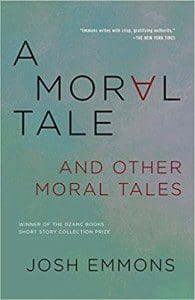

The past is never past in Josh Emmons’ new story collection, A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales (184 pages; Dzanc Books). In each of these stories (of which the title one appeared in ZYZZYVA No. 102), the reader can feel the lingering effect of humanity’s fabricated history – the assemblage of folktales, parables, and lore that have helped shape our collective consciousness over time, from Noah and his Ark (“Haley”) to Aesop’s talking animals (“Arise”).

The past is never past in Josh Emmons’ new story collection, A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales (184 pages; Dzanc Books). In each of these stories (of which the title one appeared in ZYZZYVA No. 102), the reader can feel the lingering effect of humanity’s fabricated history – the assemblage of folktales, parables, and lore that have helped shape our collective consciousness over time, from Noah and his Ark (“Haley”) to Aesop’s talking animals (“Arise”).

The narrator of one piece claims, “What came next hardly warrants retelling, so familiar is the story…” but nothing could be further from the truth, as Emmons possesses an uncanny gift to make the distant, half-remembered folktales of our childhoods feel both present and unexpected. In “Nu,” we observe a woman who is afraid of cats, in part because of what they represented to the ancient Egyptians, and characters throughout the collection frequently compare their lives to fables (“…real life is less frightening than fairy tales. And less exciting. And there’s no way to know which is better”). These drifting souls search for meaning and connection across a variety of settings, whether it’s modern day France (“A Moral Tale”) or medieval England (“Humphrey Dempsey”). The result of their foibles comprises one of the most dazzling and assured story collections of the year.

Emmons talked to ZYZZYVA about A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales, as well as what draws him to fairy tales and his mix-tape-making process.

ZYZZYVA: In A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales, you have several stories that take place in current settings in which one can feel myth and fables pressing upon contemporary events. I sense that, as a writer, you believe the fables and fairy tales many of us grew up with continue to be relevant to our lives. What drew you to incorporating or referencing fables in your work?

Josh Emmons: I stopped thinking about fables and fairy tales and myths in my late teens—When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things—and came back to them in my twenties because they were inescapable. There was Kafka’s “The Burrow” casting animal stories in a new light, for example, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice books redeeming nursery rhyme tropes, and “Ulysses” and “East of Eden” and “Master and Margarita” showing that repurposed myths could be fascinating. I think fairy tales get a bad rap because they deal with radical innocence and radical evil—melodrama, basically—and so lack subtlety. Also they’re overfamiliar and crudely written and outrageously plotted, but for many of those same reasons they’re fun to rethink and reconfigure. And they address deep, elemental, archetypal phenomena, which is appealing for a Joseph Campbell fan like me. And despite all the fairy tale revisionists out there, humorless Angela Carter and careless Salman Rushdie and frantic mash-up writers at Disney and Dreamworks, they’re inexhaustible. Folk traditions might be barbaric, but they’re malleable and never dull.

Z: On that note, I was thinking about the freedom you obtain by calling this book A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales rather than A Moral Tale and Other Stories. “Tale” seems to indicate these stories are going to be taking place on a more figurative level, perhaps dealing with mythic beings or archetypal figures, such as in “Sunrise” when we see characters simply called Husband and Wife. Did you put a lot of thought into framing the book as … and Other Moral Tales?

JE: Some of the stories predate the title work, so I had to rename them tales after the fact, but I wrote others, like “Agape” and “Sunrise,” with the title in mind. It’s not so much that I wanted every story to pose a big moral dilemma, but that their characters’ lives are full of decisions that seem, and sometimes are, overly significant. Should I sleep with this person? How will my conscience react if I cast the deciding vote? Did I make a mistake by going after money instead of art? I hope all of these stories work as both literal accounts and allegorical gestures. I might agree with Nabokov that art only has one responsibility, to provide aesthetic bliss, but I also think it’s most urgent when probing questions of right and wrong, however relative and fluid those terms are. And there’s a heavy irony to the title: the stories are all called moral, and some mete out harsh justice to transgressors, but none actually prescribe or proscribe anything. If you look at “Sunrise,” a man who plots to kill his wife is arrested for her murder at the end, but only after he’s repented and tried desperately to save her life. Cause and effect get confused, and nuances pile up until it’s hard to see over them, at which point, remarkably, characters can make good decisions almost in spite of themselves.

JE: Some of the stories predate the title work, so I had to rename them tales after the fact, but I wrote others, like “Agape” and “Sunrise,” with the title in mind. It’s not so much that I wanted every story to pose a big moral dilemma, but that their characters’ lives are full of decisions that seem, and sometimes are, overly significant. Should I sleep with this person? How will my conscience react if I cast the deciding vote? Did I make a mistake by going after money instead of art? I hope all of these stories work as both literal accounts and allegorical gestures. I might agree with Nabokov that art only has one responsibility, to provide aesthetic bliss, but I also think it’s most urgent when probing questions of right and wrong, however relative and fluid those terms are. And there’s a heavy irony to the title: the stories are all called moral, and some mete out harsh justice to transgressors, but none actually prescribe or proscribe anything. If you look at “Sunrise,” a man who plots to kill his wife is arrested for her murder at the end, but only after he’s repented and tried desperately to save her life. Cause and effect get confused, and nuances pile up until it’s hard to see over them, at which point, remarkably, characters can make good decisions almost in spite of themselves.

Z: Early in “Concord,” which is one of my favorite stories in the collection, you utilize paragraph breaks to fluidly leap from tangentially related characters in a way that’s both audacious and novelistic. I say audacious in part because I had no idea if the story was going to eventually loop back to the character, Cameron, who opens the piece. Was the technique of leap-frogging characters the genesis of the piece or something that happened organically while writing?

JE: The leap-frogging happened as I wrote it. Cameron was based on a friend of mine who’d quit making music after college in order to work in finance. Looking back on it, I don’t think this was so tragic or surprising—making a living as a musician is hard—but at the time it seemed like he’d sold out. I wrote “Concord” to rescue and redeem him, which sounds ridiculous, and figured that the best way to do that was through love, and because love stories need big obstacles and even bigger coincidences, and because I like moving between characters’ heads as a reader and a writer, I brought in Tsitsi and Ryan and Janet, the other points on the love quadrangle. Love is a communal act even if it’s cynically considered by some to be a self-generated, solitary delusion.

Z: Since you’re a novelist in addition to a short story writer, how do you decide if a piece like “Concord” is best served as a short story rather than in a longer form like a novel or novella?

JE: Slight plots can provide enough substance for a long novel and epic events can be squeezed into a short story, so I make the “novel or short story” decision based less on the amount of action there’ll be than by how long I want to spend with certain characters in a certain world. As with relationships, it all comes down to, “Do I like it enough to stay?” Not that I ever know at the beginning how I’ll feel about it later. I mean, I’ll have an idea, but ideas are just ideas until they become something else.

Z: I would be remiss if I didn’t touch on “Humphrey Dempsey,” which—along with “Arising”—might be the most explicit in its exploration of fables and fairy tales, since you utilize two non-human characters. Was there any hesitation in including these more fantastical stories alongside a place like “Concord,” which is set in present day San Francisco, or did you find that they complemented each other in some way as you were assembling the collection?

JE: Way before Spotify playlists and “Master of None” soundtracks and the new eclecticism, I made a mix-tape for my younger brother and followed a peaceful Miles Davis song from “Porgy and Bess,” a slow-building, lone-horn-lifting-its-voice-to-heaven number called “Prayer (Oh, Doctor Jesus),” with an aggravated, jackhammering techno song by 808 State called “Time Bomb,” so no. Strange bedfellows can have fun together. I love Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler… because the dissatisfactions that come from being pulled, sometimes gently but more often violently, from one mood and sensibility to another are compensated for by the thrill of novelty and discovery. Heterogeneity rather than homogeneity. There are strong linked story collections where a common voice or character is great, a Jesus’ Son or Bad Behavior, but I wanted this collection to offer a broad range of atmospheres. And since fiction is always partly an anthropological act, a document of a place’s mores that will soon look like peculiarities, present-day San Francisco and mythical Middle Ages kingdoms aren’t really so dissimilar. Provided the rents were reasonable, we could live happily in either.