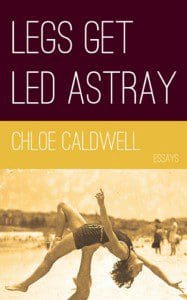

There’s a matter-of-factness about Chloe Caldwell’s sexually uninhibited, confessional essays, Legs Get Led Astray (Future Tense Books). “I am the type of person who will give anything to anyone I feel I could love, ” Caldwell writes at one point.

There’s a matter-of-factness about Chloe Caldwell’s sexually uninhibited, confessional essays, Legs Get Led Astray (Future Tense Books). “I am the type of person who will give anything to anyone I feel I could love, ” Caldwell writes at one point.

Caldwell is young—her work reflects that—but that is not to say the writing is immaterial or inchoate. It’s what I would call a greedy, ugly kind of “young,” the kind that makes you wonder if we are most alive, in a monstrous way, when we’re being hideous and awful. We spoke to her over Facebook about her frank and voracious book and how it explores horniness, a very large and very small thing that is as profound as it is shallow.

ZYZZYVA: In the essay “Yes to Carrots,” you write about a lover who lived with his girlfriend, and how the exciting tension in the relationship was between you (side project) and the other woman (lover’s girlfriend). The flips you did with that triangle were fresh. I loved how you constantly referred to her, shared with her and competed with her. There were signs of her everywhere and she took center stage. The lines I obsessed on were: “I was a guest on your toilet,” “I sucked your boyfriend’s cock religiously” and “Thoughts of him made me crazy. Thoughts of you made me calm.” Can you say more about how you gave your hungers free flight in your essays?

Chloe Caldwell: The things I was totally possessed by (the other woman, the man I loved, sex, my mother) were the easier pieces to write. They were written because I couldn’t not write them. “Yes To Carrots” flowed more naturally than any other essay in the book, because I was so worried about that situation all the time, and was writing it in my head constantly. I was journaling about the love triangle so often, taking notes on it. The sentences you mentioned were not me trying to be crude but just cutting to the truth, being realistic. It hurt to admit both of those things. Neither are things I was proud of. But for the sake of the essays, I had to push myself and write the uncomfortable things. For readers to relate to my writing on a deep level, I had to get a little uncomfortable. When I’m uncomfortable, I’m doing my job as a non-fiction writer.

Z: The way you addressed the other woman was vicious and honest and great. It was provocative and had a sense of greediness to it—which I loved. But what about the fact she was smarter than you—smarter than both of us—with that PhD in art history? What about the fact that she was more emotionally mature, certainly older, wiser, with bigger boobs and a “cool” attitude? What was it about you that made you compare yourself to her so intensely?

CC: I disagree with the statement that someone is smarter than us because they have a PhD in art history. That said, I think since I am listing things like that—the essay speaks for itself that I am comparing myself to her. We compare ourselves to other women all the time. It’s so human and that’s why people relate to the essay. You caught on to it. I just didn’t spell it out. I wanted some qualities that the other woman had—not her big boobs or her PhD, but I compared myself to her because she seemed emotionally stable and in a healthy relationship (well, that’s up for interpretation) and I wasn’t. And, I liked her lotion. On another note—she worked in the sex industry before she got the PhD. She was a dominatrix and also a stripper. Making her all the more appealing!

It’s interesting you talk about “greediness.” A reviewer recently called the essays “greedy,” and I think it’s impossibly dead-on.

Z: By “greed” I mean that in many of your essays, you’re a girl who is out for herself, unfazed by the ripple of her actions. And, now that I think of it, it’s the most compelling thread in your essays, and I related to that the most. It made me squirm. What I enjoyed about Legs Get Led Astray is the way you wandered from bed to bed and owned your pleasures throughout.Your pleasure contained a feminism that was joyous.

CC: I grew up in a very liberal, feminist household. Since I was born in 1986, the feminist way was very much paved for me. My brother could play with Barbies and I could play with trucks. My mom didn’t condemn the fact that I was masturbating on the couch. The thought that I couldn’t go do whatever I wanted—go to college/not go to college/get married/not get married/ was not on my mind. I feel lucky in that way.

Z: There have been a slew of wild women writers (who I strongly suspect regard themselves as feminists) who’ve been writing openly about hot, dirty, sex for ages. Without them, girls like us would never open our mouths in the first place. For instance, Kathy Acker, in her 1980 novel I Dreamt I Was a Nymphomaniac Imagining, wrote, “I’m 27 and I love to fuck.” Which brings me to you.

If I were in my twenties, Legs Get Led Astray would be in my backpack at all times, scribbled and underlined and thrashed. This book would be my The Terrible Girls, a collection of linked stories by Rebecca Brown from 1992. It had scenes like of a girl being fisted by another girl. I almost creamed my jeans while reading lines such as “And every crank you turn gets me wound up tighter, waiting, busting to spring.”

CC: My similar experience to that was with Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles. I remember reading a graphic sex scene, a balls-out, no bullshit sex scene, and that was the first time I’d read anything like it. I remember reading it aloud to a friend on the subway that same day. In Chelsea Girls she writes about buying drugs from the boys in the basement of the Strand, she writes about doing coke at her book party, she writes about smoking cigarettes on pavement and crying. I remember thinking “This is what I want to do.” I wanted to write about the little things in a big way.

Z: Eileen Myles has a profound casualness that is very admirable. For me it was her novel about insanity and her mom, Cool For You, that changed the way I thought about writing. I think you do capture tiny moments in big ways, like in your essay “The Trance Dance,” in which you attended a “New Age Camp” and considered the possibility of loving more than one person at once. I loved the scene where a bunch of teenage girls with retainers were dancing and crying and asking those questions. I loved how that essay ended pure and simple with “I swear my heart stopped.”

CC: Also, I don’t know if it’s too obvious to say that I am heavily influenced by Lidia Yuknavitch and Cheryl Strayed. I read The Chronology of Water last summer and highlighted it, and kept getting up to walk to the mirror with one hand on my stomach and one hand over my mouth. And Cheryl Strayed’s work is what I go to time and time again, when I want to study craft and cry at the same time.

Z: I knew it! We’re soaking in the same Cheryl Strayed/Lidia Yuknavitch hot tub. What other books were deeply influential for you?

CC: Another book and writer that showed me it was okay to go in the direction I wanted to go in was Break Up by Catherine Texier. It chronicles an ugly separation with her husband, but it’s written from the darkest perspective—she says the things that no one wants to admit and I think that book stayed with me more than I knew. I couldn’t believe she went to places she did in her subject matter and writing, and that it was non-fiction. She writes from a place of such anger, abandonment, and beautiful darkness.

When I was younger, I read a book by Elizabeth Berg called Joy School. There’s a scene in which the thirteen-year-old protagonist goes to her friend’s house, and her friend says to her: “I can vag fart.” I was shocked and disturbed and loved it. And there was Summer Sisters by Judy Blume, which was the most sexual thing I’d ever gotten my hands on at fifteen.

Z: You had mentioned in an email that some readers disliked your book because it lacked reflection evident in the work of more mature writers. I think it’s a sexist notion to expect female writers to be romantic or effusive. What I mean is, has anyone accused Raymond Carver of emotional stinginess? Had anyone said, “He just shows scenes and there’s not enough emotional accessibility?” I think that it’s a sexist expectation of women that publishers/readers demand certain qualities of female writers. Having said that, at times while reading your book I wanted a bit more interior juice. Was it a stylistic choice to exclude much reflection?

CC: I didn’t make a choice to exclude reflection. There’s that urgency and bluntness to Legs Get Led Astray because I wrote most of these essays while the situations were very close to me. If I were to re-write “Yes To Carrots” and “Hunger” in ten years I think they would have a different tone, possibly more regretful. Also, how fun would the book be if I ended each essay with the wise lesson I learned? I think that would be less honest than the way I wrote it. I’m 26 now, and I wrote the majority of the essays when I was 23 and 24, so they come off young because I was young, am young. Also, since I worked with a small press and not a major publisher, I wasn’t pressured to change my natural voice. A few weeks ago, my dad and I went to the show Once. I said at one point, “Why is this called Once?” He said, “Because once this happened.” Later he joked that my book could have been called This Happened. I love emotional intensity and sage wisdom, too. And to be frank—I do think there’s some of that in LGLA. I think that most, definitely not all, but most of the essays do get at a deeper meaning.

Z: There’s a touching moment in your essay “Sincere Sensation” in which you give away some precious wooden beads that belonged to your mother because, “I am the type of person who will give anything to anyone I feel I could love.” It made me wonder about the ways we abandon ourselves when faced with the possibility of love. It takes courage to write about powerlessness. Still, I kept asking myself, why? You seem to have great parents, a brother you actually like, and many men who want to fuck you.

CC: I don’t think my craving for love and approval is stronger than anyone else’s—I just think that I’m okay with acknowledging and admitting it. I’m profoundly interested in it. But the desire is one of the most universal things we have. It’s not that I’ve slept with many people; it’s that I was obsessed with the ones I did sleep with. As for why I was craving love and approval—I guess I can’t say. I did come from a happy and safe family, so I guess those things aren’t always all the way accountable for our fears or actions later in life.

One thought on “A Sexual Greed, Profound and Shallow: Q&A With Chloe Caldwell”