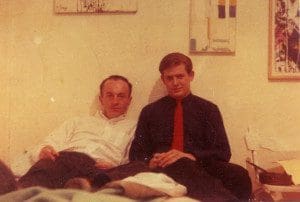

I was sad when I heard Bill Berkson died in June. I knew he’d been ill but didn’t know the details. But he always seemed to be the picture of a gentleman poet—by that, I don’t mean the stuffy, overly courtly, bow-tie beclad figure of an academic measuring his words in coffee spoons, of course. Or even exuding the quieter scent of class, though Bill clearly knew his way around the world of high society: His mother, Eleanor Lambert, was regarded as the doyenne of fashion publicity, and his father, Seymour Berkson, had been a high-ranking Hearst executive and for a time, publisher of the New York Journal-American.

From his early days, Bill was closely tied in with the New York School of Poetry, and his close friends and deep poetic influences included John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch and Frank O’Hara (he edited a posthumous collection of O’Hara’s work, In Memory of My Feelings, reprinted in 2005.)

But somehow he found himself moving out to the West Coast in 1970, living in Bolinas for a good while before returning to San Francisco and settling in Noe Valley. He taught in the California Poets in the Schools program and was also lecturer for many years at the San Francisco Institute of Art—he was ridiculously well versed in modern art, and knew most of the players personally. His gentle presence struck a notable contrast to the Beat and post-Beat decorum of the time. Bill was always an avant-gardist, who appreciated excessive expression, and behavior, but he walked his own road.

A collection of his letters—many of them in the form of questions and answers—with Bernadette Mayer, wonderfully titled, What’s Your Idea of A Good Time (Tuumba Press, $13.50), captures the ways in which he was able to bring out the best in others, including Mayer, a former New School student who has gone on to successfully find her own Muse.

They exchange gossip, literary likes and dislikes, summoning up an idyllic vision of the world in which nothing is forbidden, everything is possible, and judgment (for its own sake, not subjective points of view which are always encouraged) is irrelevant.

Some sample words from Bill, recently recited by Alli Warren at a lovely Memorial Tribute on Market Street last Saturday at the McRoskey Mattress Company.

Do you think of rich people as probably less virtuous?

What’s your idea of a good time?

Pleasure and glory—can you think of any other reasons for poetry to exist?’

Mayer responds:

Yes, still, to change the world! But when you put it that way, pleasure and glory, no, I can’t think of any others. Glories, someone once told me, is a word for the way the light breaks through clouds in shafts of it. Pleasure, purpose and glory, and for love. And lust for poetry!’

Bill was prolific, and I haven’t read as much of his work as I’d like (I fear some of it may be a bit beyond me). But like his contemporaries, on either coast or farther shores, his ear for the vernacular was unmatched, as in ”Signature Song,’’ included in his 2014 collection, Expect Delays (Coffee House Press):

Bunny Berigan first recorded “I Can’t Get Started”

with a small group that included Joe Bushkin, Cozy Cole,

and Artie Shaw in 1936.

Earlier that same year, the song,

written by Ira Gershwin and Vernon Duke,

and rendered as a duet pattern number by Bob Hope and Eve

Arden, made its debut on Broadway in The Ziegfield Follies.

By 1937, when Berigan re-recorded it in a big-band setting,

“I Can’t’’ had become his signature song,

even though, within a few months, Billie Holiday would record her

astonishing version, backed by Lester Young and the Basie Orchestra.

Lovers for a time, Lee Wiley and Berigan began appearing

together on Wiley’s fifteen-minute CBS radio spot,

Saturday Night Swing Club, in 1936.

Berigan died of alcoholism-related causes on June 2, 1942.

Although “I Can’t Get Started’’ is perfectly suited to Wiley’s

deep phrasing and succinct vibrato, she recorded the ballad only

once, informally, in 1945, during a New York theater engagement.

The Spanish Civil War started in 1936 and ended in 1939

with Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s forces entering Madrid.

“I’ve settled revolutions in Spain” goes Gershwin’s lyrics, just as odd.

There’s more to be said, and better, about Bill, by others. The tribute reading was filled with students, local art-world players, fellow poets, and friends. I even met a guy who ran a store in Noe Valley. Bill used to drop in and give him magazines.

Bill was quiet, but no one should mistake his gentle manner for weakness. He loved the world, even when he was angry with it, and wanted to share it with the seemingly countless people he also loved, and who loved him. He wore erudition and wit lightly, or to use one of his favorite words, with “ease.’’

In a video interview he did for his old prep school, he described his unique spot on the West Coast cultural landscape:

“It’s been a traditional thing since the late ’50s for artists of various kinds to flee the city. At a certain point they think it’s too demanding and they have to be somewhere quiet. Well, San Francisco is quiet, much more relaxed and less combative than New York but I like New York combativeness…

“There comes a time when I say, or something says, now’s the time to see what’s in this notebook. It’s not a job like any other, but it’s a job. In a way, it is a job like any other. It’s my job. It’s not weird.

“It’s a very bad sign if the so-called poet writes only when she’s inspired—inspiration is volatile gas. You usually see the inspiration in the first three lines, and then you’ve got to work. You can open Whitman at random and there’s this energy radiating off the page.

“All these writers that I know of have this built-in fear, which is then translated into procrastination. But, you know, I have good friends here. The long views are terrific. I’ve had the time to get the work done.”