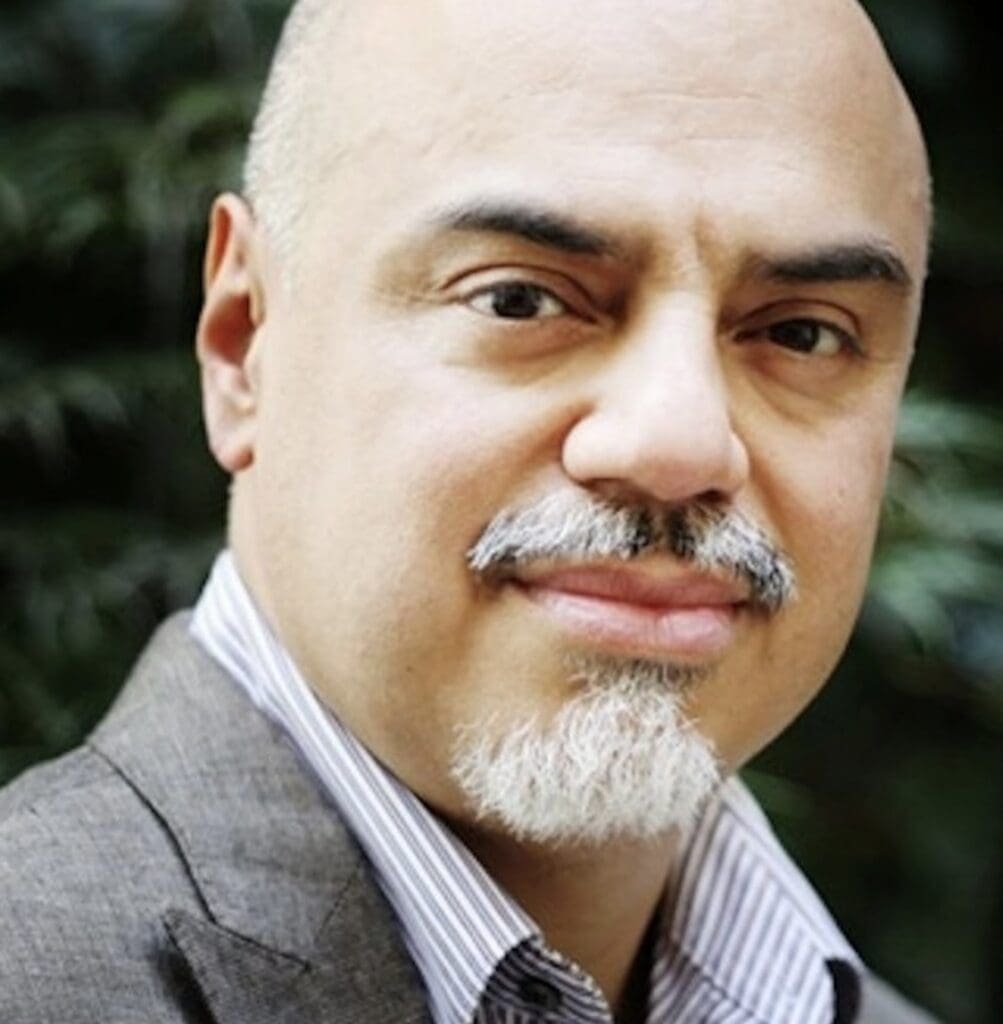

Héctor Tobar has explored Latin American history and the Latino experience in numerous award-winning best-selling works, ranging from novels (The Last Great Road Bum, The Barbarian Nurseries, and The Tattooed Soldier) to nonfiction books (Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free and Translation Nation: Defining a New American Identity in the Spanish-Speaking United States). Tobar has also published fiction and nonfiction in Zyzzyva.

In his latest book, Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino,” Tobar delves with great candor into his own story—as the son of Guatemalan migrants—and that of many newcomers who have struggled to gain acceptance in this country. In the process, he offers a stinging critique of a capitalist system that continues to feed off divisions based on supposed differences between racial groups.

This interview is a transcript from a conversation held at City Lights Books in San Francisco earlier this year. It has been edited for length and clarity.

JOHN McMURTRIE: Much of Our Migrant Souls is an examination of the way things are: Why is there a closed border between the U.S. and Mexico? Why are “‘ethnicity’ and ‘race’ sold to us as boxes containing our skin tones and our surnames?,” and why do we have terms like Latino?, which you use in quotation marks. Could we begin with you explaining the origin of that term, “Latino”?

HÉCTOR TOBAR: The term “Latino” has a very strange provenance. I write in my book that it’s like the terms in Star Wars—Wookiee and all these other made-up sort of tribe names—it’s kind of the same thing. Because “Latino” comes from “Latin America,” which itself is an invention, essentially, of the French in the 19th century. France wanted to take over Mexico, and they told the Mexicans, “Look, we’re different than those Anglo Americans because they don’t speak a Romance language—we are closer, we’re Latins like you. And so we’re sending over this guy, Maximillian, to be your king. But he’s really one of you.” And, of course, [the Mexicans] later executed him. So that idea of Latin America, that we have this commonality as people of Spanish descent with the French, is an invention of an imperialist competition.

Later, Latino people in the United States, we’re given this term “Hispanic” because we have this Spanish origin. Well, people don’t like that term because it sounds English, so people use Latino instead because it comes from Latin America. One of my many problems with all these terms is that they’re silly, but “Latino” erases the fact that we’re also indigenous and Black. So “Latin” is, by definition, this European term. And this is what has happened to Latino identity with all of us—we have these family stories in which we’ve erased our indigenous history, we’ve erased our indigeneity.

At the same time, it’s an expression of a kind of an alliance. So, for example, I have a friend who is colombiana, I am Guatemalan, I know a Puerto Rican guy—we all have a dinner together for an event we’re holding. It’s a Latino event instead of being a Colombian Guatemalan Puerto Rican event. Because we do have a lot in common, like the fact that we have ancestors who crossed the border or who crossed the ocean. So, these terms, they have all kinds of hidden meanings and stories behind them.

JM: Your parents are from Guatemala, and you grew up in Los Angeles, in East Hollywood. There’s one piece in the book that’s quite powerful, and not just because one figure shows up—enough to give you chills. Tell us about your neighbor when you were a kid.

HT: The whole chapter, which began with an article for The New Yorker, was about how I lost my innocence about race. I grew up in a very sheltered, very protected family. My family protected me from the idea that I was different. I thought about the place where I grew up—East Hollywood—very racially integrated, like a lot of neighborhoods in San Francisco. And I thought about its history, and discovered that I lived 100 feet from James Earl Ray, the man who assassinated Martin Luther King, Jr. And I thought about how this neighborhood had harbored this white supremacist who committed this horrific crime. And so I write about his life—he was somebody escaping from poverty, like my father was, actually. He had a lot in common with my father, who at the same time was a leftist, very much a fan of Che Guevara. So they were at opposite sides politically, but they were both people running away.

There’s another character in that chapter, Booker Wade, my godfather, an African American man who had participated in sit-ins at the Memphis Public Library against segregation. He was busted at the library, harassed by the police, so his mother put him on a bus to L.A. As a teenager, he comes to L.A., he becomes friends with my mother, and he becomes my godfather because he drove my mother to the hospital when she went into labor with me. So my life at a really young age crossed paths with this virulent white supremacist and this African American activist. It might seem strange to the reader that my life crosses paths with these two very different people, but that’s the United States—we’re always placed inside the middle of this drama. And really, all it takes is a little bit of investigating to find out how our life crosses paths with American history.

JM: You write that this country has experienced waves of discrimination against any number of its people, and the hope is that white people over time will be more welcoming of people who aren’t like them. But the distressing reality is that there always seems to be another group to attack, whether it’s Asian Americans or gay people or, as we’ve seen lately, gender non-conforming people. It seems to be an intractable problem. I’m wondering if you see it that way.

HT: I started writing my book because I’m a professor at the University of California, Irvine. Part of that is being a person who imparts knowledge, and part of it is like being a dad. There are all these twenty-year-olds who come through, and they have all this longing. They want to read, they want to have all the books seep into their brains and become strong. But they live in this world with all this hatred. They tell me these stories about the ways in which their parents and their families have been belittled as Latino people, or the ways they’ve been traumatized by crossing the border, by separation from family, or by their status. I wanted to give them a book that said, “Look, it’s right for you to be hurt, it’s okay for you to be hurt. These are the reasons why we’re in this situation. And there’s nothing wrong with us.” Because there’s a real sense among Latino people that there’s something broken about us. The book lays out all of this history, to show our story in terms of Chinese migration and the Chinese Exclusion Act and Dred Scott and slavery and the construction of Black as a racial identity. Our story fits inside that story. To me, it’s a lot less overwhelming when I see it as part of this landscape.

But part of it, too, is that the construction of race is this constant in American history. There’s this stereotype that because I’m indigenous, Latino, I’m not smart, I don’t want to work hard. That’s what race is—this notion that there’s a group of people who share common biological traits, and that shapes who they are. Now, science has now shown that’s bullshit, so what’s interesting is the way we always are constructing new ideas of race. When I end the book, I talk about how you can imagine a future where even if I could give everybody a pill that erased all of the racist ideas from our minds we would still invent new ideas of race to explain why there are poor people and rich people, why there are people living in apartments and why there are people living on the streets. That’s the journey that I’ve undertaken with this book, intellectually—to arrive at this understanding of race as essentially part of this capitalist system that is constantly inventing new terms to divide us.

JM: There’s one sentence in your book that encapsulates the uglier side of democracy that many of us don’t see or choose to ignore: “Ethnic hatreds and race engineering are the dark force that created the modern world.” Can you elaborate on that?

HT: In the United States, our comfort is based on systems of inequality. It sounds rhetorical, it sounds like I’m standing on a soapbox—and it just happens to be true. The coffee we drink, the labor that’s required to bring the water to our tables, the coal that keeps the lights running—all those things are constructed from human labor. There are the people who do the work, and the people who benefit from it, and that’s just a constant, I think, in human history and in our present.

In the media, you see all these images of the masses at the U.S.-Mexico border. You see these groups of people, and they do this wide shot, with drones, and they show hundreds of people in front of the border and this image of this chaos, and they tell these stories—“they’re going to run across the river, or there’s not enough shelters for them.” That’s the dominant image of Latino people in the media. But to me, the dominant image of Latino people is when I drive through a suburban neighborhood and all the lawns are perfectly cut and all the shrubs are perfectly cut, and there’s a lady walking a little boy in a stroller. And when I see people coming home with their groceries—90 percent of the food in this country is picked by Latino workers, and half of them are undocumented. That’s the image to me of Latino people. What’s happening at the border is a tragedy, and we should know about it, but it’s frustrating to live in this media orbit where we’re just being fed these one-dimensional, stark ideas of who a people are.

JM: Though, you do write about the border—specifically about one anthropologist, Jason De León.

HT: Yes, a MacArthur winner. Jason De León is this anthropologist who was trying to answer the question, how many people are really dying crossing the desert? So, he went to go see what happens to a body when someone dies in the desert. He took these corpses of pigs, put them out in the desert, and examined what happened to them—hidden cameras and everything. There’s this whole natural cycle of what happens to a corpse in the desert. First are the feral dogs and the wolves and the vultures, and within a few weeks, most of the bodies are erased. Essentially, he discovered that nature was doing the dirty work of American immigration policy, because nature is erasing the bodies. And I wrote that it’s a perfect sort of mass murder because it’s taking place where there are no cameras and the bodies are erased.

JM: What was your path to becoming a writer?

HT: I’ve always loved to write. And my father, he always loved going to bookstores, loved reading. I didn’t know this until I had written my fourth book, but his mother was illiterate, so my father had this shame about that. This is common in Latino families. Female illiteracy is really high because it’s not seen as important in poor families to send girls to school. My first expensive present that I got was a brand-new first edition American Heritage Dictionary of the English language. I realized that my father, who had a mother who could not read any word in any language, had given me, his son, all the words in English.

So I always had this respect for the book, but I didn’t know that you could be a writer [laughs]. I didn’t know that was a job. And it was only when I moved after college to San Francisco, and I started coming to events here [at City Lights] and at Modern Times in the Mission District that I met published writers. The first I ever met was Ariel Dorfman, the Chilean critic and playwright. And then I met Sandra Cisneros at another event, and I was like, wow, maybe I could do this.

Later, I became an editor at a newspaper by accident. I was in the Mission District and I wandered into a panadería and they had a stack of these free newspapers, El Tecolote. I picked one up and it said, “We need volunteer writers and editors.” I went to volunteer, then within six or seven months of me being there, they said, “We just got a grant from the San Francisco Foundation. We can pay you $9 an hour to be the editor.” I said, sure. And that was my first-ever paid writing gig.

I always equate this bookstore—and it makes me want to cry, thinking about it—with my introduction to the culture of the word and San Francisco with the beginnings of my literary awakening. And now my books are here, not too far from Tolstoy—Tobar, you know [laughs].

JM: What advice might you have for Latino people who want to become writers?

HT: I think that we don’t realize the profundity and the epic nature of our own stories. A lot of my students, they haven’t really read a lot of great literature about the Latino experience. Those books are out there, and when I give them those books, they’re excited about them. But they may think of themselves as people not of consequence. I ask them to write stories for me. I tell them, write me a story about the Latino experience. That’s it, that’s the parameter I give them. And I tell them I want it to be true. That’s sort of what spurred the book. I got all these stories of border crossings, or fathers who were alcoholics and then born-again, or fathers who were gardeners and built a whole empire of tree trimming—oh my God, these incredible stories. To me, the most important thing is to realize how profoundly awesome those stories are.