Shortly after World War II, Minor White (1908-1976)—a photographer of some repute before the war—was in New York, freshly discharged from the Army intelligence corps, and speaking to Alfred Stieglitz in Stieglitz’s gallery, An American Place. In an often-quoted exchange between the two men, White, who felt the war had sapped some of his former verve, asked Stieglitz whether he could still take photographs. “Well, have you ever been in love?” Stieglitz said. White answered yes, and the elder artist explained, “Then you can be a photographer.” The conversation had a profound effect upon White. Indeed, whatever the immediate subject—the swirling figure of a tree trunk, the geological minutia of shoreline rocks—White’s photographs seem exceptionally intimate. Unknown to many at the time, however, was that as a gay man of that era, White struggled his entire life with love. Later, he would say his photographs were merely “reflecting the loneliness, the frustrations, the search for intimacy without embarrassment, and not much more. I am merely letting the camera visualize my inner-wishes—a lazy way of working.” It was Stieglitz who used to say, “When I photograph, I make love,” but that may have been far more true of White.

Shortly after World War II, Minor White (1908-1976)—a photographer of some repute before the war—was in New York, freshly discharged from the Army intelligence corps, and speaking to Alfred Stieglitz in Stieglitz’s gallery, An American Place. In an often-quoted exchange between the two men, White, who felt the war had sapped some of his former verve, asked Stieglitz whether he could still take photographs. “Well, have you ever been in love?” Stieglitz said. White answered yes, and the elder artist explained, “Then you can be a photographer.” The conversation had a profound effect upon White. Indeed, whatever the immediate subject—the swirling figure of a tree trunk, the geological minutia of shoreline rocks—White’s photographs seem exceptionally intimate. Unknown to many at the time, however, was that as a gay man of that era, White struggled his entire life with love. Later, he would say his photographs were merely “reflecting the loneliness, the frustrations, the search for intimacy without embarrassment, and not much more. I am merely letting the camera visualize my inner-wishes—a lazy way of working.” It was Stieglitz who used to say, “When I photograph, I make love,” but that may have been far more true of White.

Still, the photographer was correct to note elsewhere that “Sexual expression is only the foundation on which the cathedral is built.” So much is clear from the work reproduced in Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit (Getty Publications, 200 pages), which accompanies the current retrospective that opened July 8 at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. (It’s the first big retrospective of White’s work since 1989, and runs till October 9.) An unblinking, no-frills biographical essay by Paul Martineau, an associate curator of photography at the Getty, lucidly surveys White’s career as an artist, educator, and co-founding editor of Aperture. While he presents judicious commentary throughout the book, Martineau generally lets White’s life and work speak for themselves. He reveals White as an extremely lonely individual; a student of Catholicism, Christian mysticism, and Zen Buddhism; and an eccentric proto-hippie with, according to one photographer, “the persona of a guru,” who was worshiped by his pupils as a creative visionary. White was, writes Martineau, somebody who “believed that photography would help him to balance his natural tendency for introspection with his need to be engaged in the world.”

Despite his difficult personal life, White achieved fairly quick success as a photographer. After relocating from his native Minneapolis to Portland, Oregon, in 1937, White found work with the Oregon arm of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). He was paid to document the faded grandeur of soon-to-be demolished, 19th century buildings in Portland’s Front Street neighborhood. Some of the results are dark, moody, and romantic. In his free time, he also made productive excursions into Oregon’s countryside that resulted in work of impressive quality. One such photograph, Cabbage Hill, Oregon (1941), shows a ragged coil of barbed wire resting on a split-rail fence, signifying, as Martineau points out, “the hard physical labor required to live off the land” and “the redemption of humankind through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.” (White was being turned on to Catholicism by a friend at the time, and would be baptized by an army chaplain while serving in the military.) When New York’s Museum of Modern Art announced a call for submissions for a photography show on “the abstract ideal of freedom,” White submitted some of his pictures from the countryside, and three were accepted. He shared wall space with some of the best photographers of the day, such as Imogen Cunningham, André Kertész, Brett Weston, and Frederick Sommer. White was, in 1946, even tapped to become Edward Steichen’s assistant within MoMA’s Department of Photography, yet he declined the offer. Instead he began teaching with Ansel Adams at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), better known today as the San Francisco Art Institute.

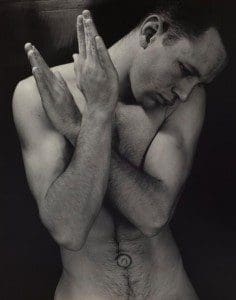

While in San Francisco, White produced a sequence of photographs called The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors (1948), which has never been published, or exhibited, as a whole before now. Why it wasn’t is clear enough: White’s sharply observed photographs consist of frank nude portraits of a young man named Tom Murphy, White’s student at CSFA. Illustrating a technical expertise he picked up from his friend and colleague Adams, White’s thirty-two pictures show Murphy, with his ruggedly angelic face and princely physique, performing in various situations, some with reference to Christian and ancient Greek art. The tension of the sequence is explored with great subtlety—“a cinema of stills” was how White aptly described such cycles—particularly with focused studies of Murphy’s expressive hands. And while modeled after Stieglitz’s erotic portraits of his wife, the painter Georgia O’Keeffe, the photographs depict a Christian theme of temptation and sin that is exclusively White’s. (According to Murphy, the two of them were never physically intimate.)

White viewed every photograph as a reflection of him—hence “mirrors” in the title—making this a very complex self-portrait. From Christian remorse to celebrations of the body electric, the cycle conveys a broad spectrum of contrasting tones and feelings, a brooding irresolution that puts the work among some of White’s finest. It was, however, also his most dangerous. “In the 1940s, it was illegal to exhibit or publish full-frontal male nudes, and any man who did so would effectively have outed himself as a homosexual,” explains Martineau. “The consequences for White would certainly have included losing his job as a teacher, his main source of income.”

The Temptation of St. Anthony remained a private project between the photographer and the model. When White was fired from CSFA in 1953, it was on account of a new director, Ernest Mundt, who had a new commercial vision for the school. White was forced to move to Rochester, New York, where he eventually obtained a position at the Rochester Institute of Technology. As Martineau points out, White was initially unmoved by his new surroundings, as “the pictorial possibilities of upstate New York were drab” in comparison to the expansive West. But in the years that followed, White produced some of his most recognizable work. Steely the Barb of Infinity (1960), which refers to a Baudelaire poem in its title, is a sustained examination of personal anguish, and one of White’s most melancholy sequences. Created in the wake of a dysfunctional relationship with a student, White’s abstracted pictures of water, snow, ice, and darkness are difficult to separate from his private life. His magnified pictures of crashing waves evoke the sort of uninhibited sexual release that eluded him. Unlike Ansel Adams (whose work can appear frigid and spectatorial), but like Edward Weston (whose work is sensual and rapt), White’s photographs typically approach natural phenomena not with distant veneration but with an immediate desire. Also, his ocean pictures may appear to share something with Georgia O’Keeffe’s magnified flower paintings—an artist who, along with White, had an interest in botany.

Without a doubt the most famous sequence White produced in upstate New York was The Sound of One Hand Clapping (1965). Martineau shares the widely held view that the sequence—whose title comes from the Zen koan “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”—represents White’s “chef-d’œuvre … the summation of his persistent search for a way to communicate ecstasy.” Beginning with an image of what appears to be “a Buddhist monk’s begging bowl,” but is really an old water tank, White’s transcendent sequence consists of some unprecedented photographs for the time. One memorable picture is the imperfectly titled Windowsill Daydreaming (1958), which shows a delicate orb of light and shadow beneath a window and evokes some inscrutable, disembodied presence. Sound of One Hand is certainly one of White’s most distinctive sequences for that reason, and is the culmination of his absorption of Stieglitz’s theory of equivalence, which opened up abstraction and metaphor to photography. “White pushed himself to do the impossible,” writes Martineau, “to make the invisible world of the spirit visible through photography.” It was a bold and unusual effort—probably one of the boldest and most unusual in photography at the time.

Using similar language in his book The Double Flame, Octavio Paz writes, “What the poem shows us we do not see with our carnal eyes but with the eyes of the spirit.” The poem allows us “to see the invisible.” It’s what White attempted to reveal, and indeed, as others have noted, his photography very much resembles poetry. White was a poet before a photographer and composed verses while in the military, which he eventually matched to pictures for a sequence called Amputations. (It was planned for exhibition at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor, but the museum was opposed to displaying the verses, and so White pulled out.) “Changing from verse to photography will only be a change of media, not the core,” White once remarked, and he was right. His pictures share with poetry a condensed communication, a command of detail, a hot attentiveness to the world, and a symbolic weight. (White followed Mallarmé’s directive to “Describe not the object itself, but the effect it produces.”) Images from his sequences have a common refrain and build much like words in a stanza. His photos often possess what Robert Frost identified as the stuff that begins poems: a lump in the throat, a lovesickness.

A case in point is Prospect Mill, Vicinity of Smethport, Pennsylvania (1957). Inconspicuous at first, the photograph depicts two trees in a small secluded clearing, crusted with patches of dry moss, surrounded everywhere by dead leaves and so close as to be united at the base. With its human scale perspective, the picture possesses a delicate intimacy that is short of astonishing. We seem to stumble into this clearing and immediately sense a narrative. (Indeed, the effect is similar to encountering William Carlos Williams’ description of a red wheelbarrow and some white chickens.) Why is this scene important? Why does it seem famliar? Like a poet thinking deeply of his readers, White shows at such times an intelligent consideration for his viewers. The photograph perfectly captures the meaning of his incisive remark that “many of my pictures hold out their hands … waiting to be fulfilled by a partner.” The trees here represent a pair of lovers forced into seclusion and secrecy, the kind White was forced into. In the Calamus poems, Walt Whitman similarly seeks out the “paths untrodden … for in this secluded spot I can respond as I would not dare elsewhere.” In the same set of poems, Whitman writes of a Louisiana oak tree that stands alone, “without a friend or a lover near”:

All alone stood it and the moss hung down from the

branches,

Without any companion it grew there uttering joyous

leaves of dark green,

And its look, rude, unbending, lusty, made me think of

myself,

But I wondered how it could utter joyous leaves standing

alone there without its friend near, for I knew I could

not…

Where Whitman broke off a twig from the oak as “a curious token” to remind him of manly love, White took photographs instead.