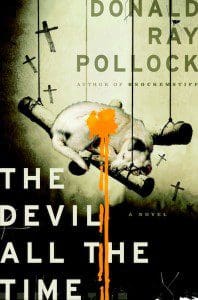

The major components of Donald Ray Pollock’s disquieting page-turner of a first novel, The Devil All the Time (Doubleday; 261 pages), are by themselves nothing special. There’s the novel’s crime fiction aspect: depraved criminals and less-than-innocent heroes on a bloody collision course. And the novel’s pivotal philosophical concern, one straight out of gothic fiction (as found in Cormac McCarthy and Flannery O’Connor): what does it mean to live in a godless universe full of incomprehension? Or in a world in which God seemingly doesn’t give a damn about what goes on down here?

The major components of Donald Ray Pollock’s disquieting page-turner of a first novel, The Devil All the Time (Doubleday; 261 pages), are by themselves nothing special. There’s the novel’s crime fiction aspect: depraved criminals and less-than-innocent heroes on a bloody collision course. And the novel’s pivotal philosophical concern, one straight out of gothic fiction (as found in Cormac McCarthy and Flannery O’Connor): what does it mean to live in a godless universe full of incomprehension? Or in a world in which God seemingly doesn’t give a damn about what goes on down here?

But Pollock, the critically-acclaimed author of the story collection Knockemstiff, melds his story to its idea in such a way that he elevates this graphic tale of predatory losers and hapless prey above the rot and stench (literal and figurative) of his characters’ lives. He combines them so successfully that the plot’s bullet-riddled climax comes to hinge, it seems, more on whether an inscrutable God exists than if one of two characters draws a better bead on the other. That he gets the reader to believe the stakes rest on whether any kind of divine grand scheme exists, on whether the world tilts indifferently toward evil or good, is a testament to his novel’s unrelenting mood of general helplessness and matter-of-fact barbarity.

Set in ‘50s and ‘60s southern Ohio and West Virginia, The Devil All the Time follows the tribulations of the young and the old, the well and the broken. As a boy, Arvin Russell loses in appalling fashion his quiet father and his beautiful mother. He winds up on the other side of the Ohio River in the care of his elderly uncle and devout grandmother, who is already raising a little girl whose homely young mother met a nauseating end—a death sickening for the ignorance that lays behind it. The forsaken girl’s father, a gaunt preacher who tests his faith by pouring a jar of poisonous spiders over his head, is on the lam with his cousin and partner, a fat, manipulative, wheelchair-bound guitar picker. Add a crooked Ohio sheriff and his slatternly younger sister—who takes “vacations” with her boiling failure of a husband, picking up male hitchhikers, cajoling them into taking dirty pictures, then photographing their transformation into corpses—and the players have been gathered for one pitiless if gripping clash.

Tempering all this awfulness into a compelling story is Pollock’s steely prose, the twang and humor of the dialogue, and the suppleness of his omniscient voice. The narration’s neutral point of view floats from character to character, letting us see pages later the person whose mind we’ve just been inhabiting through the eyes of somebody else. This narrative choice, executed over and over through slashing descriptions and crisp insights, rounds out the novel’s many characters to the point that Pollock can create a morsel of sympathy for even the most despicable of them. His villains may be horrific to behold, but they’re banal, too, and clearly lost. Their embrace of oblivion and corruption comes from losing feeling, if they ever had any, with what might be called the sacred of the world. It’s but one more harrowing shade of darkness to contemplate in The Devil All the Time as Pollock gooses along its many plots, building momentum to a final showdown that may or may not be part of something larger, something cosmic.

Donald Ray Pollock will be reading from The Devil All the Time at 7:30 p.m. on July 25 at Powell’s Books in Portland, Ore.