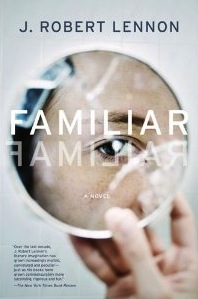

Somewhere on an Ohio interstate, where bored drivers can be counted on to whiz past the paranormal events happening in a middle-aged woman’s Honda, a crack in Elisa Brown’s windshield transports her from one brief, thirteen-page-long reality—of facts and blunt tragedy—to another. She finds her fingers gripping a different steering wheel, her toes jammed inside pumps instead of her usual sneakers, a husband who actually calls to see when she’ll arrive home, and, in place of her once bony frame, a plumper one that hasn’t suffered the death of her youngest son, Silas. J. Robert Lennon’s new novel, Familiar (Graywolf Press, 205 pages), follows this alternate Elisa as she navigates this disturbingly similar domain while attempting to make sense of the sudden shift.

Somewhere on an Ohio interstate, where bored drivers can be counted on to whiz past the paranormal events happening in a middle-aged woman’s Honda, a crack in Elisa Brown’s windshield transports her from one brief, thirteen-page-long reality—of facts and blunt tragedy—to another. She finds her fingers gripping a different steering wheel, her toes jammed inside pumps instead of her usual sneakers, a husband who actually calls to see when she’ll arrive home, and, in place of her once bony frame, a plumper one that hasn’t suffered the death of her youngest son, Silas. J. Robert Lennon’s new novel, Familiar (Graywolf Press, 205 pages), follows this alternate Elisa as she navigates this disturbingly similar domain while attempting to make sense of the sudden shift.

Elisa finds herself assimilating to this complacent, disappointingly tame version of herself. She practices the dry office work that her proudly scientific nature disdains. She agrees to see Amos, the couples’ counselor, whose wisdom has cemented her marriage with Derek.

At the same time, she conducts an uncertain resistance. To escape the extra bulk, Elisa resumes her old habit of walking to her job at the local college campus. She ventures into the physics department, making some tentative inquiries into her predicament. Inspired by a friendly PhD candidate in physics named Betsy, she sets out on a quest for a metaphysical explanation.

In her most disruptive act of rebellion, Elisa tries to reconnect with her estranged adult sons. In this world, she has renounced them for the sake of her marriage, a bond that, even in the absence of her children, heaves under some unidentifiable stress. Defying her husband, Elisa travels from New York to California. Silas, alive and healthy enough, is a video game programmer who spends his time harassing gamers on Internet forums. He welcomes his mother with hostility.

Elisa stalks Silas on the Internet and she masters “Mindcrime,” his most notable game. She seems always on the cusp of a discovery. Betsy points her toward William James, whose multiverse theory “was rebelling against the idea of predestination, of a universe that was a finished creation. A finished world. Where you have a role to play. And a God that cares about that role.” “Mindcrime” virtually manifests this figurative world of possible outcomes in video game form. Whoever has the controller in hand decides the fate of his or her on-screen persona.

The reader vicariously submits to the same kind of authorial control. We function as avatars in Lennon’s own virtual reality. He plugs and toggles away, moving us from one absurd conclusion to the next. We crave the theory that will tie it all together as much as Elisa does. Everything looks familiar, events and symbols appear to have a connection, but Elisa, and the reader, trapped within Elisa’s limited perception, can’t quite recognize it.

In “Familiar,” Lennon invites us into a false comfort, offering a story we think we can understand. He even mockingly has his protagonist question whether her situation falls into the genre of science fiction or psychological thriller. But the genre refuses classification, though Elisa’s universe looks like ours, where we expect science to satisfyingly explain most small-scale enigmas. Still, the plot hints (to our exasperation) at a solution.

The text cruelly exercises its protagonist’s ability to cope with the uncanny. Lennon plunges Elisa into a black hole. She returns to a world of only subtle differences—the foreboding kinds that creep under the skin and invade the limbs. Homely looks un-homely; Elisa looks like a badly pixilated version of herself. “The older you get, the more life seems like a tightening spiral of nostalgia and narcissism,” she muses, “and the actual palpable world recedes into insignificance, replaced by a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy.” Lennon invites us to wonder what copies have fooled us.