Will Rogan’s solo show at the Berkeley Art Museum (BAM)—his first ever at a museum—includes two identical photographs titled Scout’s Ruler (2013). Deadpan, black-and-white, literal, the pieces are characteristic of Conceptual Art photography from the mid to late-1960s, when artists used cameras for strictly “objective” documentation, to convey only “factual” information. (Think Joseph Kosuth’s very literal photographs of shovels, chairs, lamps, and hammers.) But the one-foot ruler in Rogan’s photographs is not an impersonal object: It was created by the artist’s daughter, Scout, who has written the numerals 1-12 in reverse order. That subjective aura raises many questions about time, the show’s central theme. How can we “objectively” measure, or document, or even understand time? What “facts” or “information” can be shared about time, mortality, or dying? Or, to borrow from a poem by Franz Wright:

How does one go

about dying?

Who on earth

is going to teach me—

The world

is filled with people

who have never died.

An installment in BAM’s Matrix 253 contemporary art series (organized by curator Apsara DiQuinzio), Rogan’s show presents work that is frequently in conflict with what it is; irresolution and irony are key. It’s a visibly spare show as well, and appropriately so: Conceptualism’s concern with the dematerializing object (when the idea takes precedence over the thing) occurs here in real time because of time. There is a kind of deterioration in the art; it is both present and in the process of expiring. Its ephemerality can be felt. For Picture the Earth spinning in space (2014), for example, Rogan has taken a black-and-white photograph of a color photograph he exhibited a decade ago. The original, which shows a street sewer that has been painted over multiple times, is obscured and the meaning virtually lost. In the black-and-white print, the cracks in the pavement are more conspicuous, like metaphorical wrinkles on the face of his art. As he nears 40, Rogan, who lives and works in Albany, is not only thinking about time in relation to the way of all flesh, but also time in relation to the future, or lack thereof, of his art. That is not to say the tone here is entirely bleak. On the contrary, there is humor, heart, and even beauty.

In Erase (2014), the short silent film Rogan completed with his brother, an old-fashioned white hearse, parked in a somber landscape with hills and bare trees (reminiscent of a Caspar David Friedrich painting), blows up in slow motion. The film, which lasts for about six minutes, seems to oppose any rational approach to time, death, or mourning, as represented by the ceremonial hearse. In its embrace of chaos over order, in the visual seduction of the explosion, the film could be described as playing with allusions to Romanticism and the sublime (hence the Friedrichesque landscape). As the artist has said of the film, “To show the death of this object in a beautiful way is to suggest that beauty and tragedy are muddled, that inside everything is a kind of pragmatic operating system, and magical incomprehensible beauty.” Or, as the insurance executive said, “Death is the mother of beauty.” But it could be a mistake to take Erase completely seriously; there is something unmistakably comic about the gesture, too. It’s ironic the artist should give people some bang for their buck in the same show in which he reflects on the impermanence of his characteristically low-key art. That might explain why the film leaves you unsatisfied. You don’t survey the destruction; one minute the hearse is there, the next it’s clouded in smoke. The film calls to mind yet another statement of Wallace Stevens’: “The poem must resist the intelligence/Almost successfully.”

Even more memorable is Rogan’s artist book Broken Wands (2014), which may be read in the gallery but also purchased for $10 from the museum shop. For years the artist has collected back issues of the magician’s trade magazine M-U-M (Magic-Unity-Might). For Broken Wands, Rogan selected a number of the publication’s obituaries and reprinted them on inky black paper. It’s a very touching record of what you might call so many vanishing acts and grand finales. The glue that keeps the book together is Rogan’s curiosity and sympathy; you sense a little irony, but not much. Here, every human being performs a magical feat by simply being alive, and even the most outwardly modest existence has heroic dimensions. Consider the book’s opening entry, which concerns a Mr. Nym Hurt (Buddy) Johnson:

“He was a magician for over thirty years. During most of this period he performed from a wheel chair, since he was an arthritis patient. He had many magical friends throughout the country and, although he lived most of his life in Atlanta, several years ago he moved to Raleigh, North Carolina where he continued his magic and business. He was an expert watchmaker.”

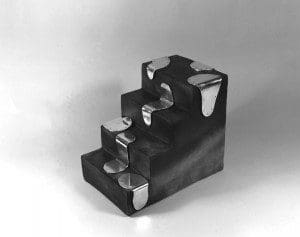

As an artist, Rogan clearly feels some affinity with the analogous profession of the magician. He relates to these dead in very meaningful ways. That is made doubly evident by the above obituary, for example, since it indicates the magician was an expert watchmaker (Rogan looked specifically for obituaries that mentioned clocks and photography). For Seven (2014), Rogan created a little minimalist sculpture from ceramic shaped like a staircase that begins and ends nowhere. Attached to the steps are brass melting clocks, or “soft watches,” that reference Salvador Dalí’s work. (It’s perhaps notable that Dalí lived in California for some time, and also authored a wild book called 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship.) Perhaps the allusion is specifically to The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1954), the painting in which Dalí visually breaks down the elements featured in the original The Persistence of Memory (1931). You sense that Rogan’s work is in a similar process of disintegration.

Roland Barthes, for whom every photograph represented “the return of the dead,” called cameras “clocks for seeing.” That may inform Rogan’s piece Negative (2014), a promotional plastic film camera that TIME Magazine sent to subscribers in the 1980s, which the artist has appropriated, reconfigured, and painted white. He’s also reversed the camera’s trademark “TIME” letters so they read backwards. Photography has been integral to Rogan’s practice over the years; and apropos of Barthes, this archaic device inevitably calls to mind the waning of film technology. With its color drained, it looks non-functional; with each passing day it becomes more and more obsolete. Once something that could freeze moments in time and call back the dead, this camera is itself frozen in time (another instance where Rogan’s art appears to be in decline). Moreover, because the camera comes from TIME Magazine, perhaps the piece also comments on the dematerialization of objects at the broader level of culture—tangible photographs replaced by digital files; print magazines replaced by Internet space. That is, perhaps Rogan’s disappearing art more or less reflects how technology continues to change objects, to cause them to vanish completely.

Will Rogan’s solo show runs till June 9 at the Berkeley Art Museum.