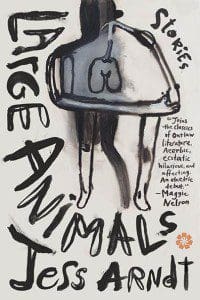

Jess Arndt’s Large Animals (131 pages; Catapult) traps its characters in self-constructed cages and puts them on display, presenting a bevy of cultural concerns about identity, sex, and the human body. Ranging from the 19th century to contemporary San Francisco and New York, the twelve stories in Arndt’s first book prove startling in their variety and verisimilitude, and challenge our notions of gender and the binary divides that too often fail to define us.

Jess Arndt’s Large Animals (131 pages; Catapult) traps its characters in self-constructed cages and puts them on display, presenting a bevy of cultural concerns about identity, sex, and the human body. Ranging from the 19th century to contemporary San Francisco and New York, the twelve stories in Arndt’s first book prove startling in their variety and verisimilitude, and challenge our notions of gender and the binary divides that too often fail to define us.

In “Beside Myself,” we witness the austere life of a woman attempting to impregnate her wife by using her brother’s sperm. Here, as in many of the stories, the reader inhabits the aching body of the protagonist, and empathizes with her while questioning one’s own physical insecurities as the narrator morosely remarks, “among all life-forms, humans alone [are] defenseless-vulnerable blobs clothed solely in skin.” A blend of the bizarre and believable, every story in Large Animals is voiced by individuals battered by the daily toil of living as outsiders. No story captures this motif more than the title story, wherein the narrator’s mundane life is disrupted by recurring nightmares of animals in her bedroom. As the animals become a burgeoning obsession, they develop an order in her dreams, a kingdom with a bestial hierarchy in which the “massive, tube-shaped” walrus reigns. When the walrus speaks, its words are obscene but devoid of context. The narrator’s nocturnal encounters rapidly deteriorate her life, revealing her dormant sexuality and animalistic lust towards a fast-food worker even as she struggles through a vicious divorce.

And in its short shorts like “Containers,” where a decision to stay home and smoke weed rather than party with friends compartmentalizes an identity crisis in less than three pages, Large Animals proves wickedly entertaining. These are modern fables of the body exposing a naked perspective on femininity, masculinity, and the need — or lack thereof — for human relationships.

Carnal and experimental in tone, expressed in Arndt’s beguilingly casual and frequently colloquial prose, Large Animals is equally vivid in its depiction of human vulgarities as in its exploration of the body. It prowls through our preconceptions of the sexes, paring back its fallible, idiosyncratic character to render a raw and unnerving portrait of the self. “Animals are only animals because they are observed,” one character says, and here Arndt observes the largest animal, exhibiting our fears and our instincts.