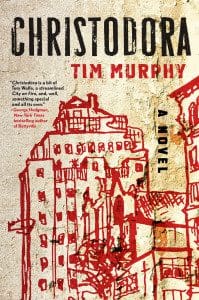

Tim Murphy’s latest novel, Christodora (432 pages; Grove Press), arrives in the middle of a cultural yearning for the seedier, more affordable, which is to say “idealized” Manhattan of yesteryear. Novels like Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire and television shows like Netflix’s The Get Down have embraced nostalgia for the cultural ferment of New York City in the ’70s and ’80s, its sense of an expansive and generative squalor. Superficially, Christodora bears this same stamp. Titled after a run-down East Village apartment complex two of Murphy’s protagonists buy for dirt cheap, the novel lovingly renders New York at its nadir. In the midst of that era’s decrepit neighborhoods, social upheavals, and myriad health crises, Christodora locates pleasure in the interstices of seemingly multiplying apocalypses. Whether it’s describing the dark ecstasy of a gay club or the contradictory pleasures of a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, the scenes here ripple with a so much life they prevent Murphy’s novel of the early years of the AIDS epidemic from being reduced to a 400-plus-page tome of human suffering. Covering six decades (even stretching into the 2020s), the novel deftly navigates an interconnected cast of Dickensian intricacy, as well, resulting is a convincingly rendered portrayal of the textures and rhythms of New York City, past and future.

Tim Murphy’s latest novel, Christodora (432 pages; Grove Press), arrives in the middle of a cultural yearning for the seedier, more affordable, which is to say “idealized” Manhattan of yesteryear. Novels like Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire and television shows like Netflix’s The Get Down have embraced nostalgia for the cultural ferment of New York City in the ’70s and ’80s, its sense of an expansive and generative squalor. Superficially, Christodora bears this same stamp. Titled after a run-down East Village apartment complex two of Murphy’s protagonists buy for dirt cheap, the novel lovingly renders New York at its nadir. In the midst of that era’s decrepit neighborhoods, social upheavals, and myriad health crises, Christodora locates pleasure in the interstices of seemingly multiplying apocalypses. Whether it’s describing the dark ecstasy of a gay club or the contradictory pleasures of a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, the scenes here ripple with a so much life they prevent Murphy’s novel of the early years of the AIDS epidemic from being reduced to a 400-plus-page tome of human suffering. Covering six decades (even stretching into the 2020s), the novel deftly navigates an interconnected cast of Dickensian intricacy, as well, resulting is a convincingly rendered portrayal of the textures and rhythms of New York City, past and future.

Murphy accomplishes this through a meticulous attention to detail, no aspect of which is too minute to escape description. Describing a gay club in the summer of 1989, he marshals every possible sensory detail— right down to noting an obscure house remix of Madonna’s hit “Like a Prayer”—into an impressive edifice of verisimilitude. This thickness of description makes it clear that lives have transpired here, not just tragic ends. Even in his characters’ lowest moments, Murphy’s writing exudes exuberance. In that same “Like a Prayer” scene, the AIDS sufferer-cum-activist Issy,is attending a drag show right after publicly admitting her illness, swarmed by her fellow activists. She feels shame for having contracted the disease, yes; but she’s also giddy, immersed in the moment of the times, a heady melding of incorporate terror and ecstasy. Accordingly, Murphy leaves us with this memory: “And now, oh God, the Shep Pettibone remix of the song of the summer: When you call my name, it’s like a little prayer. I’m down on my knees, I wanna take you there. The room screamed and collapsed into the pounding beats.”

This said, it’d be wrong to suggest Christodora isn’t concerned with the tragic, despite the. warm remembrances permeating the book. Murphy doesn’t look away from the macabre aspects of the early AIDS years, chronicling the enduring damage the epidemic wreaked on not just individuals, but upon entire communities. Starting with Jared and Millicent, the two upper-class white artists who’ve bought the Christodora, the novel widens its scope every few chapters, eventually encompassing their adopted son, Mateo, whose mysterious family history is a product of the pandemic; Hector, a once promising AIDS activist who has fallen on hard times; Issy, a young woman whose loneliness causes her to fall prey to the disease; and Drew, a drug-addicted writer who stumbles into Jared and Millicent’s lives only to transform them.

The novel’s power lies in this wide scope, in its ability to trace the devastating impact AIDS had on society’s varying levels and across generations. When Mateo’s anguish over not knowing his birth mother leads to a lifelong struggle with heroin, it becomes clear the epidemic’s effects aren’t relegated to a single death at a particular point in time. Rather, Murphy allows us to see how AIDS has rippled out from its locus to irrevocably affect the very fabric of society. At the novel’s midpoint, Hector and other activists gather in Vancouver to celebrate the discovery of an effective new medication. Around Hector, other activists behave as if the struggle is over, but he knows better. “Don’t talk about it like it’s the past tense, you know,” he advises a friend. “It’s not over.” Later that night, he smokes crystal meth with a prostitute in his hotel room. For him, the struggle has just begun.

The plague’s damage also dilates geographically, such that Christodora amounts to much more than a New York novel. In fact, about a third of the novel takes place in Los Angeles, where Drew decamps after kicking her cocaine addiction. Predictably, the city is the site of her rebirth, where she re-creates her identity and emerges from years of addiction as a best-selling memoirist. While she finds sobriety on the West Coast (or the “Left Coast,” as Murphy deems it), Los Angeles is the stage where Mateo’s struggle against his inherited past climaxes in a grim scene of drug abuse and sordid sex. It’s a sobering look into how people wrestle with personal demons, and a shocking evocation of how those demons rarely remain personal.

Christodora is not without its shortcomings. In particular, as Mateo’s L.A. experience makes clear, Murphy is a little too invested in making sure his characters’ story arcs intersect. These arcs come together in ways that sometimes seem silly, if not outright manipulative. They serve a didactic purpose, but the novel’s narrative often suffers because of them. Christodora’s primary plot twist is so obvious you’ll see it coming from a few hundred pages away, and perhaps feel cheated Murphy organized the entire novel’s narrative momentum around such a brazenly squalid event. But overall, Christodora is an accomplishment: a novel that is Victorian in its ambition to sketch the myriad ways in which a single disease impacts the whole of society.