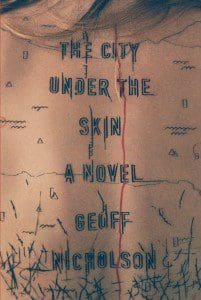

Geoff Nicholson’s newest novel, The City Under the Skin (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 272 pages), takes place in an unnamed city where women are kidnapped, then released back into the streets, now bearing poorly tattooed maps across their backs. Told from various points of view, the winding story follows a handful of characters—Wrobleski, a professional killer who begins to collect these tattooed women; Billy Moore, a criminal trying to turn his life around but who agrees to one more job; Zak, who happens to work at a map shop and is unwillingly dragged into the mystery, and Marilyn, who’s obsessed with finding out who’s collecting these women and why—until all the parties, and loose ends, arrive at an almost too tidy end.

Geoff Nicholson’s newest novel, The City Under the Skin (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 272 pages), takes place in an unnamed city where women are kidnapped, then released back into the streets, now bearing poorly tattooed maps across their backs. Told from various points of view, the winding story follows a handful of characters—Wrobleski, a professional killer who begins to collect these tattooed women; Billy Moore, a criminal trying to turn his life around but who agrees to one more job; Zak, who happens to work at a map shop and is unwillingly dragged into the mystery, and Marilyn, who’s obsessed with finding out who’s collecting these women and why—until all the parties, and loose ends, arrive at an almost too tidy end.

Throughout the novel, the idea of gentrification pops in and out of the story, which is a simple one: Ray McKinley, the owner of the map shop, is in favor of destroying old architecture in order to build new high rises. The mayor opposes him, so McKinley hires Wrobleski to get rid of people one by one until the other side eventually concedes. Though this subplot helps shape our sense of the city—a city that seems more or less run by thugs and criminals—the issue of gentrification isn’t explored any further and is near forgotten by the book’s end. Instead of deepening the novel, the theme of gentrification is used merely as a plot device, as a way of connecting the characters in sometimes overly coincidental ways. (For example, Wrobelski kills one of the character’s grandfathers, who happens to be the architect of the building McKinley specifically wants torn down. That character also winds up becoming one of the tattooed, and it seems she has the map of her grandfather’s murder and burial place inked on her back).

The City Under the Skin, however, does explore a very interesting idea: the purpose of a handmade map and the story it can tell. Typically, maps are only thought of as a means to get from Point A to Point B, as a way of telling you about where you are. But maps can also tell you about who created them. In the story, for example, a map shows where a rapist picked up his victims. The tattooed maps on the women contain a person’s story in the inked lines and dots and shapes. Maps can also be unintentionally and immediately dated upon creation. Cities are constantly changing—creating buildings, destroying buildings, adding new places, new monuments. When you map a place on paper you date it to that particular moment in time, and it becomes a reflection of what is already the past. And maps cannot include everything; they only pinpoint what their authors feel is most necessary.

The City Under the Skin starts off promising, but ultimately takes on more twists than it can handle.