As a novelist, Adam Mansbach had been doing all right. His Angry Black White Boy (Broadway) was named a best book of 2005 by the San Francisco Chronicle, and The End of the Jews (Spiegel & Grau) won a 2008 California Book Award. And although Mansbach now considers it among the fond embarrassments of his youth, even his 2002 debut, Shackling Water (Anchor), was good enough for Library Journal to liken him to James Baldwin. So it seemed like the last thing Mansbach needed to do was swerve into new literary territory, particularly the limited realm of children’s books which are actually for adults and are premised on Facebook jokes. But he just couldn’t stop himself from writing Go the Fuck to Sleep (Akashic), and couldn’t believe it became a sensational bestseller.

As a novelist, Adam Mansbach had been doing all right. His Angry Black White Boy (Broadway) was named a best book of 2005 by the San Francisco Chronicle, and The End of the Jews (Spiegel & Grau) won a 2008 California Book Award. And although Mansbach now considers it among the fond embarrassments of his youth, even his 2002 debut, Shackling Water (Anchor), was good enough for Library Journal to liken him to James Baldwin. So it seemed like the last thing Mansbach needed to do was swerve into new literary territory, particularly the limited realm of children’s books which are actually for adults and are premised on Facebook jokes. But he just couldn’t stop himself from writing Go the Fuck to Sleep (Akashic), and couldn’t believe it became a sensational bestseller.

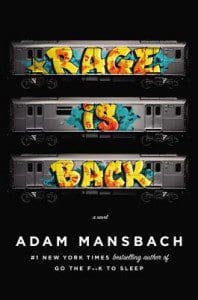

Nowadays, between taking up consequent opportunities (Sundance Screenwriters Lab fellowship, CBS sitcom pilot, Samuel L. Jackson-powered pro-Obama video), Mansbach still writes novels. His newest is Rage Is Back (Viking), summed up by its author with tender pride as “my magic-realist graffiti revenge novel.” As befits his musical affinities and his background as an MC, Mansbach has what you might call a hip-hop accent. Also, for a literary writer, he’s refreshingly unabashed about using profanity in conversation. On the phone a while ago, he chatted for a few minutes about his writing life.

ZYZZYVA: First, may we talk about your last book, and how its success affected you?

Adam Mansbach: It’s certainly affected my career in a lot of ways. It was a lark. It was never something I anticipated. The way the book sells continues to amaze me. It’s given me confidence in my own crazy tossed-off ideas. Not that every joke I make is going to lead to anything. Sometimes a thing can be very visceral, and just work. On a practical level it has opened up a lot of opportunities. I’d been getting a lot of “We love it, but we’re not going to buy it.” But now they can slap on “New York Times bestselling author,” and that helps. Right now I’m really focused on Rage is Back. So it’ll be interesting to see whether the million people who bought Go the Fuck To Sleep will get into this. I’m being realistic. This kind of thing doesn’t carry over. That’s a frustration of mine. We support the project; we don’t do such a good job of supporting the artist.

Z: But aren’t you often in demand as a lecturer these days?

AM: Yeah, and I’m usually there to talk about race or politics or the way that my work intersects with those things. When it’s announced that I also wrote Go the Fuck to Sleep, people look perplexed. It’s very hard as a writer not to get pigeonholed in some kind of way. For other audiences, I have to make them understand I’m not just some frustrated dad who wrote a book.

Z: Ah, and how are things going with your daughter?

AM: Aside from the sleep thing, which she’s thankfully past now, I’m shocked by the stuff that comes out of her mouth — by which I don’t mean profanity. The imagination is phenomenal. Watching her develop a love of words and stories is great. Having a kid makes you think about your values in a different way, and about what relationships you’ve had with your parents and your community. I see kids glued to the TV, and I don’t want that. For now we pretty much have a media free life! We read books, listen to music. She’s in a Waldorf school. The Bay Area is a good place to do that, very progressive. You can’t determine or legislate what they like, but you can put parameters. I can make sure she’s reading The Wizard of Oz and Alice in Wonderland, instead of some Barbie thing. Everybody who comes to my house has to read to her. She’s into Greek mythology. She likes the Arabian Nights. I’m a DJ and a record collector, and it’s funny that she understands music as something that comes on records. I take a little more pride than I should. She’s up on all the classic breakbeats. I try not to make her like a trained monkey. But she’s kind of a B-girl and I’m kind of proud of that.

Z: How did you get started as a writer?

AM: I can’t really remember a time when I wasn’t into language. My grandmother had a poetry column in the Boston Globe. My grandfather was a judge known for his eloquence; my father, a journalist. Words were a family stock-in-trade. The first writing I did was rhymes. And I had the good fortune of being 12 in 1988. My theory is that whatever you were listening to at that age makes a big difference. KRS-One and Public Enemy were really articulating a lot of what was interesting to me. I was a political kid. I grew up in Boston, which is a very segregated city. We had Metco, Boston’s 20-years-late solution to Brown vs. Board of Education, and hip-hop came to me from those kids coming out to my school from Dorchester and Roxbury. The rhyming, the dexterity, it was amazing. And there was no passively listening. If you wanted to be a part of hip-hop, you had to participate.

Z: Later on you were a roadie with the Elvin Jones Jazz Machine. Tell us about that.

AM: I got involved with Veen when I was 19 or 20. I was in college at Columbia, and I got the job as a roadie. And even though I was supposed to be in school, I would disappear whenever they were going somewhere too cool to resist. When I met him he was in his late 60s. He wasn’t a guy who talked a lot, but he surrounded himself with young musicians. It was great just to be in the presence of somebody so clear about the purpose of their art. Such devotion.

Z: Do you have an overall creative philosophy?

AM: Maybe about the approach. It’s not a switch you turn on and off. You try to stay open, always looking for material. But it’s an unconscious thing. If your senses are attuned enough, it’ll happen. I think everybody’s challenges are the same. It’s so much about finding the time to do the work. And keep doing it. When I look back at my first novel … well, I was really young. I wouldn’t imagine that I’d look back and be partially mortified by it. But maybe it’s like that with every book. I’m not a big fan of Malcolm Gladwell—I think he’s often full of shit—but I do like the 10,000 hours idea. Practice.

Z: What do you want us to know about Rage Is Back?

AM: Graffiti writers from the ’80s who stage a comeback in 2005. A cop who’s running for mayor. Some minor episodes of time travel. There may or may not be demons. It has some magic realist elements. And it’s narrated by a second generation hip-hop kid. This was fun because it’s going to succeed or fail on the voice. Either he tells the story in a way that brings you through all the craziness, or not.

Jonathan Kiefer is a writer in San Francisco.