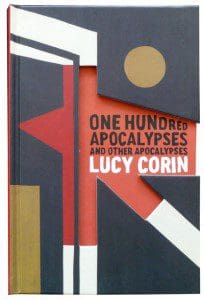

Lucy Corin has a gift for illuminating the dark and the unsettling through flashes of often absurdist humor, even of beauty. As the title of her new story collection, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses (McSweeney’s, 192 pages), suggests, Corin’s imagination is vast. In it, she nimbly shuttles us among a soldier encountering a witch, treasure-guarding dogs, and a girl he knew in high school; a pubescent girl agonizing over her coming-of-age rite, in which she selects a “madman” for her own; a high schooler obsessed with a neighborhood girl who disappears after California begins to burn unceasingly; and a squished slice of angel food cake that happens to represent the end of the world. The fractured leaps in setting, plot, and narrator mirror the chaos of Corin’s chosen theme, keeping the reader off balance.

Lucy Corin has a gift for illuminating the dark and the unsettling through flashes of often absurdist humor, even of beauty. As the title of her new story collection, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses (McSweeney’s, 192 pages), suggests, Corin’s imagination is vast. In it, she nimbly shuttles us among a soldier encountering a witch, treasure-guarding dogs, and a girl he knew in high school; a pubescent girl agonizing over her coming-of-age rite, in which she selects a “madman” for her own; a high schooler obsessed with a neighborhood girl who disappears after California begins to burn unceasingly; and a squished slice of angel food cake that happens to represent the end of the world. The fractured leaps in setting, plot, and narrator mirror the chaos of Corin’s chosen theme, keeping the reader off balance.

But Corin’s careful command of voice and tone gives us some grounding. The narrators’ conversational tone belies the fairy tale resonance to many of the stories, most especially “Eyes of Dogs,” based on Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Tinderbox,” which Corin retells in prodigious footnotes alongside her story. (The overt authorial self-consciousness of Corin’s footnotes was one element I found more distracting than effective in the collection.) Corin’s phrasing is often deceptively simple, lending her language a lyrical, folkloric feel. If her language is pared down, however, Corin’s command of surprising metaphor and imagery rivals Angela Carter’s. For example, here’s the witch in “Eyes of Dogs” advising the hapless soldier on how to use the little leather purse he’s just obtained:

“ ‘you put your mouth to its mouth […] you don’t call with your voice, but you call with your mind, and your tongue, into the darkness. You close your eyes and feel it there. You will know what to do. You will want what you want, and there it will be.’ He gave up making any sense of her, but he could tell she was making fun of him and making him feel lewd.”

Even fairly recognizable places and characters shimmer with this sense of the mythic. In ”Bluff,” a female motorcycle rider mounts her bike to “take on the world,” only to become stuck in the trench her wheels create in the plateau. She can’t push the bike out, so she “[rides] on, not knowing what else to do. Even now the trench walls rise.”

Through all of these disparate universes run consistent threads—primarily, the idea of the apocalypse. In the flash piece “Look Inside,” a woman searches out the lint in her belly button with her finger, a metaphor for crippling neuroticism and self-obsession. And toward the end of One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses, there’s the recurrence of the word “apocalypse” itself, cropping up in surprising associations. For example, there is a thief who “looked so familiar with all his fingers, the dark outfit, the apocalyptic two-by-two of his limbs”; a flasher’s coat, which opens to reveal “rows and rows of apocalypses [shining] along the satin lining”; there’s even a monster, the Apocalyptosaurus, “having the last sex on earth.” The repetition of the word dulls its impact, rendering it almost meaningless, and suggests Corin’s other thematic obsession—madness.

Corin is clearly intrigued by the unhitching of the mind from reality, and many of her narrators and characters are afflicted with some sort of madness (seen at greatest length in her story “Madmen”). As described in the flash piece “Metaphor,” madness “dams the river in your dick, hair over time in a drain. I know in the end it’s not like you are one thing and madness is another. It is a sleeping fist of your own stone bomb dick dam babies.” That opaquely mournful cry sums up the heavy atmosphere of disturbance in these stories. Whether an apocalypse is the destruction of the West Coast or the creeping awareness of a neurotic bellybutton-picking tic, Corin captures the uncomfortable moments of upheaval when the revelation occurs.