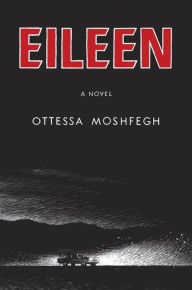

Eileen (260 Pages; Penguin Press), the new novel by Ottessa Moshfegh, examines the moment of change in a life marred by self-hate, servitude, and isolation. Eileen Dunlop is a twenty-four year-old woman who plays caretaker to her alcoholic father, for whom “the worst thing [Eileen] could commit … was to do anything for [her] own pleasure, anything outside of [her] own daughterly duties.” A gun toting retired cop, he is harassed by imagined “hooligans” day and night. The gun thus established in the first act, we await its discharge in the third. But in the meantime, Moshfegh ekes out the dark family history of the Dunlops and presents the inner workings of unsympathetic characters filled with loathing.

Eileen (260 Pages; Penguin Press), the new novel by Ottessa Moshfegh, examines the moment of change in a life marred by self-hate, servitude, and isolation. Eileen Dunlop is a twenty-four year-old woman who plays caretaker to her alcoholic father, for whom “the worst thing [Eileen] could commit … was to do anything for [her] own pleasure, anything outside of [her] own daughterly duties.” A gun toting retired cop, he is harassed by imagined “hooligans” day and night. The gun thus established in the first act, we await its discharge in the third. But in the meantime, Moshfegh ekes out the dark family history of the Dunlops and presents the inner workings of unsympathetic characters filled with loathing.

In Eileen, stalking, verbal abuse, criminal compliance, prison visitations, and pregnant silences masquerade as love. Eileen works at a boys’ prison, and in order to placate the restless visiting mothers, she hands out innocuous (and in fact meaningless) polls to “create the illusion that their lives and opinions were worthy of respect and curiosity.” She does this to “fend off her own hard feelings,” but what we are seeing is an unconscious attempt at compassion.

In Eileen’s retrospective telling of her younger years, we see how from early on she’s unaware of her capacity and her desire for humaneness and love—which she characterizes as leaping “from one person to another, like a flea” (hearkening John Donne’s “The Flea,” in which the metaphysical conceit is love, maidenhead, and union). Growing up in X-Ville, she understands friendship only as a useful tool for deterring brutality among the incarcerated youth, and community as just a police force that ignores and enables the once honorable, but increasingly unhinged “Father Dunlop.” Grounded by Eileen’s desire to run away from this world—and abandon her uncaring father—Moshfegh’s novel works as one person’s self-discovery in a pitiless environment, ultimately leading to a single transformative moment of violence.

Moshfegh propels her narrative through ever-increasing glimpses at Eileen’s future. (“If I’d had any idea that this would be the last Sunday I’d ever spend in X-ville, I might have spent it packing a suitcase… unbeknownst to me at the time, I would be gone by Christmas morning…I will do my best to narrate the events of my last days in X-ville.”) This acts to heighten the stakes, eventually bringing the reader to the moment that forces Eileen to take the plunge into a new life: the arrival of Rebecca, a new employee at the Moorehead prison for boys. Her introduction prompts the swiftly rising action that draws all previously established narrative threads into a taut through line.

Eileen is immediately smitten by the refined comportment of the beautiful, Ivy-League Rebecca, and she tries everything in her power to become friends with her. “I thought of Rebecca, whose arrival at Moorehead seemed like a sweet promise from God that my situation could improve. I was no longer alone.” Rebecca is kind to Eileen, and a conspiratorial bond eventually links them in friendship. Eileen comes to desperately depend on that bond, though, for her plan to escape X-ville to succeed. However, she seems temporarily stymied by her obsession with Rebecca, denying any existence of sexual attraction to her.

As our narrator approaches her moment of reckoning, one that will test her commitment to Rebecca (the story also unearths a crime that drives the enigmatic friend-as-savior to confront a person “more evil than [she] had counted on”), Eileen is given stewardship of her father’s gun, affording her a power capable of changing her future as she sees fit. With “Eileen,” Moshfegh expands on the skillful lyricism of her first novel, McGlue, revealing characters of depth and complexity that warrant our attention and compassion, asking of the reader to examine his own capacity for forgiving greatly imperfect people.