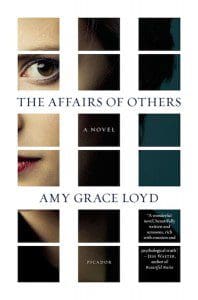

“American life asks us to engage in an act of triumphant recovery at all times or get out of the way,” notes Celia Cassill, the protagonist and narrator of Amy Grace Loyd’s first novel, The Affairs of Others (Picador, 272 pages). Celia has been all too happy “to get out of the way.” Since becoming a young widow, she has been hiding herself, her past, and her fears in plain sight as the landlady of a Brooklyn brownstone.

“American life asks us to engage in an act of triumphant recovery at all times or get out of the way,” notes Celia Cassill, the protagonist and narrator of Amy Grace Loyd’s first novel, The Affairs of Others (Picador, 272 pages). Celia has been all too happy “to get out of the way.” Since becoming a young widow, she has been hiding herself, her past, and her fears in plain sight as the landlady of a Brooklyn brownstone.

When an upstairs tenant is confronted with heartbreak, he pleads with Celia to allow him a sub-letter while he escapes to France. Celia reluctantly consents, and Hope, a woman slightly older than Celia, whisks into the building. “She was the sort who created intimacies when there were none,” remarks Celia upon first meeting her. Immediately, Hope is disrupting Celia’s perfectly controlled life. As the moans of Hope and her lover drift from her ceiling, Celia is set on a path that slowly strips away the emotional façade that’s protected her for years. With that unraveling comes a chaotic chain of events that cause one tenant to go missing, a husband to leave, and a psychotic man to threaten Celia.

While her tenants are gone for the day, Celia begins to let herself into their apartments. Through the landlord’s prying, Loyd shows us how each tenant harbors a secret of his or her own. As the reader starts to understand the damage hidden inside the walls of each home, and as the tension between Celia and Hope escalates, the novel becomes voyeuristic. The reader listens along to the sounds emanating from Hope’s apartment. Meanwhile, the other tenants are often peeking into the hallway to see Celia’s public breakdowns.

The wounds from Celia’s past eventually open more and more, until her story is revealed in the final, jolting account of her husband’s death. But in the midst of getting there, Celia finds a crutch in the most unlikely of characters—Hope. They develop an unexpected bond, one made believable because of Celia’s steadfast and understandably cynical narrative voice. As she gets to know Hope, Celia can say, “I was reminded that both of us had invested all our luck in whom we chose to love, to align our lives with.” She can take solace from that and from Hope’s insight. As Hope tells her: “We all are, darling. Animals. We’ve all done things we’re ashamed of, but survive.”

Loyd, who is an executive editor at Byliner, displays strong writing in both how she crafts Celia’s voice, which carries the novel through even the rockiest of her narrator’s experiences, and in the way she keeps contemporary Brooklyn and historic 9/11 delicately hanging in the background. Hope blames 9/11 for the end of her marriage, and the other characters often remember the ease with which life flowed before that September day. At the same time, Brooklyn is painted vividly through Loyd’s specific details. She abundantly evokes the city each time her characters step onto the street, rendering the confined space they inhabit near the brownstone and keeping the readers close to her embattled characters.