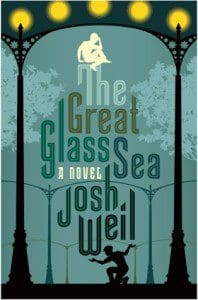

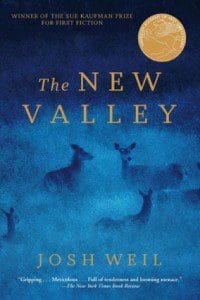

Josh Weil, author of the 2009 novella collection The New Valley (Grove Atlantic) and a National Book Foundation “5 under 35” Award recipient, saw his first novel, The Great Glass Sea (Grove Atlantic), published this summer. Moving away from the stark landscape of the Appalachian Mountains valley of his novellas, Weil’s The Great Glass Sea takes place in a near-future Russia, one where giant stretches of farmlands are covered by an ever-expanding greenhouse lit by space mirrors, keeping the crops beneath in perpetual daylight for the sake of productivity in Russia’s new capitalist scheme.

Josh Weil, author of the 2009 novella collection The New Valley (Grove Atlantic) and a National Book Foundation “5 under 35” Award recipient, saw his first novel, The Great Glass Sea (Grove Atlantic), published this summer. Moving away from the stark landscape of the Appalachian Mountains valley of his novellas, Weil’s The Great Glass Sea takes place in a near-future Russia, one where giant stretches of farmlands are covered by an ever-expanding greenhouse lit by space mirrors, keeping the crops beneath in perpetual daylight for the sake of productivity in Russia’s new capitalist scheme.

In this alienating and unforgiving setting, twin brothers Yarik and Dima, who were once inseparable in childhood, find themselves taking vastly differing paths in adulthood, growing increasingly distant as they navigate antithetical ideologies and lifestyles. Steeped in Russian folklore, the novel reminds the reader of the pressure of nostalgia on the present and the future, and draws a breathtaking picture of familial conflict, moving with ease between the haunting richness of the mythic and the piercing clearness of realism. We spoke to Weil via email about his work.

ZYZZYVA: To start, let’s talk about your writing process with The Great Glass Sea. What do you find yourself working toward in a novel that you don’t find yourself doing in a novella? Is it merely a question of length—a looking further and wider in your scope of the narrative, character development, etc.? Or is there some particular element in its craft that you believe can be achieved in one form and not the other?

Josh Weil: I feel very strongly that the experience of writing a novel is different from writing a novella and vastly different from writing a short story. All the forms offer their specific challenges, of course, and, with the novel, there were a couple difficult ones for me: First, how hard it is to hold the story—the whole dang thing—in your head at once; it’s nigh impossible. It’s very hard to know the story well enough (because of all the shifting and complicated threads) to get from the beginning to the end without going far astray.

Because I’m a writer who values the first draft tremendously (I feel that’s where the heart of the thing lays) rewriting is especially tough for me. Not revising or editing; I have no problem shaping what’s already there. (I love to tighten up a scene, pare out what’s not working, finesse a moment, hone a sentence.) But I feel like I’m losing something essential when I have to wholly rewrite a scene or even entire story arc. Still, the complexity of narrative (and its long arc) in a novel makes getting it generally right on a first draft nearly impossible.

Another challenge is simply how long it takes to get the thing into shape, especially when “the thing” happens to be a narratively complex 500-pager. It’s a matter of stamina. And of going half crazy with the way that each change, each edit, has ripple effects both forward and backward in the narrative, requiring ever-expanding revision. I went through six or seven major drafts of this novel over five or six years. I know that I worked every word of every sentence in the thing by the end. I also know that, by the end, I would have puked if I had to do another draft.

Writing novellas, at least for me, is pretty different. The story arc is just short enough for me to hold it in my head; I can see it from start to finish and see it’s pieces, and so, by the time I break through and start rolling, I can usually write it fairly quickly. And, often, the shape of the thing is pretty much in place by the time I get to my first readable draft. And that seldom changes. There’s a momentum that comes from writing like that—boom! The wall goes down and you go, go, go, letting the characters run, the story roll out, until you hit the end—that feels very honest and heart-driven and natural to me. And I think and hope that it transfers to the reader, that the experience of reading a novella can be deeply rewarding because of that: it’s a singular, immersive experience just long enough to fully sink the reader into the fictive world (as opposed to a short story that boots the reader out as soon as that magic happens) and yet short enough to be consumed in one sitting. But it’s a demanding form to write in, requiring a kind of intensity of focus (similar to a short story) over a sustained period that begins to have the depth and weight of a novel.

Z: How did your knowledge of Russia—its politics, history, and society—and your own time spent there influence you in creating the idea for the glass sea greenhouse and the zerkala space mirrors, and of course, their implications?

JW: Oh, I was hugely influenced by my own time there—both when I was a kid (I lived with a host family in the Soviet Union as an exchange student in 1991) and when I went back to research the novel in 2010. My earlier experience had been gestating in me ever since I was fourteen; I’d always known I’d write about it, and the world of this novel came directly from the world of my memories of that Russia long gone. It also came from the realities of contemporary Russia that I encountered when I went back. A lot of the physical detail came from that trip, but also the concerns of the book. I spent time with out-of-work loggers, stayed the night in what was essentially a peasant shack, hitch-hiked and camped in a little-traveled rural region, and lived with a high school teacher in a concrete apartment block—all of which allowed me to see so much of what I think of as the real Russia (as opposed to solely the moneyed world of much of Moscow, which most Americans are familiar with). I heard a lot of wistfulness for things that had gone away with “The Past Life” of the Soviet Union—a collapse of community, a crumbling of free time, family time, etc. People said things to me like, “We feel like animals, now,” meaning they were constantly having to struggle to make sure they could make ends meet. There was more to be had, but more ways to fail to have it, too. A lot of those kinds of concerns went into imagining the world of the novel and pressures the characters face.

Z: One might argue that similar questions of capitalism, over-the-top technology, worker productivity, and civil/social responsibility raised in your novel are relevant to America, too. What about Russia compelled you to write a novel that so intricately creates an alternate version of a reality that could, in some ways, also be envisioned in our own soil?

JW: In a very real way, the story set itself there. I was drawn to it first by the space mirrors — and they were something that Russia experimented with in the 1990s (pretty successfully, I might add). They were also the kind of thing (a bold — perhaps ridiculously so — idea pursued with the sense that mankind should conquer nature) that seemed particularly Russian. The Soviets had done things like trying to reverse the flow of rivers, or drilling a hole to the center of the earth. The idea of this green house the size of one of America’s Great Lakes (and ever expanding), of ridding a section of the world of nighttime by reflecting light down off satellites — these things seemed like uniquely Russian concepts. So that gets at some of the technology reasons. But, thematically, there was a reason I wanted to set it in Russia, too. While it’s true that the questions about capitalism and productivity and social/civil responsibility all could have been addressed by setting the story in America, setting it in Russia was a way of focusing those concerns, sharpening the lens — and looking at it from the outside in a way that, I think, allowed me (and, I hope, the reader) to see it anew. Because Russia went through such an upheaval from communism to capitalism, because it lost so much and gained so much, I felt I could deal with these issues in a more raw and immediate way.

Z: How does your background in film and writing screenplays influence the way you write scenes and dialogue in this novel?

JW: I think I learned more about the basics (of everything from structure to dialogue) from studying film and screenplays (and plays) than I did from studying literature. (I stress “the basics”; I learned more about the complexities and subtleties of writing fiction from reading fiction — and, of course, everything about voice). But I believe strongly in subtext as the driver of dialogue, and in characters always having to want something (often from each other) in a scene and that comes through in dialogue. I’ve learned to be comfortable with interiority, but my first instinct is to just let the scene play out, let the characters do stuff to each other, say stuff to each other — and there’s a real solidity and vibrancy to that. When you can’t go into a character’s thoughts (as in film) then you have to communicate those thoughts via dialogue and action, and if that dialogue and action is going to be dramatic and authentic it’s going to mostly be deflecting and covering and avoiding and skirting the specific truths that, in thought, we might get at more directly. That tension between the indirect dialogue and the sense of what it’s coming from is at the core of the way I write dialogue, and comes directly from film and playwriting.

Z: In your novel, the past clashes with the present and future both figuratively and formally. Scenes from the past are written into the “now” of the narrative as though woven in, time slipping seamlessly into the past and back again. What are your thoughts on creating narrative movement in this way?

JW: Don’t do it! No, seriously, it’s hard to do. So much of this novel does depend on resonance between past and present that I did find myself shifting back and forth between them, weaving them around each other, a lot. But it presents a narrative challenge, because pages that are spent on the past can complicate our understanding of a character and a situation, but can rarely move the actual plot forward. Still, because I think that readers (or at least this is how I work) are interested in questions—following questions, answering questions, unpacking questions — in a narrative, it can work by posing questions other than plot questions. If the past can raise a character question or a motivation question then it increases the dramatic tension and that is always good. But it does slow down the forward progress of the narrative. So, for me, it’s a matter of finding ways of balancing that out — the slowed narrative — with something else (say, a question that’s raised about how a character will deal with something emotionally) to make it worth it.

Z: On a similar note, why incorporate fables and the mythic into a story that takes place in an alternate near-future?

JW: Because I always saw the alternate near-future as a fable — not as science fiction. I don’t read science fiction; I’m not really interested in it. I do read magical realism; I do love fables. In this novel, I always thought of the light-eating mirrors and land-devouring greenhouse as fabled beasts, of a sort — just technological ones.

Z: In both The New Valley and The Great Glass Sea, you include illustrations. How do you see the relationship between the visual art the text it breaks up working?

Z: In both The New Valley and The Great Glass Sea, you include illustrations. How do you see the relationship between the visual art the text it breaks up working?

JW: When I read W.G. Sebald I feel that, through his illustrations and images, I’m experiencing the story on a different plane, a kind of different sensory immersion in the work than the words themselves can bring to me. And so, at core, I’m trying to do that with both these books. But that’s pretty much where the similarities end. In “Stillman Wing” (the illustrated middle novella in The New Valley) I was dealing with time in a way that was fluid and uncoupled from linear reality, so I wanted to break up sections in a way that was also fluid, that didn’t feel like as hard and clear a line as chapter break, a number, a title…etc. The images affect the reading experience both before you get to them, and after, and so I wanted that lingering to work on the story the in the slippery way that time does on the narrative. In The Great Glass Sea the goals were very different. wanted to communicate to the reader, clearly and from the start, that this was a fable-like world, that it wasn’t a hard-nosed realist depiction of Russia — and I felt the most subtle and yet also clear way to do that was with images that are inspired by the kinds of illustrations that accompany traditional Slavic folk tales. Those fables are also at the core of my feeling about Russia, and I can’t separate them from Ivan Bilibin’s famous illustrations. So I wanted to create something similar (or as close as I could get) with my novel.

I really enjoyed this, esp. …the experience of reading a novella can be deeply rewarding because of that: it’s a singular, immersive experience just long enough to fully sink the reader into the fictive world (as opposed to a short story that boots the reader out as soon as that magic happens) and yet short enough to be consumed in one sitting. But it’s a demanding form to write in, requiring a kind of intensity of focus (similar to a short story) over a sustained period that begins to have the depth and weight of a novel.” I love novellas and I’m glad to have these to look forward to!