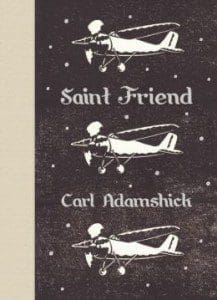

Saint Friend (64 pages; McSweeney’s Poetry Series), the newest collection by Carl Adamshick, is massive, not in length, as the collection clocks in at well under 70 pages, but in quality. The poems Adamshick presents us with are expansive thought projects. Even the shorter poems occupy a space that is difficult to comprehend—yet they are so readable, like all the poems here. The fact that Adamshick can write with such variance, that he can be in tune with society and with the incredible poets of the past and present, makes his work impressive and enjoyable.

Saint Friend (64 pages; McSweeney’s Poetry Series), the newest collection by Carl Adamshick, is massive, not in length, as the collection clocks in at well under 70 pages, but in quality. The poems Adamshick presents us with are expansive thought projects. Even the shorter poems occupy a space that is difficult to comprehend—yet they are so readable, like all the poems here. The fact that Adamshick can write with such variance, that he can be in tune with society and with the incredible poets of the past and present, makes his work impressive and enjoyable.

In the opening poem of the collection, “Layover,” the speaker is in an airport musing as “They keep paging Kenneth Koch.” He follows up with a beautiful existential thought that sprouts throughout the lengthy poem: “Someone should let the announcer know / he is dead, that there is no city he can go to, / that no one is expecting him.” It seems so simple; of course Kenneth Koch has nowhere to go. But Adamshick continues his line of thought: “I want to be paged once a day in an airport / somewhere on this earth, so people / will think I am just running late or lost.” The fear of mortality is perhaps the most relatable theme a poet can tap (that and love, which Adamshick touches on, too), but here the poet examines the anxiety surrounding our legacy, our curiosity about what people will say when we are gone.

Adamshick’s poems are also deeply concerned about our relationships with each other while we are alive. “My friends have moved away. They sleep / in places I’ve never been,” he writes in the poem from which the title derives, in which a friend, perhaps one that is far away, is being addressed. “These are the people we are. Saint Friend, / carry me when I am tired and carry yourself. / Let’s keep singing the songs we don’t live by / let’s meet tomorrow.” The writing moves from poignant clarity to tangential thought, showing that all can be included, that everything is connected in poetry and life. “Layover,” for example, is such a sprawling and captivating poem that an entire review could easily be written about it alone. And that is the beauty of Adamshick’s work. Each poem offers endless wisdom to share and discuss. Though only Adamshick’s second collection, Saint Friend seems like the work of a seasoned poet, the work being easily digestible but lingering long after reading.

“The Mathematician” lies in the middle of the collection and finds unlikely harmony between the worlds of logic and of lyric. The narrator relies on mathematics to negotiate the incongruences in his life. From the beginning, the poem feels raw and exposed, demonstrated especially as the man looks at his wife scarred from childbirth: “Naked. Unbelievably naked. I just stare.” The poem explores vulnerability in gaps of logic, and as it continues, the narrator moves closer to embracing the naked mortal body than irrefutable calculations: “Time itself is a decision. / My life has been in front of her every day…I know death is a friend / you can feel sorry with.” Aware of one of the most regrettable of calculations, the choices that come in wartime, Adamshick shifts time and place until the poem’s final tercet where he writes, “It’s been five weeks since Hiroshima. / I never wake her. / I don’t want this to ruin us.”

The final poem in Saint Friend is surprising, as it seems in many ways to act as a beginning. Titled “Happy Birthday,” the poem goes a step further from its relatable title in the first few lines: “The universe is infinite / and somehow expanding. / If you believe what people say / then you believe each of us is at its center.” Beginning with a comment on the selfishness of humanity that we all understand but do not often confront, Adamshick makes a bold move—leaving the readers questioning the importance of self-hood, and setting up the expectation that the poem will turn this notion around. The poem moves carefully into an intimate realm, leaving behind all those ideas about infinity and self-importance: “Our eyes are the only eyes we will ever have. / A ribbon of cloud darkens / above an ocean. / Everything is happening.” Here Adamshick shows us that one small event can be everything, and a single moment with another counts for much more than we think: “The moment is here, / it has always been here. / It is yours and beautiful in every direction.” The speaker is reaching out to another, over and over, in “Happy Birthday,” and the use of the second person is compelling, driving the poem forward, but also extending the longing: “I know you / and want to keep knowing you…I think your face must be different / than the one I see…I miss you.” The distance between the speaker and the you intensifies and shortens until we reach the end, slightly satisfied but also so far from where we started: “The day, / with all its chance and change, / with its nothing twice, / with no one other / than ourselves is coming. / Red star. Blue heart. / Happy Birthday.”

Adamshick, whose poems were published in ZYZZYVA No. 91, is a clever and thoughtful poet. He is aware of his place in the long lineage of poets before him, and given the high level of craft and intelligence of the poems in Saint Friend, he may someday be read among them.