It all started with a haircut. Taking advantage of a slow Sunday, Luis W. Alvarez, a budding physicist, was at a barbershop on the campus of UC Berkeley, not far from where he worked at the university’s Radiation Laboratory. Sitting in the barber’s chair, he held that morning’s San Francisco Chronicle, dated January 29, 1939. In it was a wire report that said German chemists had bombarded uranium with neutrons—they had discovered nuclear fission.

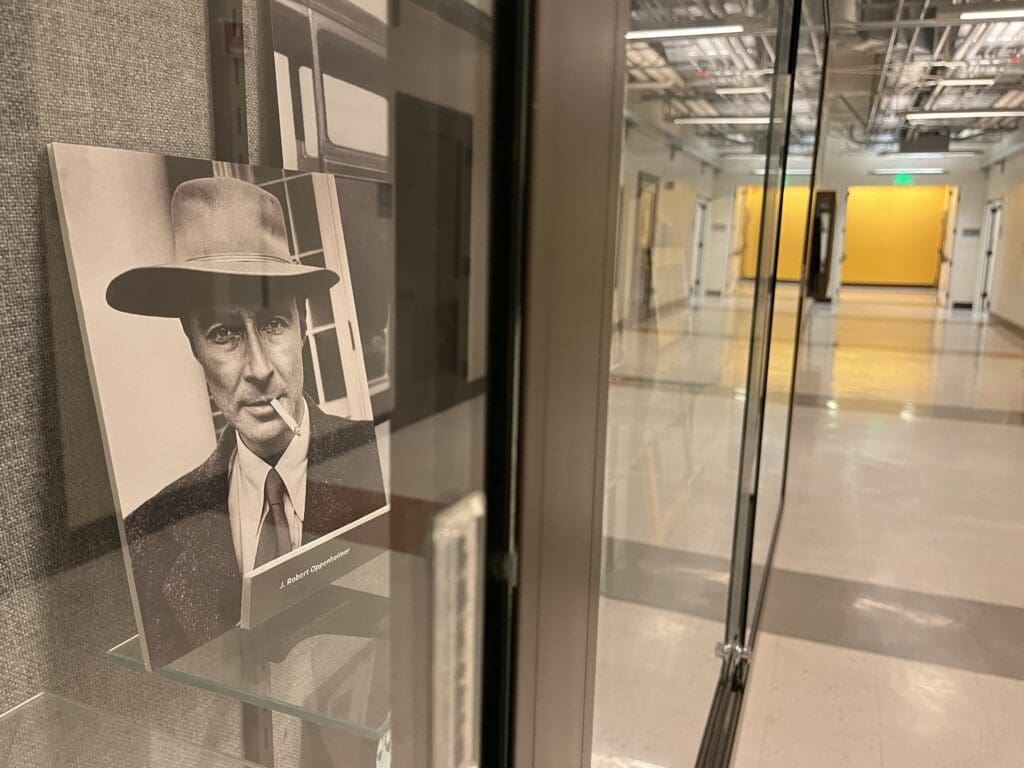

Alarmed by what he read, Alvarez “stopped the barber in mid-snip, and ran all the way to the Radiation Laboratory to spread the word.” In what was then known as LeConte Hall, the university’s physics building, Alvarez found fellow physicist Robert Oppenheimer. “That’s impossible,” the brilliant professor said when Alvarez informed him of what he had read. To demonstrate, Oppenheimer led Alvarez and others to a blackboard.

But it took Alvarez only one day to prove Oppenheimer was wrong. He repeated the Germans’ experiment, and Oppenheimer graciously accepted that fission was indeed possible. Within fifteen minutes, recalled Alvarez, Oppenheimer “not only agreed that the reaction was authentic but also speculated that in the process extra neutrons would boil off that could be used to split more uranium atoms and thereby generate power or make bombs. It was amazing to see how rapidly his mind worked.”

Shortly after, a graduate student walked into Oppenheimer’s office. There, on his blackboard, was “a drawing—a very bad, an execrable drawing—of a bomb.”

Six years later, the United States dropped two of these perfected bombs on Japan, the unprecedented and horrific culmination of a mammoth scientific undertaking—the Manhattan Project—that Oppenheimer oversaw, earning him the inescapable nickname the “father of the atomic bomb.”

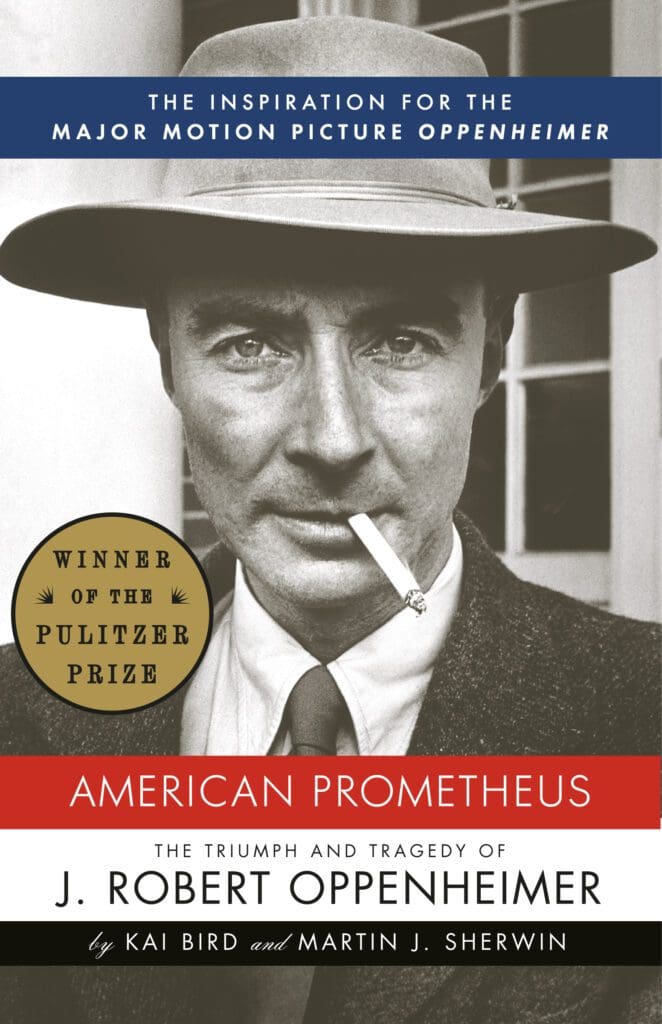

As Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin showed in their magnificent 2005 biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer—the Pulitzer Prize-winning book that is the basis of Oppenheimer, the new feature film directed by Christopher Nolan—much of Oppenheimer’s extraordinary life story is rooted in the Bay Area. The region is where the native New Yorker began his revolutionary research on the atomic bomb, and it is the area that fostered his progressive politics, nurturing a humanist worldview but also establishing a connection to Communist Party circles that would ultimately lead to his devastating humiliation at the hands of pernicious Washington forces out to ruin his reputation.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was born in 1904. He was raised privileged in a cultivated milieu; his father was a wealthy German-born textile importer, and his mother was a painter. As Bird and Sherwin describe it, he was a precocious youth, flourishing at Manhattan’s Ethical Culture School, the social justice-minded institution where the polymath devoured ancient texts and studied physics and chemistry in fifth grade. At age nine, he told a cousin, “Ask me a question in Latin and I will answer you in Greek.” A socially awkward student, shy and haughty, he earned his Harvard degree in three years. His youthful depression lifted, he said, after reading Marcel Proust’s À La Recherche du Temps Perdu during a walking tour of Corsica.

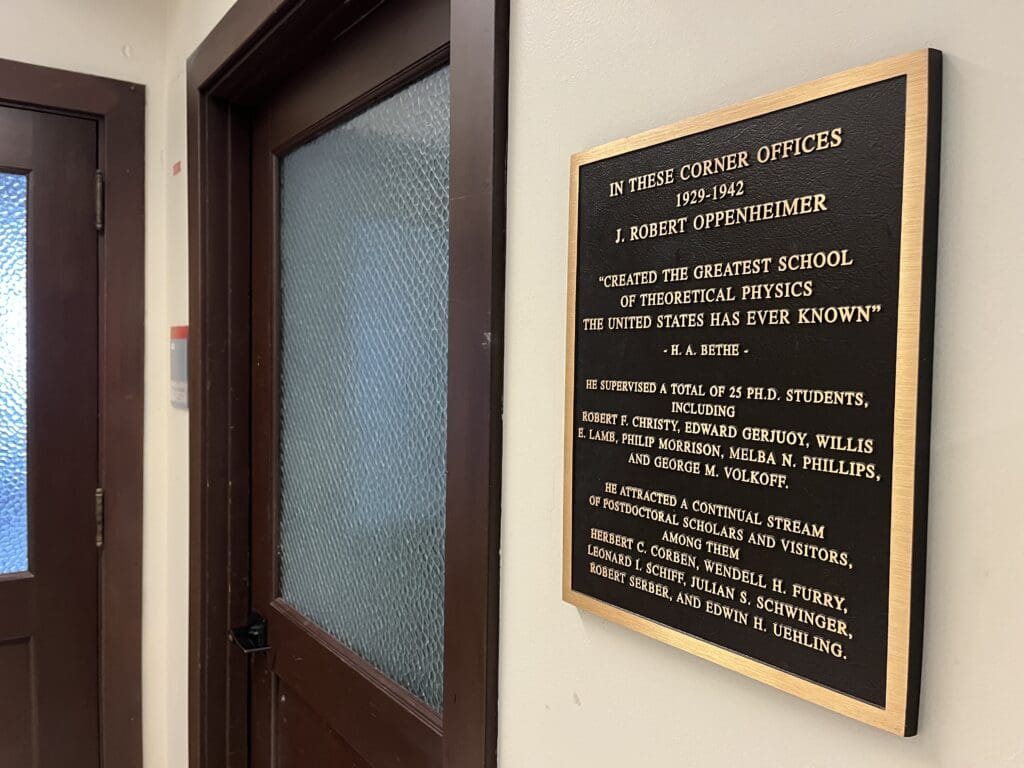

After teaching at Caltech in Pasadena, Oppenheimer settled in Berkeley in 1929. He was an assistant professor with a promising future. It was at UC Berkeley that the young man matured. An often-inscrutable lecturer who hummed the sound “nim-nim-nim” between drags on Chesterfields, he grew into a self-confident and witty figure who was lovingly called “Oppie” by his students. He regularly socialized with his bright acolytes, inviting them to the apartment he rented in a redwood house at 2665 Shasta Road, a place that had a view of San Francisco Bay, which he described as “the most beautiful harbor in the world.” For dinner, he served his guests “eggs à la Oppie,” flavored with Mexican chilies. Sometimes he played bartender, mixing his favorite drink, the martini.

The gregarious, blue-eyed scholar found that he was not without his charms. “He broke several hearts,” write Bird and Sherwin. Among the many women he dated was Estelle Caen, a piano prodigy and sister of the Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, and Melba Phillips, a graduate student he once took to Grizzly Peak for the view of the bay from the Berkeley hills. As soon as Phillips was bundled up in a blanket, Oppenheimer told her that he was going for a stroll. As if living up to the image of an absent-minded genius, Oppie forgot about his date; he walked to the Faculty Club, where, hours later, the police found him asleep. The incident landed him on the front page of the Chronicle, the first time he was featured in a news story: “Forgetful Prof Parks Girl, Takes Self Home.”

But it was Jean Tatlock who, in the words of a friend, was “Robert’s truest love.” The two met in 1936 at Shasta Road, where Oppenheimer’s landlord, Mary Ellen Washburn, was throwing a party. “Her beauty captivated Robert,” write Bird and Sherwin, “but so too did her shy melancholy.” Tatlock was a medical student at Stanford, yet she also devoted herself to political causes. As a dues-paying member of the Communist Party, she wrote for the Western Worker, a Party newspaper. Tatlock’s beliefs and activism helped fuel Oppenheimer’s social conscience—and would prompt questions about his patriotism during the Red Scare of the 1940s and ’50s. “I had had a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany,” Oppenheimer would later tell interrogators, explaining his political awakening. “I had relatives there [an aunt and several cousins], and was later to help in extricating them and bringing them to this country. I saw what the Depression was doing to my students. Often they could get no jobs, or jobs which were wholly inadequate. And through them, I began to understand how deeply political and economic events could affect men’s lives. I began to feel the need to participate more fully in the life of the community.”

Oppenheimer was never a member of the Communist Party, but he was an eager student. In 1936, on a three-day train journey to New York, the professor was likely the only passenger who had with him the three-volume, German-language edition of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital—all of which he supposedly read onboard. More significantly, Oppenheimer tapped into his substantial inherited wealth to donate to the Communist Party’s San Francisco branch, helping fund relief organizations fighting Spanish Civil War fascists. He also contributed money that went to migrant farm workers in California.

The Bay Area was a hotbed of labor activism at the time, and Oppenheimer gamely threw himself into the mix. He attended a longshoremen’s rally in San Francisco, inviting students to join him, and he donated his time to Local 349 of the East Bay Teachers’ Union, once addressing envelopes to union members until 2 a.m.

As a descendant of German Jews, Oppenheimer gave large amounts of money to support Jewish scientists who were fleeing Nazi Germany. In 1937, Oppenheimer met Dr. Siegfried Bernfeld, a Freudian analyst who had settled in San Francisco (where he would have little competition for his services, as there was but one other practicing analyst in the city). Oppenheimer was so taken by the newcomer that he copied his style, adopting what would become the physicist’s signature fashion statement, a porkpie hat.

Oppenheimer risked much for his activism; he feared that it might cost him his job. American Prometheus captures the tense political backdrop of the times, and the authors highlight how Oppenheimer faced opposition from colleagues, notably fellow physicist Ernest Lawrence, an “all-American” conservative (and future Nobel Prize winner) who was irked by Oppenheimer’s political engagement. “An extrovert,” the authors write about Lawrence, “he would use his natural affinity for salesmanship to promote his academic career.” Whereas Lawrence was invited into San Francisco’s elite Bohemian Club, “[t]he members of the Bohemian Club would never have thought to welcome Robert Oppenheimer; he was Jewish and too otherworldly.”

Even more active was Frank Oppenheimer, who joined his older brother out West, also pursuing a career in physics. A member of the Communist Party, Frank lived by his egalitarian ideals, marrying Jacquenette “Jackie” Quann, a Cal economics student who proudly identified as working-class. (Robert, prone to condescension, belittled her as “the waitress my brother has married.”) Frank fought for farmers’ and teachers’ rights, and he tried to desegregate Pasadena’s municipal swimming pool. His involvement with the CP would cost him his job at the University of Minnesota in 1949, and it was not until a decade later—after working as a cattle rancher in Colorado—that the blacklisted academic was able to revive his career in the sciences, ultimately founding the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

As strongly as they felt for each other, Oppenheimer and Tatlock’s relationship did not endure. The couple often fought, and Tatlock suffered from severe depression—it led to her suicide in 1944 at age twenty-nine. Tatlock’s father, John S.P. Tatlock, was a renowned Chaucer scholar at Cal, and he bestowed upon his daughter a love of literature. Her fondness for John Donne’s poetry in turn inspired her former lover. Oppenheimer drew from the English poet’s work—“Batter my heart, three-person’d God”—when giving a name to the first atomic bomb test: “Trinity.”

In 1939, after his relationship with Tatlock fell apart, Oppenheimer met his future wife at a garden party in Pasadena. Katherine “Kitty” Puening was married, but Oppenheimer’s friends welcomed the graduate student’s effervescence. “It may be scandalous,” said one, “but at least Kitty has humanized him.” Puening divorced her husband in 1940, and she and Oppenheimer were married the day the divorce was official. The new couple rented a house at 10 Kenilworth Court in the unincorporated community of Kensington, just north of Berkeley. They often held dinner parties. “Their bill for liquor,” said Kitty Oppenheimer, “was even higher than their bill for food.”

Like Tatlock, Kitty Oppenheimer was a member of the Communist Party. She grew up well-to-do (descended from Germany royalty, she bragged in her youth), and she gave her new husband a makeover of sorts, turning him on to pricey suits and tweed jackets. Oppie, for his part, got rid of his old Chrysler coupe, buying Kitty a new Cadillac. Mixing business and pleasure, they named the car “Bombsight.”

Within a year, the Oppenheimers were parents. Peter was born in 1941, followed in 1944 by his sister, Katherine “Toni.” Shortly after Peter’s birth, the family settled into a nearby house on a quiet cul-de-sac in Kensington, at 1 Eagle Hill Road. The house was theirs for almost a decade. A lovely Spanish-style villa, it had a commanding view of the Bay like Oppie’s old place in Berkeley. The couple paid $22,500 for it, equivalent to—yes, times have changed—less than half a million dollars today.

That Kensington home came to be the site of a short conversation that would haunt Oppenheimer years later. After being named the director of the Manhattan Project, in 1942, he and Kitty were hosting their good friends Barbara and Haakon Chevalier, the latter a French literature professor at Berkeley. Chevalier joined Oppenheimer in the kitchen as Oppie made martinis before dinner. He told Oppenheimer that George Eltenton, a physicist they knew at the Shell Oil Company, had solicited Chevalier, as Bird and Sherwin write, “to ask his friend Oppenheimer to pass information about his scientific work to a diplomat Eltenton knew in the Soviet consulate in San Francisco.”

Oppenheimer fiercely rejected the treasonous scheme, he said, and the two men dropped the subject. However, the conversation—and Oppenheimer’s subsequent contradictory account of it—ballooned into “the Chevalier affair,” an incident that would be used to bolster a case against him. After a 1954 investigation and hearing conducted amid the anti-Communist hysteria of the time, the government decided to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance; the physicist felt it to be a slap in the face to someone who had given so much to his country.

Many in the government had long been wary of Oppenheimer, even though he had been entrusted with directing the research and design of the atomic bomb. His house was bugged, as was his office in LeConte Hall. The FBI learned that Robert and Frank Oppenheimer had donated money to the Communist Party—after agents broke into the Party’s offices in San Francisco. Orders to search for anything that could be used against Oppenheimer came from no less an authority than J. Edgar Hoover, the notorious FBI director who targeted many on the Left.

By the time he began working on the Manhattan Project, however, Oppenheimer had curtailed his activism. The allure of communism had faded, as it had for many who soured on the Soviet Union. Also, given the prominence of his crucial new position—overseeing a monumental engineering project in Los Alamos, New Mexico—Oppenheimer understandably wanted to be seen as beyond reproach. Driven by his desire to build an atomic bomb before the Germans, Oppenheimer, wishing to become a lieutenant colonel, went so far as to prove his allegiance to his country by getting a physical at the Presidio Army base in San Francisco. He failed. Weighing only 128 pounds and suffering from a “chronic cough” (throat cancer would kill him in 1967), Oppenheimer was told he was “permanently incapacitated for active service.”

At Los Alamos, following VE Day, Oppenheimer learned to his disillusionment that his work on a bomb would instead target Japan. And he would not know that before the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan had been contemplating surrender. After the bombings, Oppenheimer sank into depression. His distress only grew after the war.

His work done at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer imagined returning to California. “I have a sense of belonging there which I will probably not get over,” he wrote at the time. He and Lawrence, his old friend, were clashing, however, and a new position presented itself elsewhere: he accepted an offer to direct the esteemed Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he joined, among others, Albert Einstein. At the Institute, Oppenheimer largely abandoned his research work in physics; the pipe-smoking aesthete preferred to focus his efforts on cultivating a life of the mind, making the tranquil Institute an interdisciplinary haven for humanists—not just scientists—by inviting philosophers, historians, and poets.

Disgraced by his own government, Oppenheimer would dedicate much of the remainder of his sixty-two years to trying to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. In Princeton, in Washington, at universities and conferences around the world, he spoke against an arms race that his epochal work in Berkeley had set in motion. Today, thousands of those weapons sit in their silos around the globe, ready to be launched at a moment’s notice.