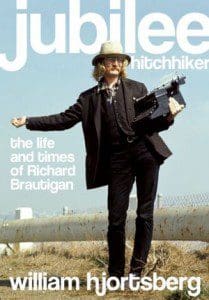

To simplify, Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan (Counterpoint; 880 pages), William Hjortsberg’s massive new biography of the late, once-iconic poet and novelist, can be roughly divided into three parts:

To simplify, Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan (Counterpoint; 880 pages), William Hjortsberg’s massive new biography of the late, once-iconic poet and novelist, can be roughly divided into three parts:

BUMMER. Brautigan’s childhood years, growing up poor and alienated in a dysfunctional family in the eternally drizzly Pacific Northwest. Highlights included the poet’s hospitalization—and treatment with electric shock—after throwing a rock into the local police station after a girl he had a crush on rejected him.

TRIPPY. Brautigan’s arrival in San Francisco, well ahead of the Summer of Love, whose spirit he briefly seemed to embody, and his immersion into the wild and crazy world of North Beach bohemia.

This section of the book, which comes as a welcome relief from the depression and Raymond Carver-esque solitude which preceded it, also serves as a spirited encapsulation of times and places that now seem as distant as pet rocks.

Despite a less than welcoming literary embrace from Allen Ginsberg, who called him “Frood’’ and a “neurotic creep,’’ perhaps in reaction to a competing literary visionary’s encroachment on his home turf, Brautigan found succor and support from North Beach legends of the time, including Jack Spicer, himself an exile from the main street of Beat bohemia, and Lew Welch, a tortured, twangy poet who ultimately walked away into the wild, though not before providing an entertaining alternative to academic exercises and overheated rhapsodies.

Somehow, somewhere, the tall dude with the floppy hat, blonde mustache and laconic demeanor, caught a wave. It may be impossible to really describe his impact if you never caught him in person.

I vividly remember seeing him loiter into Gino and Carlo’s incorrigibly unregenerate bar one evening. The place was jammed, Ginsberg was at the podium, and the gatekeeper moved to stop him at the front door, until Ginsberg, at this point reconciled to his competitor’s presence, finally shouted: “Let him in… the hippie …”

Words fail, ultimately, so here’s a couple of clips that give you a hint of Brautigan’s charm, in his prime:

Love Poem by Richard Brautigan

Or this sadly unprophetic view of a rosy technological future:

All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace

Or Brautigan’s daughter, Ianthe, reading from her father’s collection, Revenge of the Lawn:

Derided by some, then and now, as a Rod McKuen-esque poet of whimsy, Brautigan was more tough-minded than he is often given credit for. Re-reading “A Confederate General From Big Sur,’’ as I did recently, is a joyous experience. He makes surprising, deadpan connections; it’s like watching the trout he loved to describe leap from a stream.

Beating a retreat from his roommates amorous adventures, he writes: “I went downtown to see three movies in a Market Street flea palace. It was a bad habit of mine. From time to time I would get the desire to confuse my senses by watching large, flat people crawl across a huge piece of light, like worms in the intestinal track of a tornado.

“I would join the sailors who can’t get laid, the old people who make those theaters their solariums, the immobile visionaries, and the poor sick people who come there for the outpatient treatment of watching a pair of Lusitanian mammary glands kiss a set of Titanic capped teeth.’’

Brautigan was always more at home with the dispossessed and the disconsolate than in the bright lights, though he became no stranger to fame whores.

Even at the peak of his popularity in the ‘60s, he hung out with Emmett Grogan, the dyspeptic Digger who predicted the awful undoings that were to come. And later on, while drifting aimlessly on the outskirts of the poetry scene in Colorado, he kept his distance from the cult-like goings-on at the Naropa Institute, and kept a healthy skepticism for any institution that called itself the “Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics.’’

But the golden boy had some golden times. Hjortsberg’s description of a wild and crazy reading at Glide Memorial Church has the verisimilitude of one who’s been there:

“Scheduled to read his poetry in the Sanctuary at midnight, Richard determined to go down with the ship. By the time Brautigan arrived, total anarchy had taken hold. To the throb of a dozen conga drums, naked couples copulated on the altar while other nude crazies raced up and down the aisle on bicycles. A statue of Christ was splashed with the blood of an overeager celebrant who ‘got his head cracked during a scuffle.’ Thick clouds of incense hung in the high domed ceiling. A pair of frantic doves whirled overhead as dozens of chanting dancers stripped off each other’s clothing. Holding candles aloft, they pranced between the rows, dripping hot wax everywhere. A group of Hell’s Angels got it on in the back pews with a woman wearing a nun’s habit who called out, ‘More! More!’ One stoned individual sat cross-legged before the altar, coloring the carved marble tracery with a set of Magic Markers…

“… Richard told Keith [Abbott] all about it the next day. ‘Everything had gotten so crazy by that time…One of the Diggers had selected some speed freak as his representative. Between each speech by the church members, this guy would spew out a rap. It was like counterpoint. Everyone was trying to figure out some way to get the mob out of the church without calling the police and starting a riot.’ Brautigan recalled a [man] who seemed to be in a trance, repeating over and over to himself, ‘The one thing we agreed upon was no naked bodies on the altar and what did we get? Naked bodies on the altar.’ ’’

Like I said, trippy.

The bummers resumed, sadly, after Brautigan achieved the literary and commercial success that got him out of the cheap hotels he stayed in at Jessie Alley (named after a long-gone San Francisco courtesan).

His sojourn with the Montana literary and counter-culture set, including Thomas McGuane, Hjorstberg, Peter Fonda, and others, quickly deteriorated into a series of drunken revels, culminating in gunfire and food fights (once requiring a sprinkler to repair the damage to his living room). It may have seemed like a good idea at the time, but it was closer to Animal House than Yaddo—or anyone’s idea of a reasonable life.

He burned bridges, behaved badly, alienating a series of girlfriends and ex-wives, once close friends, and literary mentors, including his long-time agent.

It isn’t pretty reading, and it all seems so damned unnecessary, a willful waste of talent.

Hjorstberg clearly intends his 800-plus page tome as an homage to his long-time friend and neighbor. But like most such literary biographies, it’s unclear where tribute ends and tension begins. As the litany of sodden sediments and sentiments continue, it becomes clear Hjorstberg, by his own account a man of more moderate inclinations, has come not just to bury Brautigan, or to praise him, but to reap some kind of endurance award for having simply put up with the petulant poet for so long.

Nevertheless, he manages to convey Brautigan’s peculiar charm.

Before checking out of the “Big Hotel’’—at a personal, financial and literary dead-end—by shooting himself at his Bolinas home, Brautigan paid a visit to the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Asked if he wanted to see the grave of Jim Morrison, who Brautigan knew, the poet instead took a pilgrimage to the stone marked Apollinaire.

One likes to think that he would have been happier in the company of beautiful losers like the author of Alcools and Dada-istas like Max Jacob and Henri Michaux, than on his own fantastic journey into the mythic land of his Wild West origins, where he found fame, fortune, and ruin.

Anyway, as Hemingway, a writer Brautigan admired though they could not have been more dissimilar, might have said: Isn’t it pretty to think so? The road of excess may or may not lead to the palace of wisdom, but one has to salute the gallantry, however misbegotten, of the Confederate General’s last stand.

Paul Wilner is a San Francisco writer.