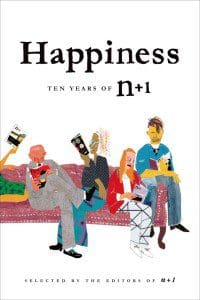

The collected pieces in Happiness: Ten Years of n+1 (369 pages; Faber and Faber) range from scintillating reflection, sharp economic or social analysis, realistic and depressing conclusions regarding the fate of the world economy, climate change, and the nature of humankind to the transformation of communication in the technological age, an extended satire on hypochondria and disease in America, and the perverted image of sexuality and portrayal of the self in media. Happiness is a conversation starter—easily accessible to any and all readers, yet nuanced enough to appeal to those who see what the current state of things really is.

The collected pieces in Happiness: Ten Years of n+1 (369 pages; Faber and Faber) range from scintillating reflection, sharp economic or social analysis, realistic and depressing conclusions regarding the fate of the world economy, climate change, and the nature of humankind to the transformation of communication in the technological age, an extended satire on hypochondria and disease in America, and the perverted image of sexuality and portrayal of the self in media. Happiness is a conversation starter—easily accessible to any and all readers, yet nuanced enough to appeal to those who see what the current state of things really is.

Mary Karr introduces the collection with a history of n+1, “a print and digital magazine of literature, culture, and politics, published three times yearly,” beginning with a breakfast meeting over bagels in 2003 with the then editors—Keith Gessen, Mark Greif, and Benjamin Kunkel. “Publishing itself was circling the drain,” Karr thought. But their vision was more substantial than happening into a cult following or perpetuating junk-journalism. “They wanted sprawling, ambitious articles you couldn’t squash into single sound-bites. They were the antivenin antithesis to the elevator pitch. They wanted to establish themselves as “curious thinkers, not pious knowers.” To take part in this contemporary thought is a delight, and n+1 has certainly achieved their vision in Happiness.

The collection is punctuated by editorial interludes that loosely organize the pieces by theme. They provide a semblance of structure—at least a logical cohesion to the succession of choices—but work well as stand-alone pieces, too. “Death Is Not the End,” for example, aims to connect pieces on an Isaac Babel convention (searching for the identity of a man who disappeared), one on Climate Change (the death of the Earth), an exposé on pornography and a reflection on sexuality.

The first of these interludes, “Happiness,” draws upon the history of happiness and its definition as an absence of turmoil—an absence of history and war. It recognizes a very conscious appropriation of the 18th century ideal of happiness— “the pursuit of happiness” and “the greatest happiness for the greatest number”—by the National Assembly and Continental Congress, and its pairing with capitalism, democracy, and freedom. Happiness then becomes an excuse to invade other lands, to torture others (as explored in “Torture and Parenting”), to exploit others’ sexual insecurities (“Afternoon of the Sex Children); this notion serves as a lens through which to discuss writing and unachievable knowledge (“Diana Abott: A Lesson”), and as a desirable result if we were to strip the theft of human value from our current economic system (“Gut-Level Legislation, or, Redistribution”).

Keith Gessen, in “Money,” explores his career as a freelance writer, journalist, author, and editor, after receiving a creative writing workshop position at an unnamed East Coast university. He posits, “There are four ways to survive as a writer in the United States in 2006: the university; journalism; odd jobs; and independent wealth. I have tried the first three. Each has its costs.” The specificity with which Gessen delves into his state of mind—his feelings of fraudulence as a teacher of fiction, his despair at having spent the $160,000 advance on his novel, landing him back at zero; his acceptance of what it takes to be a writer, which “[requires] you to make the decision, over and over and over again, to write. No one would care if you stopped doing it, even if they noticed. So there would be many moments in the future at which to decide to stop; or to decide not to stop, and to keep going”—is the same sort of specificity he asks of his students for in their stories. Gessen’s thinking on what it means to be a writer echoes Mary Karr’s thoughts on publishing. To support, champion, and produce the arts, one must be vigilant—be in conversation with the compelling issues of our time. As Happiness shows, n+1 is perpetuating and revitalizing this conversation.