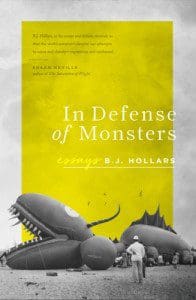

B.J. Hollars’ short essay collection, In Defense of Monsters (Bull City Press; 40 pages), opens on a world with no mysteries left. Now that seemingly every corner of the globe has been charted, and Google Earth allows one to zoom in on any coordinate one desires, the encroachment of human civilization on the natural world leaves us with little to explore. It wasn’t always the case: in the 20th century, even as horror spread across Europe and a racially divided America, the World’s Fairs promised a tomorrow full of discovery, and pulp novels sold readers on the idea of lost cities and forbidden jungles. Unsurprisingly, it was during this time that mythic figures such as Sasquatch and the Loch Ness Monster, which began as local rumors, developed into tourist attractions and subjects of international study. The Earth seemed like a place of wonder.

B.J. Hollars’ short essay collection, In Defense of Monsters (Bull City Press; 40 pages), opens on a world with no mysteries left. Now that seemingly every corner of the globe has been charted, and Google Earth allows one to zoom in on any coordinate one desires, the encroachment of human civilization on the natural world leaves us with little to explore. It wasn’t always the case: in the 20th century, even as horror spread across Europe and a racially divided America, the World’s Fairs promised a tomorrow full of discovery, and pulp novels sold readers on the idea of lost cities and forbidden jungles. Unsurprisingly, it was during this time that mythic figures such as Sasquatch and the Loch Ness Monster, which began as local rumors, developed into tourist attractions and subjects of international study. The Earth seemed like a place of wonder.

That sense has arguably since been stamped out, due in no small part to the scourge of war, the advance of technology, and a more skeptical populace. But in his essays, Hollars reminds us that “while three-fourths of Americans live in suburban and urban areas, only 2% of America is defined as such. The remaining 97% is considered rural.” Perhaps in those overgrown forest trails, lonely woods, and far-off mountain ranges, some domain still exists for these folklore creatures to flourish unseen by man. For Hollars, it’s not so important that scientists eventually prove the existence of a creature like Sasquatch (in fact, it’s immaterial), merely that our collective unconscious leave room for the possibility of their existence.

In Defense of Monsters wastes no time making its case: the opening essay “In Defense of Sasquatch” offers a convenient summary of the creature commonly referred to as Bigfoot—what would likely be a modern example of Gigantopithecus, an upright ape that lived some 300,000 years ago—and its many alleged sightings over the years. (Most astonishing is the fact that the Army Corps of Engineers recognized Sasquatch as a living creature in 1975’s Washington Environmental Atlas.) More interestingly, Hollars explores what such a creature might represent to our culture. He quotes nature scholar Joshua Blu Buhs, who writes in Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend that stories of Sasquatch have “long provided a way of thinking about what it means to be human: the contradictions, difficulties, limits, and the glorious wonder of it all.”

Considering that humanity has continued to re-contextualize the Hero’s Journey through stories and films about extraordinary beings and superheroes, it’s not difficult to imagine that the idea of Sasquatch, a creature caught somewhere between myth and reality, is somehow vital to our imagination, as though the continued possibility of witnessing something extra-human offers man humility or hope. In regards to those who are quick to try and invalidate sightings of Sasquatch, Hollars himself more pointedly asks, “What are we to dream of if there’s nothing left to dream?”

Hollars takes a more journalistic angle in the second essay in the collection, the somewhat misleadingly titled “Sasquatch in a Shell.” The piece isn’t about Bigfoot at all, but rather a 500-pound giant snapping turtle (with a shell the size of a dinner table) known as Oscar who was said to have resided in the waters of Churubusco, Indiana, shortly after World War II. Hollars paid a visit to Churubusco for the purposes of his essay, and his charming interactions with the “dedicated and good-hearted” people who reside there make for a fascinating human-interest story.

The quaint town—no bigger than a square mile, with a population of 1,800—momentarily transformed into a place of some hubbub in 1949 when a “gigantic turtle” dubbed the Beast of Busco was spotted in Fulk Lake by a local farmer and the town reverend. For a time, Churubusco found itself “in the eye of the world,” as Oscar the turtle generated coverage from the likes of LIFE Magazine and The Chicago Tribune. The turtle hysteria led to a booming tourist trade and local fundraisers, both of which continue to bring prosperity to the town to this day, though Oscar has never actually been captured or photographed—even after the property owners went so far as to drain the lake in search of proof.

The story of Oscar proves much like the town of Churubusco itself—simple yet earnest. In the words of local historian Chuck Mathieu, who befitting of a such a small community can trace his family history back to the founders of Churubusco: “I think that [Oscar] gave everyone something to hope for.” The town, then, becomes a microcosm for Hollars’ thesis that there is a spiritual benefit to a belief in the impossible. Oscar, although elusive as ever, continues to serve as a point of pride for the people of Churubusco, who have affectionately dubbed themselves Turtle Town U.S.A.

The essay collection concludes with “In Defense of Nessie,” an overview of the massive aquatic reptile known as the Loch Ness Monster. Nessie, as she is nicknamed, was first spotted in Scotland in 1933, a time when fascism and racial injustice were rampant across the globe, a point Hollars explicates in his conclusion, suggesting that the Nessie myth may have emerged to serve as a reminder that civilization wasn’t as advanced as man would like to believe.

While the essay may not be subtle about its point—and glosses over the perhaps more interesting notion that humanity may forcibly project these larger-than-life creatures into the world as a sort of counterbalance during times of great physic stress—Hollars does underscore one of the main ideas of the book: maybe the very reason there have been so few sightings and so little evidence of these animals is that they’ve witnessed what humanity has wrought and concluded that they must avoid us for their own survival. Or, as Hollars eloquently puts it, humanity’s message to beings such as Sasquatch or the Loch Ness over the years has been: “To avoid your own extinction, you must simply allow ours.”

For many readers, the only strike against In Defense of Monsters will be its length. At a scant 40 pages, Hollars’ collection makes for a slender tome; it’s a book that could be read over the course of a day’s lengthy commute. Regardless, Hollars’ ideas are rich and clearly expressed, and leave one in anticipation of the author’s further pursuit of the subject matter. Besides, it’s only fitting for a book about such ephemeral creatures to prove a fleeting read. While some might feel an inherent reluctance toward any book that tackles the subject of Sasquatch or the Loch Ness Monster with intellectual seriousness, it would be a shame if this keeps them from reading such fascinating insights into humanity’s fundamental need to believe in and search for the unknown.