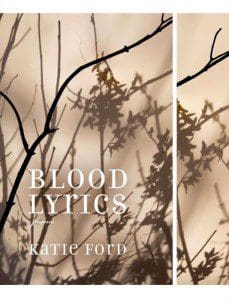

In her most recent book of poetry, which came out in late 2014, Katie Ford offers a raw and thoughtful look at the frailty of life, tracing the fragile line traversed alike by her premature infant daughter and the countless victims of war. Blood Lyrics (Graywolf Press, 62 pages) resembles a book of hymns, hauntingly personal, one piece coursing like blood into the next. Some of these poems ought to be delivered in a funereal whisper, others chanted to the rhythm of pumping hearts. Life and death are intimately connected, one necessitating the other.

In her most recent book of poetry, which came out in late 2014, Katie Ford offers a raw and thoughtful look at the frailty of life, tracing the fragile line traversed alike by her premature infant daughter and the countless victims of war. Blood Lyrics (Graywolf Press, 62 pages) resembles a book of hymns, hauntingly personal, one piece coursing like blood into the next. Some of these poems ought to be delivered in a funereal whisper, others chanted to the rhythm of pumping hearts. Life and death are intimately connected, one necessitating the other.

In the first poem, “A Spell,” Ford prepares us for the urgent tone that will carry us through to the end of this short, yet profound, collection. The urgency is that of a mother begging for the survival of her child. The images she offers in return are timeless—“lights,” “opal,” “bells,” “water,” “eyes,” “cotton,” “industry”—so as to emphasize the timelessness of motherly devotion. In this way she connects her own suffering to the mythic and historic, and she concludes the poem by offering up the ultimate sacrifice—her own blood: “and bleed me in the old, slow ways, / but do not take my child.”

Ford’s talent lays in her ability to use the personal as a lens through which to see the rest of the world. Her child’s health becomes the node around which her poetic language operates; words become meaningful primarily through their relationship to her daughter. For example, in “Of a Child Early Born,” money is used to measure weight rather than monetary wealth. “Our daughter weighs seven hundred dimes,” Ford writes, seeking out new ways of dwelling on the child’s meagerness. As we the readers come to accept these descriptions, we accept a new order of value: weight is the supreme wealth. Her daughter’s health usurps the old value systems dating even before the invention of the dime. Similarly, myths and religion lose their authority and didacticism; the Genesis story only serves to measure Ford’s own devotion to her daughter. In “Mathematician,” Ford writes, “I count her more dearly / than any genesis night.” She creates a parallel between God as creator of the world and a mother as creator of her daughter. Unlike God, however, Ford declares, “I need no sabbath.” Her devotion is not to her creator but to the being she has created.

The primary dialogue between personal and other in Blood Lyrics is generated by the very structure of the book, which is divided into two distinct sections. The first part, titled “Bloodline,” deals with motherhood and Ford’s infant’s struggle for life. The second, titled “Our Long War,” turns its gaze slightly outward toward the world’s continuous state of war. While the initial transition is perhaps a bit jarring for the reader, the effect is profound. Ford explains the catalyst for this work in the collection’s final poem “From the Nursery,” adjoined as a coda to the book: “When I looked up from her hospital crib / to see the wider world, could I help it / if I saw a war?” And indeed “war” takes on a myriad of meanings for Ford, from those pleasurable visits to the shooting range to the endless conflicts in the Middle East.

Infancy and war are not mere juxtapositions in this work, but rather filters for viewing one another. What new importance do the dangers of the world take on to a new mother fearful for her delicate child? And how do life’s feeble beginnings mirror its equally tenuous end? And perhaps most profound is Ford’s attention to the line each of us draws between personal and other and how this line shifts throughout life. Can a soldier’s death on the other side of the world ever affect us as profoundly as the wellbeing of our own child? The world seems to shrink to the size of the page in this collection, as Ford treats the strangers of war and her readers to the same intimate vocabulary as she does her own daughter.