Somewhere along the way, confessional poetry developed a bad rap. Perhaps it was the result of ubiquity: by 2003, every other turn of the radio dial delivered a soul-baring lyric to one’s ears (“On the way home this car hears my confessions,” went a lyric from a band literally called Dashboard Confessional), and college freshman creative writing classes were inundated with impressionable students expressing their angst through pen and paper. (You may have sat next to one, you may have been one yourself.) These days, mediums such as Facebook, Tumblr, and, well, Medium allow us to broadcast our inner lives to close friends and complete strangers alike—these digital walls can talk.

Somewhere along the way, confessional poetry developed a bad rap. Perhaps it was the result of ubiquity: by 2003, every other turn of the radio dial delivered a soul-baring lyric to one’s ears (“On the way home this car hears my confessions,” went a lyric from a band literally called Dashboard Confessional), and college freshman creative writing classes were inundated with impressionable students expressing their angst through pen and paper. (You may have sat next to one, you may have been one yourself.) These days, mediums such as Facebook, Tumblr, and, well, Medium allow us to broadcast our inner lives to close friends and complete strangers alike—these digital walls can talk.

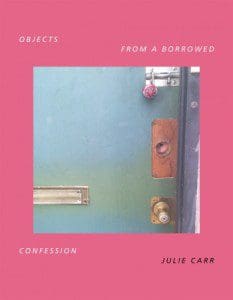

Considering the way modern technology has made the act of confession an almost thoughtless and arbitrary pastime, academic circles may have felt they had no choice but to turn their noses up at this ever-growing portion of the poetry world. But it’s a corner that clearly has long fascinated celebrated poet and author Julie Carr: “I wanted to think about what the Language Poets and the Conceptual Poets had against ‘confession,’ but I also wanted to see why confession was so important to our broader culture,” she writes in the Author Statement of her newest book, Objects From a Borrowed Confession (Ahsahta Press; 149 pages), a collection of pieces that tackle the notion of confession from a unique angle. “I wanted to explore that impulse and the attraction we have to one another’s secrets…I wanted to understand what the act of confession has to do with intimacy, empathy, and subjectivity.”

Carr, who earned her doctorate at UC Berkeley, is the author of six books of poetry, including 2010’s acclaimed 100 Notes on Violence. With her latest work, Carr moves seamlessly among genres ranging from poetry, memoir, flash fiction, and essay. Indeed, one of the chief pleasures of the book is its amorphous quality. Carr describes the opener, titled “What Do We Want to Know,” as “an epistolary novella written from the point of view of one woman to her ex-lover’s ex-lover.” The piece establishes many of the currents running through Objects, including Carr’s shimmering wordplay (“Every day resolves itself in language, like insects running across snow, or like the premonitions of Philip Glass heard through a pillow”), as well as her frequent references to other poets and writers, including Gustav Flaubert and Herman Melville.

True to her interest in confession, Carr writes frankly about her children, who offer many of the book’s most touching and humorous moments. (“Today my ten year-old daughter told me, while doing some Lady Gaga moves in the kitchen, that she had just two things to look forward to: owning a credit card and sitting in the front seat.”) She also writes of her sexual attraction to men other than her husband, thought it must be said the project never enters the realm of the salacious. Rather, Carr draws the reader close like a confidant; this sensation bolstered by the knowledge she spent a decade compiling the various sections in Objects. As such, the collection feels like a record of her thoughts and fixations during some of the most intense periods of her life—to the point that, for many readers, Objects may have less to do with Carr’s exploration of confession and more with her creating a sense of intimacy.

Particularly harrowing is a later section titled “By Beauty and by Fear: On Narrative Time,” an essay in which Carr partly chronicles the year she spent writing 100 Notes on Violence, a period defined by her bouts with insomnia and her grief at losing her mother to Alzheimer’s disease: “One morning the sky was all Easter, so pink and salmon, so baby blue, I thought it must be kidding. Going for a walk, making a meal, it all seemed obscene.”

It’s partly because of these intense sections that Carr includes a few of Objects’ shorter movements so as to “offer a reprieve from the heavier topics of other essays”; however, even in the darkest pieces, she has an ability to keep each sequence grounded in day-to-day reality, such as when, in the midst of examining the increasing blur between video games and war-like violence, Carr stops to note, “…when mid-sized, my son and his friend would have played Pokémon for fifteen hours without stopping if we’d let them.”

Thanks to tangible moments such as these, the reader rarely forgets the weight of their responsibilities as parents, spouses, lovers, and friends, no matter how heady the discussion becomes. Carr engages in philosophical ruminations without losing sight of how these ideas affect our lived experience, as when the act of getting her son’s zombie costume ready on Halloween leads her to remember the many friends who have lost children: “Something terrible happened when I applied the dead-flesh makeup to his skin: he looked dead and I wanted to sob.”

Objects From a Borrowed Confession might ask us to view it through the lens of our society’s fascination with confession, but this ten-year project encapsulates much more. The book feels haunted by the spiritual loneliness brought on by the death of a parent; in examining the confessional streak dominating our culture—from song lyrics to Facebook feeds—Carr decides we confess as a testament to our will to live: “What I confess to here is also nothing more or less than my aliveness. Why would I need to confess this: I am alive? Because I’m a child who outlives her mother.” Despite being compiled over many years, Objects never reads as a threadbare or disparate scrapbook. Its melding of genres and narrative threads is encased in Julie Carr’s distinctive voice and sensitive intellect. It’s a testament to both that such an ambitious literary project still manages to seem like an intimate conversation with a close friend.