The dedication page of Diane Seuss’s Four-Legged Girl (88 pages; Graywolf Press) reads: “For my people: the living and the dead.” But in this hypnagogic third collection, the margin between the living and the dead is “glory holed,” penetrated, and ultimately renounced. Seuss’s singular eye sees bodies everywhere, and her psychedelic syntax animates them. Spirea is “the color of entrails;” poppies sport a “testicular fur;” a blouse on the clothesline makes the speaker feel “as if [she]’d been skinned alive.” In these elegies, insensate matter becomes living human flesh.

The dedication page of Diane Seuss’s Four-Legged Girl (88 pages; Graywolf Press) reads: “For my people: the living and the dead.” But in this hypnagogic third collection, the margin between the living and the dead is “glory holed,” penetrated, and ultimately renounced. Seuss’s singular eye sees bodies everywhere, and her psychedelic syntax animates them. Spirea is “the color of entrails;” poppies sport a “testicular fur;” a blouse on the clothesline makes the speaker feel “as if [she]’d been skinned alive.” In these elegies, insensate matter becomes living human flesh.

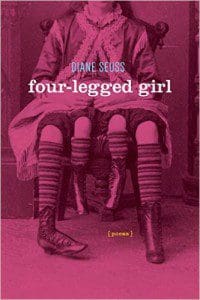

But the humans with whom Seuss is concerned are always already marginal: punks and addicts, convalescents and outsider artists. The first of the book’s five, vaguely chronological sections deals with the death of the speaker’s father, though his disembodied tumors haunt these pages long after his funeral in “As a child I ate and mourned.” Other recurrent characters include an ex-partner who dies of an overdose—referred to only as “my junkie”—and a two-headed, taxidermied lamb in a museum in the speaker’s hometown: “the precious freak who lives at the heart of me / still.” The book’s final poem is an ode to Myrtle Corbin, the eponymous four-legged girl, born in the late nineteenth century with two pairs of legs, two pelvises, and two sets of working reproductive organs. Seuss’s speaker, who frequently ponders her own body’s difference, with its “titanium leg and…wide caesarian scar,” makes idols of this motley cast of characters.

If these figures are ghosts, they are not the ectoplasmic holograms of common lore. In “People, the ghosts down in North-of-the-South aren’t see-through,” one of the many poems whose title doubles as its first line, Seuss explains how the undead operate in the Michigan of her childhood:

They want to steal

our valuables, mess shit up, drop a match and burn

down the house. I don’t know any other way to say it,

people. They walk right into our kitchens without being invited,

tracking mud, lifting the fish by the tail out of the fryer

and stuffing it in a cloth sack the color of a potato

just pulled out of the ground, and if there was a potato

pulled fresh out of the ground, they’d take that too.

These vandals and debauchers are Seuss’s people. She, too, “lived a life of smutty angst and restless kleptomania at the eye-shadow emporium.” She, too, was “scruffy, imperious, off-kilter,” luring home suitors just to sic her boyfriend on them. The most relentless specter in these poems is Seuss herself, in all her previous guises and iterations. In multiple poems, the speaker encounters another woman who gradually reveals herself to be Seuss at a younger age. (“Feasting on the younger versions of ourselves,” she writes, “that’s what we do.”) Like all of her metaphors, these apparitions are shockingly palpable, palpably shocking.

Like a sesquipedalian Philip Levine, Seuss draws on the range of unskilled labor she did as a young woman: “I’ve been a fetish-shop cashier, a fudge / worker in Vacationland, played Spidora / in the haunted house.… / Waxed the big / slide, Windexed the jukebox glass, supervised / the shooting gallery. Toilet worker at the sugar / factory.” Maybe it’s from these roles that Seuss derives her long and varied lexicon. Maybe it was in these roles that she refined her ability to shape-shift, to try on new epithets like the multi-hued fedoras in these poems. On the other hand, maybe that’s just how memory works: in quanta, in epochs. Sometimes, as if realizing she has indulged too much in self-mythology, Seuss’s speaker dials back: “Let’s not turn it into an epic.” Or, elsewhere, “Nostalgia is depression… / let’s toast to the present tense.”

Nowhere is Seuss’s synesthesia more apparent than in “I can’t listen to music, especially ‘lush life,’.” Her longest poem, “lush” is an eight-page requiem for her father and ex-partner that comprises the book’s entire middle section. By the time we arrive at “lush,” we are used to Seuss’s prolixity—which manifests often in inventories of complex horticultural nouns—so that this poem’s prosodic density is ultimately lulling and immersive. “Lush” binds the collection together: both physically, as the center (or “hub,” one of Seuss’s favorite words) of the volume, and thematically, as a collage of its major motifs. The poem is an extended riff on Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life,” whose plaintive lyrics Seuss uses as a template for her own autobiographical verses. By reprising memorable images from elsewhere in the book, Seuss makes “lush” feel familiar and resonant: there’s that funereal piano; there’s the absinthe; there are those derelict Michigan ghosts. It’s an impressive ekphrasis, consolidating the glittery despondency of Seuss’s poetry with that of Strayhorn’s jazz.

Maybe lush is the characterizing quality of this poetry. Lush as in overgrown, as in erotic, as in drunk. Lush as in botanical, both in content and florid execution. Even at their most mournful, Seuss’s poems are lush with triumph, ecstatic in spite of themselves at their own “screwy music.” Seuss slips sensuously between memories and metaphors with the droll fatalism of someone whose youth seems very far away. “Beauty is over,” she writes. But she knows it’s not. She knows it’s everywhere.

Sounds great. Definitely on my “to read” list.