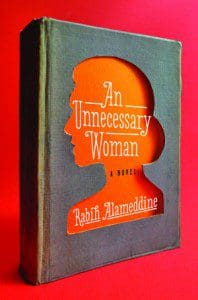

In his fifth book, An Unnecessary Woman (Grove Press, 304 pages), San Francisco author Rabih Alameddine examines the past and present life of a 72-year-old Lebanese divorcee and translator, Aaliyah, who has distanced herself from family and lost her only two friends. As she holes up in her spacious Beirut apartment and braces for bombs during the Lebanese Civil War or wanders the streets of her city decades later, Alameddine’s novel stays lodged within the confines of Aaliyah’s erudite mind, where she bounces effortlessly between Fernando Pessoa and Bruno Schultz. Literature is her only salve. For sticking with Aaliyah, the reader is rewarded with gorgeous moments of wonder and cranky humor that ripen a narrative and a life.

In his fifth book, An Unnecessary Woman (Grove Press, 304 pages), San Francisco author Rabih Alameddine examines the past and present life of a 72-year-old Lebanese divorcee and translator, Aaliyah, who has distanced herself from family and lost her only two friends. As she holes up in her spacious Beirut apartment and braces for bombs during the Lebanese Civil War or wanders the streets of her city decades later, Alameddine’s novel stays lodged within the confines of Aaliyah’s erudite mind, where she bounces effortlessly between Fernando Pessoa and Bruno Schultz. Literature is her only salve. For sticking with Aaliyah, the reader is rewarded with gorgeous moments of wonder and cranky humor that ripen a narrative and a life.

Alameddine’s protagonist wishes to remain invisible in a society that is happy to oblige her. Born to a mother who was soon widowed and then married her brother-in-law, Aaliyah is surrounded by belligerent half-brothers who consume all of her mother’s admiration. Aaliyah is married off to the first willing suitor. Ashamed of his own impotence, he divorces her, leaving her their apartment. Soon, her half-brothers are occasionally banging down Aaliyah’s door, demanding their inheritance to her home because they have children and wives. Aaliyah then locks out the world.

An Unnecessary Woman meditates on a question: What happens to life when it loses narrative possibility? Aaliyah refuses to change. She mulls over her past to retrace the points when her hope shrank. In her retelling, these memories, less significant in any other life, become jewels. She worked in a bookstore and nurtured a young, poor Palestinian employee who educated himself by sitting in the aisles with English novels. He grew up to become a militant, and during the war Aaliyah has passionate sex with him in exchange for a shower and a gun. With her intellectual richness, she mines these memories for deeper resonance: “My heart had momentarily found its pestle…Yeats once said, ‘The tragedy of sexual intercourse is the perpetual virginity of the soul.’” Her soul, however, has found its lovers in books.

Aside from literature, the city of Beirut serves as Aaliyah’s occasional companion. She wanders the streets as a philosophical tour guide who can spot the palimpsests of history — the place where a BMW crashed into a mule-drawn cart of cucumbers and tomatoes, “new Beirut crashing into old,” and a house reminiscent of Aaliyah herself. Surrounded by modern concrete houses, the crumbling sandstone abode is uncommon. “There are a few of these houses strewn here and there in the city, but none is as decrepit or as defeated as this one, and none as beautiful.” Like Aaliyah, age gives this house character and beauty even as wars and time trample it.

To ensure her invisibility, Aaliyah works as a translator for books she never intends to publish. Each year, in the pinnacle of her anticipation, she begins a new translation project by comparing the English and French versions and arriving at an Arabic compromise. As if it weren’t enough to be an overlooked translator, Aaliyah distances herself even further from the world by translating translations. She divides herself from people by other means, too, such as calling her perfectly friendly neighbors “witches.” If not for Aaliyah’s defenses, her neighbors could have provided her company for decades.

With his complete character study of a rare protagonist — an aging Middle Eastern woman —Alameddine challenges Hemingway head-on, even calling him out by name. “I always wonder what the point is with Hemingway…Critics and college boys insist that the apparent text is just the tip of the iceberg. More like the tip of an ice cube, if you ask me.” Wry and charming, hopeless and afraid, Aaliyah is the whole iceberg laid bare for us to see. Alameddine also challenges the idea of a novel that relies on epiphany: “There should be a new literary resolution: no more epiphanies. Enough. Have pity on readers who reach the end of a real-life conflict in confusion and don’t experience a false sense of temporary enlightenment.” Interestingly, though Aaliyah’s tale seems bleak, there does arrive a kind of epiphany. A seemingly catastrophic turn near the end of the book (an event involving Aaliyah’s precious collection of manuscripts) proves that Aaliyah’s life is not devoid of change after all—and that the solitary life of this elderly translator deserves a novel of its own.