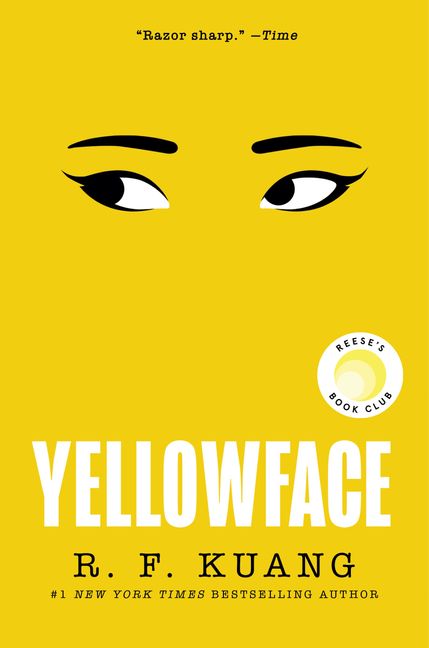

With her fifth novel, Yellowface (William Morrow; 323 pages), R.F. Kuang promised a departure from the speculative genre work of her fantasy Poppy Wars trilogy and science fiction Babel (2022), winner of the 2022 Nebula Award for Best Novel. Yellowface is a biting satire about the publishing industry, informed by Kuang’s own experience as a Chinese American writer who regularly tops bestseller lists. It follows the publication of protagonist June Hayward’s second novel, a historical drama titled The Last Front about Chinese laborers who fought for the Allied Forces in World War I. Kuang writes for a wide audience, and June’s first-person narration sets an energetic stride that the novel maintains for over three hundred pages.

“And you’re not… anything else?” a publicist asks June in an awkward meeting to strategize the book’s release.

“I am white,” June replies. “Are you saying we’ll get in trouble because I wrote this story and I’m white?”

That’s only half of the truth; at the outset of Yellowface, June steals the drafted novel from her friend Athena Liu. Athena is a literary darling and everything that June is not. The two met as Yale undergrads, but since then, Athena has become a bestseller while June’s debut languished in obscurity. Years of silent jealousy seethe within June as she gripes that Athena is “literally unbelievable.” Even though June’s narration is unreliable, Athena does come off as hyperbolic. She modeled for Prada, resembles “a Disney forest animal,” and is dubbed a “worthy successor to the likes of Amy Tan and Maxine Hong Kingston.” It’s difficult not to see Athena as a fictional version of Kuang—but Yellowface warns against assuming anything about the authors we read.

When Athena dies in a freak accident, June seizes the chance to grab an unfinished draft of The Last Front from her desk. She finishes it as a creative exercise, believing she is honoring Athena’s legacy. Soon, June feels ownership of the novel and sends it to her agent as solely her own work. June’s edits to Athena’s work are damaging; she casts a sympathetic view of the white characters in the history and alters its original bleak ending. After The Last Front sparks a bidding war and is tapped to become a bestseller, an entire publicity team decides how to promote June. They suggest she change her name to Juniper Song, issue a headshot that casts her as racially ambiguous, and forego a sensitivity reading of the novel. Kuang laments an industry in which selling the author is as important as selling the writing.

Kuang is unflinching in depicting the publishing paradox for writers of color. June believes that Athena has access to storytelling that white writers don’t: the diverse voice. “Diversity is what’s selling right now. Editors are hungry for marginalized voices,” June advises a young Korean American writer. Yet throughout the novel, it’s the exotic that publishing companies and Hollywood desire, not the people of these cultures. Writing about adversity and identity is coveted, but in limited, palatable dosed. “If anything, the system only turns critique into another way to profit,” Kuang said in an interview. Yellowface itself is a novel released by a major publishing company, hotly anticipated by booksellers who lauded its daring premise about cultural appropriation. I can’t help but wonder if it will drown cynically within “the system.”

Still, Kuang wades into complex territory and makes it legible to her readers. She often asks the big questions, albeit not very subtly. “Who has the right to write about suffering?” June wonders after confronting backlash when some of her readers realize she has no Asian ancestry.

Kuang need not look far from publishing for stimulus; cultural appropriation and claims of false ancestry abound in the academic community. High-profile cases include Rachel Dolezal, Andrea Smith, and most recently Elizabeth Hoover, an anthropologist at UC California Berkeley, who apologized in May for her false claims of Mohawk and Mi’kmaq descent. One email to June from an editorial assistant reads, “In this current climate, readers are bound to be suspicious of someone writing outside of their lane.”

Yellowface is at times more interested in this current climate than the story it’s telling. June and Athena become larger than themselves, no longer specific characters but representations of white privilege and silenced victim. They fluctuate between real and unbelievable, and besides June, no other living character is physically present for much of the book. It makes sense to know that Kuang began drafting Yellowface during the pandemic lockdowns of 2021. There is little interpersonal conflict at least until the end; crises unfold mostly though emails, text messages, social media updates, and blogs posts. Kuang keenly portrays the anarchy of the online realm, and the funny way publishing still clings to Twitter. Watching the unraveling reputational disaster that June brings down on herself has the addictive dread of doomscrolling late at night.

Kuang is often didactic in a book that reads like a modern parable. June’s hypocrisy and privilege are so ugly that it’s difficult to sympathize with her: she dons the image of an Asian American author when it suits her and sheds it to claim reverse racism when it backfires. Yellowface is at its best when characters are in the room together and the drama is personal. Flashbacks to Yale reveal Athena as a vulture for suffering, stealing from June’s experiences for her stories à la Bad Art Friend. Writers do the necessary work of looking at and expressing the horrors that others cannot fathom, June claims. But fiction does not vanish the real pain.

Although Yellowface is set up as a dialectic on cultural appropriation, it is difficult to become invested in Kuang’s commentary when it is distracted by the novel’s premise. Much of the book orbits a false center: the discourse around cultural appropriation assumes that June wrote The Last Front. But the novel is not merely June’s attempt to emulate the voice of a Chinese writer; it is the literal theft of the voice of a Chinese writer. In Yellowface, June’s plagiarism is the more severe and urgent crime while her success on the back of cultural appropriation is a kind of double damage. Her exploitation of Athena, not Chinese history, is the secret that destroys her psychologically and professionally. That the novel was about Chinese laborers at all was circumstantial—June happened to steal from Athena, who happened to be writing it. There is a confounding disconnect between Yellowface’s earnest attempt at a conversation about cultural appropriation and the trigger of the plagiarized manuscript. Whenever the reader might waver about June’s guilt in manipulating and profiting from Chinese history, they can be comforted by the moral backup argument: June stole the manuscript. Kuang’s prudence here feels uncertain and curtails the argument of the book. I wonder if Yellowface might have been sharper if June had written The Last Front by herself. Everyone knows that plagiarism is wrong. Throughout the novel, Kuang seems drawn to other more ambiguous, insidious types of stealing that artists practice and the trails of harm they leave. I wanted to follow her there but was derailed by a heist plot.