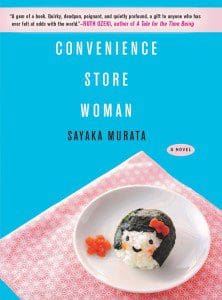

The Japanese word “Irrashaimasse” is an honorific expression used most often as a stock welcome in places of business. The spirit of the word is reflected throughout award-winning author Sayaka Murata’s novel Convenience Store Woman (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori; 176 pages; Grove Press), which invites readers to re-examine contemporary society’s absurdities through the idiosyncratic worldview of its narrator, 36-year-old Keiko Furukura. Murata perfectly portrays this unconventional woman who has been leading a stagnant life working at the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart since its opening 18 years ago. In the meantime, her friends are getting married and having children.

The Japanese word “Irrashaimasse” is an honorific expression used most often as a stock welcome in places of business. The spirit of the word is reflected throughout award-winning author Sayaka Murata’s novel Convenience Store Woman (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori; 176 pages; Grove Press), which invites readers to re-examine contemporary society’s absurdities through the idiosyncratic worldview of its narrator, 36-year-old Keiko Furukura. Murata perfectly portrays this unconventional woman who has been leading a stagnant life working at the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart since its opening 18 years ago. In the meantime, her friends are getting married and having children.

Furukura has never even been with a man, until an unlikely solution presents itself in the form of her new co-worker, Shiraha. Unfortunately, Shiraha is viewed as a societal parasite, a close-minded man who believes that the world is still “basically the stone age with a veneer of contemporary society,” and only took a job at the convenience store to find a wife. To little surprise, not only does he perform poorly, but he is eventually fired for his stalker-like behavior toward some of the female customers and employees. Furukura crosses paths with him again when she sees him outside the store and realizes he has been evicted from his place and is now homeless. She proposes a convenience marriage, which to Shiraha wasn’t ideal initially, but it is beneficial for both of them; this turns in to a quid-pro-quo situation as Shiraha only agrees to live with her if Furukura allows him to stay in the apartment. She can talk about him all she wants, but he doesn’t wish to be seen in public where he believes society will berate him for his choices.

Their relationship bears positive fruit in Furukura’s life: her co-workers invite her out for drinks, and her friends finally display some excitement instead of judgment toward her. She slowly tries to assimilate into society’s standards of a normal life—for instance, she considers bearing children with Shiraha—but the idea is stopped by a phone conversation with Shiraha’s sister-in-law. “Please don’t even consider it,” she tells her. “You’ll be doing us all a favor by not leaving your genes behind. That’s the best contribution to the human race you could make.”

Muriel Sparks wrote in A Good Comb, “There is nothing like work to calm your emotions,” and Furukura not only turns to work to calm her emotions, but to give her a sense of having some role in society. “I just come in every day,” she declares, “because I am accepted as a well-functioning part of the store.” She believes her very cells exist for the store, and so can never hope to leave her position.

Convenience Store Woman is a novel that proves sylphlike; spare in its contents, with a masterfully deceptive comic veneer that keeps the reader turning the page. Even with peculiar and macabre elements aplenty (as when a young Furukura wants to grill and eat a dead bird she finds on the ground), Murata has penned an unlikely feminist tale that unflinchingly depicts the social constructs of being a single woman.