In 2011, I was living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where I spent two years as the Kenan Visiting Writer shortly after the release of my first book, a story collection. One of these stories, “Bed Death,” appeared in the PEN/O.Henry Prize Stories, and it was this publication that led to my meeting Matthew Lansburgh. He sent me an email after reading it, and we struck up a friendship. In 2012, I moved back to San Francisco, and during a quick trip to New York in 2015, I finally met Matthew; we spent two days together, during which time he served as my “date” for a literary event.

In 2011, I was living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where I spent two years as the Kenan Visiting Writer shortly after the release of my first book, a story collection. One of these stories, “Bed Death,” appeared in the PEN/O.Henry Prize Stories, and it was this publication that led to my meeting Matthew Lansburgh. He sent me an email after reading it, and we struck up a friendship. In 2012, I moved back to San Francisco, and during a quick trip to New York in 2015, I finally met Matthew; we spent two days together, during which time he served as my “date” for a literary event.

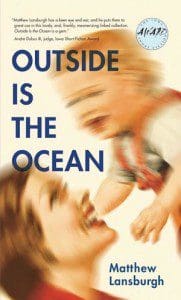

Later that month, he visited San Francisco, where he met Anne, my wife, who said that talking to him felt like talking to a brother. This sort of easy familiarity often exists between gays and lesbians, but we had numerous other things in common as well: all three of us are writers, of both stories and novels; we all write work that incorporates LGBTQ characters and themes without targeting a primarily gay audience; Matthew grew up in California, where we now live, and he lives in New York, where Anne grew up; his mother is from Germany, Anne’s from Vienna, and this informs their work, albeit in quite different ways. One of Matthew’s ongoing preoccupations in his work is the relationship between his main character, Stewart, a gay man who has moved from California to New York, and Heike, his German-born, overbearing mother. Outside Is the Ocean (192 pages; University of Iowa Press), which received the Iowa Short Fiction Award, is a collection of linked stories with Stewart and Heike at its heart. It is funny and heartbreaking and, as Publishers Weekly noted, it “succeed[s] as a nuanced character study and a resonant commentary on the challenges of romantic and familial love.” I read it in its entirety in a matter of days in manuscript form, and when the book landed in our mailbox, Anne devoured it just as quickly. Though Anne and I have similar aesthetics, we do not always respond with equal passion to books, but in Matthew’s case, we did, even when we discussed the book in private, which is, after all, what really counts.

Anne Raeff: When I was reading Outside Is the Ocean I was often overwhelmed by the sadness and desperation of the characters, but I never wanted to run away. I wanted to be overwhelmed by their desperation. I wanted to experience their weaknesses, their inability to connect, their pettiness, their humanity. Heike is, perhaps, one of the most human characters of modern literature. She wants so desperately to be loved, yet she does not know how to love. She is kind to animals and to people who are even more lost and isolated than she is, but she is cruel to those who are closest to her, who know her most intimately, who know her weaknesses. Perhaps, although she is an immigrant, a woman who came of age in Germany during World War II, she is the archetypal American—full of hope and ideals, yet, ultimately, so alone.

Lori and I interviewed Matthew about his book via email and Google Docs.

ZYZZYVA (Lori Ostlund): Let’s start the discussion with short stories. All three of us love short stories. We read them. We write them. You won the Iowa Short Fiction Award for this book. Anne and I have both received the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction (FOC). I once served as a screening judge for the FOC, so I know that it receives around 450 story collections a year for its annual contest. Contests (Drue Heinz, AWP Grace Paley Award, Sarabande’s Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction, Prairie Schooner Book Prize, BOA Short Fiction Prize) remain an important route to publication for story writers. Can you begin by describing the moment when you learned that you had won the award?

Matthew Lansburgh: I remember the moment vividly! I was walking toward my apartment on 28th Street in Manhattan. I was on the north side of the sidewalk, heading toward Sixth Avenue when I received an email from James McCoy, the editor of the University of Iowa Press, asking me to call him. At first, I had no idea who he was or what the email might be about. At the time, I was sending out stories constantly, and I wondered whether it was someone from The Iowa Review with a question about a story I’d submitted. I’d sent Outside Is the Ocean to the Iowa Short Fiction Award about five months earlier and hadn’t spent much time thinking about it in the interim. (I’ve always believed that the best way to maintain one’s sanity after sending something out to a journal or a contest is to forget about it and keep busy with other projects.)

Z: Was this the first time you had submitted to a story collection award? Can you explain a little bit about the process of getting to that moment?

ML: I’d been working on the collection, on and off, for a long time. It’s hard for me to calculate exactly how long, since some of the earliest stories were pieces I’d tinkered with when I was first learning how to “write a story.” In 2012 and 2013, I’d submitted a very early version of the collection to some agents and, though I’d received some encouraging feedback, nearly everyone said “collections are impossible to sell; contact me when you have a novel.” At that point, I put the book aside and starting working on a novel.

Often, however, when I hit a roadblock in the novel, I’d come back to the collection and revise one or two of the stories. I never forgot about it. Sometimes, I’d wake up in the middle of the night with an insight about how to change the ending of one of the stories or how to change the beginning of another. At some point in the process, I decided to submit the collection to some of the national contests. I’d submitted it to both the Flannery O’Connor Award and the Iowa Short Fiction Award previously, though by that point most of me had given up hope that it would ever be published. My partner, Stan, who’d been hearing me talk about the collection forever, kept telling me it was time to move on.

Z: There is a good lesson in what you write here, Matthew, about the need to keep submitting, even to the same contests. I think that writers don’t always realize that contests change screening judges yearly in most cases, which means that a collection might get submitted several times before “suddenly” breaking through to the guest judge or series editor and, as in your case, winning the award. This was the case with Anne as well.

When my own collection was about to launch, I went into a bit of a funk, thinking about the fact that my book was finally going to be out in the world with all of the attendant fears that come with publishing one’s first book. But, as you know, my biggest fear had to do with my parents. They already knew that I was a lesbian and not religious, which together formed the basis of our ongoing conflict, but somehow it frightened me much more to know that they would be able to read my book and, in doing so, have access to the real me, to how I think and feel about the world. What was your biggest fear as you thought about your book heading into the world?

ML: Mostly what I felt, what I still feel, is tremendous gratitude. So many writers—talented writers who work hard—aren’t able to publish a book. When I first started writing literary fiction, I had no appreciation for how incredibly difficult it is to publish. I didn’t realize that journals receive hundreds, sometimes thousands, of submissions for every story they take. So the overwhelming feeling leading up to the book’s publication was happiness and gratitude and, frankly, relief. I’d gotten to the point where I wasn’t sure I’d actually publish a book, had started reconciling myself to being one of those people who hopes to publish but never quite makes it. I think I woke up just about every single day during 2017 thinking: this is what happiness feels like, this is what it’s like to feel okay about yourself. I know it sounds corny and overstated, but it’s true. I turned 50 right before I’d received the news from Iowa, and it was a really tough birthday. Friends of mine who’d turned 50 around then had posted photos on Facebook of huge parties and glamorous trips, and I really had no interest in celebrating anything—at that point, I saw myself, to some extent, as a failure. Then, just weeks later, I felt like I’d just won the lottery.

Of course, this doesn’t mean I didn’t find things to worry about leading up to the book’s publication. Indeed, I am an expert worrier—one of the best around! I spent some time worrying about the usual things (will people like the book? will the cover be okay or will it just be a drawing of a couch?) I’ve also spent a considerable amount of time trying to decide whether I should tell my mother about the book.

Z: And did you end up telling her?

ML: No, I haven’t told her yet. It’s an issue I’ve struggled with for some time. Of course, part of me would love to share the news with her. She’s always been incredibly supportive of my writing and always asks whether I’ve written any new stories for her to read. Several years ago, I shared a few of the stories from the collection with her, but the other stories have remained a secret because I’m afraid they might make her upset, even though people who’ve read the book often tell me they think I’ve presented Heike very sympathetically, that they like how three-dimensional she is. Although the circumstances and details involving Stewart and Heike are invented, my mother is similar enough to Heike that it’s possible she would find some of the material disturbing.

Z: According to the American Booksellers Association, “Retail sales at U.S. bookstores were down by 6.6 percent in September 2017 compared to September 2016, according to preliminary figures recently released by the Bureau of the Census.” If my Facebook friends, many of them writers, almost all of them readers, are any measure, perhaps this has partly to do with the fact that people have lost their attention spans or are so consumed by the news that nothing else seems to matter. How did it feel to come out with your first book in such turbulent times?

ML: Without a doubt—in addition to any concerns I might have had that were specific to my own situation and the particulars of Outside Is the Ocean, I definitely also faced (am facing) the same macro concerns so many other writers are grappling with these days: how do we persuade people to devote ten or fifteen or twenty hours to reading a book? I myself find it harder than ever to carve time out to read books. As has been discussed ad nauseum at this point, people seem to have less and less time and more and more distractions—CNN, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter (and its constant reminders about the shenanigans in the White House and the state of America’s political situation). It’s hard to unplug and lose oneself in a book—especially when there are so many high-stakes battles unfolding in our country (indeed, in the world) these days.

There were definitely weeks when I felt that my preoccupations related to how people were receiving my book felt incredibly self-indulgent and myopic, given the horrific news that seemed to be unfolding constantly during 2017. Did it really matter how many people had reviewed my book on Amazon when the EPA was being decimated and Trump was trying to dismantle the Affordable Care Act? Whenever I expressed this concern, my friends often responded in the most generous way imaginable: telling me that the publication of my book represented a bit of good news in an otherwise bleak cycle of political developments. Hearing that people connected with Outside Is the Ocean and found it moving has meant so much to me and has helped get me through an otherwise very difficult year.

In some ways I think your question touches on the age-old question that artists must always ask themselves: What is the purpose of art? Is making art a productive use of time when there is so much suffering and injustice in the world? I don’t pretend to have answers to these questions, and I often feel like devoting so much of my life to writing and rewriting sentences about imaginary people is indeed self-indulgent. On the other hand, I know that reading a novel or a story that resonates for me emotionally can be an incredibly powerful experience and can, at times, help me both to feel less alone and to feel more empathy for other people. On good days, I still believe art can help us to become the best versions of ourselves.

Z: In some ways the “star” of your collection is Heike, Stewart’s flamboyant, demanding, annoying, frustrating, overwhelming, and also heartbreaking mother. Heike grew up in Germany and came to the United States as a young woman in the 1950s, after having experienced the war years as a child. To what extent did you draw from your own mother’s experiences? Did your mother tell you stories about her childhood in Germany? How did those stories shape how you perceived your role as a storyteller?

Z: In some ways the “star” of your collection is Heike, Stewart’s flamboyant, demanding, annoying, frustrating, overwhelming, and also heartbreaking mother. Heike grew up in Germany and came to the United States as a young woman in the 1950s, after having experienced the war years as a child. To what extent did you draw from your own mother’s experiences? Did your mother tell you stories about her childhood in Germany? How did those stories shape how you perceived your role as a storyteller?

ML: You’ve packed a lot into this question, Lori, so apologies in advance if my answer is involved. As I mention above, Outside Is the Ocean is fiction, but the book was certainly inspired by events from my life and from my mother’s life. Like Heike, my mother grew up in Germany during WWII and emigrated to the United States as a young woman. Some of the stories that Heike tells Stewart in my book are, indeed, based on stories my mother told me.

Many readers, myself included, often want to know how much of a work of fiction is based on actual events. In the case of Outside Is the Ocean, despite the fact that the initial inspiration for the book was my mother, the final result bears little relation to actual events in her life or mine. Some of the emotional currents that define Stewart’s relationship with Heike define my relationship with my own mother, but the events in the book and the specific circumstances the characters encounter grew out of my imagination. The reason for this isn’t a noble attempt on my part to “protect the innocent,” but rather stems from the fact that fiction allowed me to tell stories that had a shape and cohesion that don’t exist in real life. Indeed, early on, when I first tried to write about my relationship with my parents in something that I thought might be more of a memoir, people often told me that the material felt flat and didn’t have enough tension to create a compelling narrative.

The process of taking the raw material of my life and turning it into “literature” was, as you and Anne know, incredibly difficult and involved a tremendous amount of trial and error. Some of the stories in the collection probably went through close to 100 drafts.

As for how my mother’s stories shaped my perception of myself as a storyteller, I must say, I have no idea … I consider myself pretty self-aware, and yet that isn’t something I’ve actually thought about before. It might sound strange to admit this—given how much of my life I’ve devoted to writing—but the fact is I don’t really consider myself a “storyteller.” My mother is definitely a person who likes to tell stories. She can turn the smallest event in her day into an engaging narrative with conflict and stakes and humor. She loves to be the center of attention. I’m quite different, however: in most situations I don’t like to tell stories orally, and when I’m the center of attention, I can often feel quite self-conscious. For some reason, I don’t really think of writing as “telling a story.” I think of it as something else—perhaps creating a world over a long period of time through the slow accretion of words? The end result might be a “story” but the process is so slow and iterative that it never feels to me like I’ve “told” a story. Does that make sense? Do you think of yourself as someone who tells stories?

Z: I suppose I do think of myself as someone who tells stories, and I’m drawn to people who tell stories as well. Often, when I’m asked a question, I prefer to answer with a story that—at least to my mind—gets at something that I find myself unable to articulate except at the metaphoric or narrative level. Perhaps this is why I abandoned my dreams of a life in academia early on. I do like what you say about the story evolving, via “the slow accretion of words,” over such a long period that it doesn’t feel to you like “telling a story.” Still, I don’t think of you as someone who doesn’t tell stories. When I think of our friendship, in fact, I think of certain stories that you’ve told me. Perhaps your discomfort with the label storyteller has to do with the fact that your mother embraces the title? Do you see oral storytelling as more off the cuff, less intentional, and therefore less meaningful perhaps?

ML: I love the notion of answering a question with a story—perhaps this is a sign that you’re approaching enlightenment? It seems like something a Zen master would do.

I wouldn’t say that composing a story on the page seems more meaningful to me than telling a story orally, but I do see oral storytelling as somehow more “authoritative”—at least at the moment of composition. The act of writing is, I think, for most writers, an iterative act—we revise again and again, we test one phrasing, then another. For me, it feels very unstable. My perception of oral storytelling is that the narrator speaks with more certainty and less self-consciousness. The oral narrator can’t revise and backtrack as much as the writer in front of her computer; doing so risks jeopardizing one’s authority. The oral story must, I think, be told as if it were the truth and can’t be told in any other way. I know that I’m a person who can and does tell stories orally, but I think this posture often makes me feel self-conscious and uncomfortable. In many circumstances, I feel much more comfortable writing than speaking.

As for the impact my mother’s ability to tell stories has or might have had on me, this is the kind of question that fills me with great sadness. For decades, my mother has accused me of developing a taste and sensibility in opposition to her. (“Why don’t you want to put margarine on your sandwich? It’s because that’s something I like, isn’t it?”) While it’s true that my mother and I have had a rocky relationship, I do care for her deeply. My failure to navigate my relationship with her successfully has caused and will always cause me a great deal of pain. Sometimes, as I grow older and older, I see the ways in which she and I are quite similar, and I am—by turns—horrified, amused, befuddled.

Z (Anne Raeff): I loved the way you reproduced Heike’s syntax in English, the little things that people who are not native speakers do with language. It really helped bring her alive for me, especially since I grew up around people whose English was full of such idiosyncrasies. My father, for example, took gas instead of got gas. My grandmother could not use an article to save her life. So, my question is, how much German do you know and how does German, what you know and what you don’t know, figure as a muse or anti-muse for your writing? Did growing up with someone who was not a native speaker affect your writing, your prose? For me German brings a certain nostalgia. Does it have that effect on you, too? Do you get teary eyed when you think of “Hoppa Hoppa Reiter?” I do.

ML: I don’t speak German, but I’ve always been fascinated by the way my mother expresses herself—by her syntax and diction; there’ve been times when I’ve literally run into the bathroom when she finishes telling a story so I can write down certain expressions she used. Many years ago there was a period when I recorded her while she told me stories so that I could transcribe what she said. This fascination with the way foreigners express themselves has definitely carried over to other writing projects of mine. I often find myself drawn to characters who express themselves in interesting ways. As for getting teary-eyed when I think of that nursery rhyme, the answer is yes; I get teary-eyed a lot when I think about my mother.

Z (Lori Ostlund): We three represent three perspectives on what it means to be LGBTQ writers today, and we are also friends. How do you view the relationship between gay and lesbian writers? Do you think that it parallels the relationship between male and female writers? Do you think that there is a common ground between gay and lesbian writers?

ML: These are fascinating questions, Lori, and I’m hoping you and Anne will share your thoughts about this as well. To be honest, this isn’t something I’ve thought a lot about. My initial answer is that I don’t think of myself as a “gay writer” per se, and I’ve never thought of you and Anne as “lesbian writers.” I’m not entirely sure why that is—probably because homosexuality doesn’t seem to be as central to our work as it is for certain other writers. I think the writers I align with most closely and whose work I feel most inspired by are people who care deeply about examining the nuances of relationships and the way individuals navigate the ways in which all of us can feel different from, and alienated by, those around us. Some writers who are gay/lesbian care about those issues; some don’t. And, of course, gender doesn’t necessarily have much to do with this, either. As far as I can tell, my favorite writers (including Flannery O’Connor, Alice Munro, Mavis Gallant, Anthony Doerr, J.M. Coetzee, Kazuo Ishiguro, J.D. Salinger, Lorrie Moore, V. Nabokov, George Saunders, Adam Haslett, Jhumpa Lahiri) don’t cluster in any particular silo.

Z (Lori Ostlund): I think that my preoccupations are also not defined solely or even largely by sexual orientation, though that does not mean that my experiences as a lesbian haven’t deeply affected the way that I view everything, including interactions with others and loneliness and the human need to connect. They have. Even in my own life, they are central to the relationship I have (or don’t have) with my family.

At this point in my writing life, I am tired of the notion that writing that deals with LGBTQ characters must be about coming out and must somehow let these characters off the hook more easily—as if all we do is sit around “coming out” and as if we are not just as deeply flawed as everyone else. That is not to say that I’m not interested in work that deals with the experience of coming out—I am—and I also think that, for writers, writing about the coming-out process provides something essential: automatic conflict. However, I also suspect that there is a tendency among readers (especially non-LGBTQ readers) to believe that unless the work is explicitly about a character coming out (or transitioning), the characters should default to being straight. In fact, before my last book, After the Parade, came out (I’m going to leave the pun in), one of the first posts to appear on Goodreads (yes, I looked at Goodreads and still do on occasion) was by a man who lowered the number of stars because he said that there was no reason to make Aaron, my main character, gay since he wasn’t coming out in the book—as if the bullying he had endured and his subsequent loneliness and affinity for misfits were not all directly related to his being gay.

As for the second point that I raised above, the idea that LGBTQ characters should be held to different standards—less flawed or capable of doing “bad” things—I understand why this happened. (We all can recall numerous examples of the stock movie villain who is effeminate, for example.) But I think that we are ready to move beyond this: we need to, in fact, or we limit ourselves to LGBTQ characters who are less nuanced and complicated than other human beings.

ML: Your response triggers a feeling that I’ve always had but don’t think I’ve ever actually put into words: being gay has defined and shaped who I am and how I see the world in profound ways, but it is just one part of my identity. My writing is an effort to understand the totality of my experience, including (but not limited to) my sexuality.