I’d started tending the ex’s plot. The lettuce and the garlic and the turnips. It wasn’t my idea, the apartment complex had a community garden, and of course I’d seen you out there but we didn’t have shit to say to each other.

We met on the stairs after my guy left, and it was another few weeks before we spoke. I’d seen you around, though. Sometimes I’d catch you staring. Our eyes met, and you’d look away. You were an old man, living alone, always in the same greasy cardigan and the same burnt brown shoes, which was everything I never wanted to be, or so I thought, at least back then, and one day I told the ex all of that and he just gave me this look.

But then—the split. Which left me solo.

Afterward, you only ever saw me in sweatpants, dumping six-packs of Karbach in the dumpster at the end of the week.

By then, everyone else’s vegetables were jumping into bloom. I watched Isabella and Jiao and the other neighbors prune their soil indiscriminately. But all of my shit started dying, and I was never entirely sure what was wrong, because I’d never seen the ex break a sweat over the garden, which he’d maintained silently. Meticulously. Whatever he’d done seemed to work without a hitch.

Houston keeps a tropical climate. A boon for the earthier strains. In some ways, my fucking everything up was as remarkable as anything else.

One afternoon, I’d poured the last of like five water bottles over the spinach when you stopped me.

Kid, you said, that’s not the way. You’re gonna drown them.

Hasn’t happened yet, I said.

That’s a sign. It’s the roots talking. You’ve gotta listen to them.

I’m good, thanks.

And then you nodded, like, All right, you little bitch.

You hobbled back to your own patch of green, with the mustard and the collards. They pulsed, blooming over everything else. Casting these big-ass shadows across the lot.

A few weeks later, everything was fucking dead.

Jiao and his kid watched me size up the remains. The soil cracked under our Vans.

Damn, he said. RIP.

Bullshit. They’ll come back.

No doubt, said Jiao. We just might not be here to see it.

Then he and his kid crossed themselves, sending two fingers skyward. I didn’t have time to stage an agricultural revival. I was still working downtown. Still had the temp thing at the ex’s office on Elgin and San Jacinto. We’d pass each other on the staircase and I’d think: I used to fuck you, you’d bend me entirely over a chair—once, twice, three times a day, even, I’d let you finish wherever you wanted, wherever you asked, at any time of day.

But what I actually said was, Hi.

And then the ex said, Hey.

And that would be that. We went right back to our new lives.

Then one day I came home to a crowd standing over my garden graveyard. Legit concern creased their brows. They were literally thinking aloud. What could’ve gone wrong? Everything’d been fine a few months ago. The owner had clearly fallen off, they needed their space revoked, it was an embarrassment to the community.

I watched everyone through my shitty little window. And then I saw you, stooped over the railing.

I waited to see if you’d join in the fun, but you didn’t even look up. You just tended your own shit and turned your back and walked away.

That weekend, I was waiting for a hookup to roll through when you knocked on my door. I answered in some boxers.

I said, You know where I live.

You just rolled your eyes. We were the only two black guys in the complex. Everyone knew where we lived.

These books sat under your arm. Their covers featured avocados and tomatoes strung together with looping vines. On one, a white woman perched over this granite counter, hidden under what looked like a discount sombrero.

Read the Kennedy first, you said. It’ll bring your garlic back.

No shit, I said.

Correct, you said. The onions, too. Once the humidity’s dropped, they’ll recover.

I took the books from you, not really looking at their covers. We slumped in the doorway, kicking sideways at the carpet.

So, I said, and that’s when you shouldered past me, and I’m not the smallest guy in Texas but you moved pretty quickly for an old fucking man.

You scoped out the walls of my apartment. Not that there was much to see. I had this PS4. A busted coffee table. A deck of torn playing cards. Miyazaki DVDs scratched beyond recognition. And for reasons I still can’t explain, I didn’t do shit to stop you: I just watched you wander from room to room, wiping your fingers at all of the dust.

You’d grunt, from time to time, tapping and rubbing at the counter. No books, you said.

Are you a goddamn librarian?

I’m a human being, you said. Open your brain.

I work, I said, but you weren’t listening, already drifting again, whistling now.

After a lap around the living room, you picked at a quilt on the sofa. My grandmother, a devout homophobe, had knit the thing decades back. I’d made a habit of fucking on it regularly, wrapping it around my shoulders afterwards, and you sat yourself across from the thing, crossing your legs at the heel.

Not much here, you said.

You’re in a stranger’s home, I said.

Well, you said, and then you let your gaze linger, sloping casually to my legs.

It was pretty late now. My hookup still hadn’t knocked. You extended a finger, grazing my knee, and when I looked up, you’d raised an eyebrow. If I hadn’t done anything, hadn’t fucking responded to your touch, it’s worth wondering what would’ve happened. How all this would’ve turned out.

But I set a hand on your shoulder—and that was it.

You grabbed the backs of my knees, setting my ass on your khakis. When I didn’t give, you tugged harder, until I sort of collapsed on your shoulders. With your toes on the carpet, you started pushing me out of my sweats, before you, slowly, inched my back on the sofa.

Whoa, I said. Whoa whoa.

Do you need me to stop, you said.

You don’t need to take it slower? Can you even do this?

Fuck you, kid.

I’m just saying.

I was fucking before you were born.

You look like you’re right around the corner from the grave.

And you grimaced at that. But I relaxed a bit. It lightened the mood. Which meant that we were grinding, again, with my chest on yours, and your mouth on my ear and my lips on your neck, and I let you set the rhythm, until I decided not to do that anymore, and eventually, I grabbed our dicks with one hand, squeezing your shoulder with the other, and you groaned when I came, and I laughed when you came, and once you’d finished, gasping, I rolled off of your lap, waddling to the bathroom.

What we’d done, and how quickly we’d done it, didn’t hit me until I’d finished washing up.

So I listened through the bathroom door. Thought about just letting you leave, because maybe you’d get the hint. You probably had kids. Grandchildren. A wife. The whole thing. It wouldn’t be the first time. We’d pretend this shit never happened.

But then, from the living room, you said, It’ll come back.

What, I yelled.

Your garlic. Once the cold spell’s over, it’ll come back. That’s really what you want to talk about right now? It’s what I knocked on your door for, kid.

Stop calling me that.

It’s what you are.

I’m not a child.

Wait until you’re my age. You’ll wish someone called you kid. Then the two of us sat silent on both sides of the door.

Well, I said. Thanks for nothing.

Look, you said. Kid. Guy. Whatever. Your plot looks like shit. It’s fucking up the garden. No one else will tell you this. Young guy like you, they probably think you’ll jump on them.

Guess that makes you a good fucking Samaritan, I said.

Let the cold front pass, you said, again, and that’s when I finally opened the bathroom door.

But you’d already made it down the hallway, shutting your own door behind you. Leaving mine ajar. I thought you might turn around on your way down, but that was just wishful thinking. You were already gone.

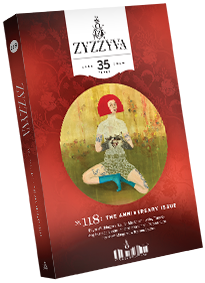

Bryan Washington is an American writer. He published his debut short story collection, Lot, in 2019 and a novel, Memorial, in 2020. Read “Community Plot” in its entirety by ordering a copy of Issue 118 today.