painting or a rare book to sell; any

writing about distant sojourns can’t help but remind, once again, that it’s incredibly

useful in life to have either a surfeit of money or of youth, which is to say time.)

But the travel in these books happens as much in the mind as on forlorn docks.

Pitol’s discursions on novels and stories are transporting. In fact, the distances

covered and worlds inhabited in his head are indistinguishable in their tangibility

from the streets and the rooms he inhabits abroad. The “Trilogy of Memory,” then,

conveys that other amazing aspect of travel, of time traversed. That’s a one-way

journey, of course. But if you’ve been looking behind and around you before the last

station comes into view, the scenery can be amazing.