At the heart of a dictatorship is the ability to control a country’s narrative, to embed an authoritative view into the personal, to elide difference in favor of a universal meta-story. Characters and subjective viewpoints judged “out of line” are relegated to the margins where they are placed in an ontological vacuum. Against this totalizing force, art finds potency in its ability to assail the putative objectivity of the dictatorship’s narrative, to create new stories, to offer the gaze of the individual free from hegemonic forces.

Soon after its inception, the sanctioned story of Augusto Pinochet’s brutal regime in Chile began to fray and tear. In February 1974, The Chicago Commission of Inquiry into the Status of Human Rights in Chile visited Santiago and issued a report whose principal findings showed that the “campaign of terror developed by the Junta seems to have assumed a systematic and organized character;” and the “number of persons detained as of January 20, 1974 exceeds 18,000,” with an estimated 18,000 having been detained in the six months prior to the report. Contemporary figures suggest that in the immediate wake of the coup, and across the austere and ruthless years Chile endured under the rule of Pinochet, more than 2,000 political adversaries were killed (of which 1,107 simply disappeared—the “desaparacidos”), 38,000 were tortured, and many more were exiled or fled as refugees[1].

If only as an oppressive force lurking just outside the frame of each photo, the narrative of Pinochet’s dictatorship stalks Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz’s work in her first solo exhibit in the United States, currently on exhibition at the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive till March 30. Composed in black-and-white and drawing from two bodies of work, La manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple) and Boxeadores (Boxers), Errázuriz’s exhibit tells with a testimonial and documentary reverence the poignant and personal stories of those whom the dictatorship attempted to ostracize and erase.

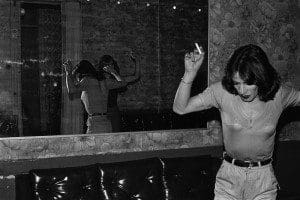

La manzana de Adán is comprised of photos taken between 1982 to 1987 when Errázuriz was photographing a group of male prostitutes and transvestites that lived and worked in various clandestine brothels in Santiago and Talca. In collaboration with the journalist Claudio Donoso, who transcribed their personal accounts, Errázuriz collated these photographs into a book-length photo essay that she published in 1990 after Pinochet left office. The texts and photos from the book, reproduced for the exhibition, present the construction of beauty and the plasticity of the body as the sight of narrative in dictatorship. In a chilling account, one woman recounts how the police “beat Nirka because she had breasts and they wanted to cut off her nipples. They cut off her eyelashes with scissors.” In a similarly horrifying anecdote, Pilar, one of the principal subjects in the La manzana de Adán exhibit, recounts the immediate days following the coup:

“We were with Leila in Valparaíso when the coup occurred and they took all of us to a ship moored in the port. They took us there blindfolded, in a van. For six days I was left there, piled up with the others, in the hold. The first thing the soldiers did was cut our hair; they pulled it by the roots and afterwards they pissed on us. They kept hitting us. They hung Tamara and Tila with a rope and made them spin turning them round and round. They threated to throw us overboard. They were some thirty of us homosexuals on board. We were released one by one.

They killed several of us during the coup. They killed Mariliz who was really pretty, just like Liz Taylor. This happened over Christmas. Her body was found in the Mapocho river, full of bayonet holes. At the Legal Medical Instituted we were told: ‘These are not knife wounds. They were made with bayonets.’”

Ethical discourse in Western art has been finely attuned to questions of exploitation and appropriation, focusing on and condemning how the gaze uses marginalized subjects for entertainment. While Errázuriz’s photos provide evidence of her marginalized subjects’ plight, the guiding aesthetic criteria, and the gaze through which the audience ultimately sees, is closer to that of the glamour magazine with its pictorial representation of the female nude or woman as sex-object. That Mariliz, the woman in Pilar’s anecdote, was killed perhaps because she was “really pretty” highlights the ways in which the regime-sanctioned aesthetic exerted power on the body. The erotic gaze, not merely a solipsistic encounter with the other, is a subversive force that pushes back against the totalizing violence. Errázuriz’s photos more than anything else present her subjects how they would like to be gazed upon: beautiful, sexually desirable, and human.

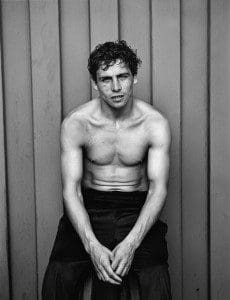

In Boxeadores (1987), Errázuriz turns her focus to another marginalized group: amateur neighborhood boxers. Errázuriz photographs the men, some with taped hands, slouched against a stool, some donned in gloves and headgear, isolated against a wall. There is a candid masculinity in many of the photos that engages with Errázuriz’s subtle dialogue of violence (Borges’ romanticization of Buenos Aires’ knife fighters seems an appropriate analogue). Rather than celebratory, the photos are undercut by an awareness of how powerless the violence and ceremony of boxing is against the new-fangled anarchical force of the military junta. The regalia that once gave these men a heroic air now seem anachronistic. The hero has been squarely placed in the horrors of modernism and is left ineffectual. Yet in documenting these boxers, Errázuriz crafts not only a story of the seeming futility of their skills, but an elegy for things past and no longer glinting in usefulness.

It has been more than twenty years since Pinochet left power and Errázuriz’s work was published. Yet these photographs remain an urgent counterpoint to the dictatorship’s narrative of nationalistic power and cultural and political homogeneity. For the stories constructed by Pinochet, perpetuated by active exclusion and disappearance, did not wither away when he was ousted in the referendum of 1990. Chilean society still strives against them as it seeks to understand the forces behind its current economic success and cultural-historical identity. To this end, the recent inauguration of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago was a landmark event, providing an institutional home for the many voices silenced during the seventeen years of Pinochet’s rule. These and other stories are of vital importance in Chile for at its simplest, the story of Chilean resistance was a question of how to remain human. It is a story that Errázuriz tells well.

[1] As cited in David Gallagher’s NYRB article, “Stories from Pinochet’s Prisons.” The citation is as follows “The figures were constructed over time in various documents, particularly the reports of the Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación of 1991 (National Commission of Truth and Reconciliation, at www.ddhh.gov.cl/ddhh_rettig.html) and the Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura of 2003 (National Commission of Political Imprisonment and Torture, at www.indh.cl/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Valech-1.pdf).”