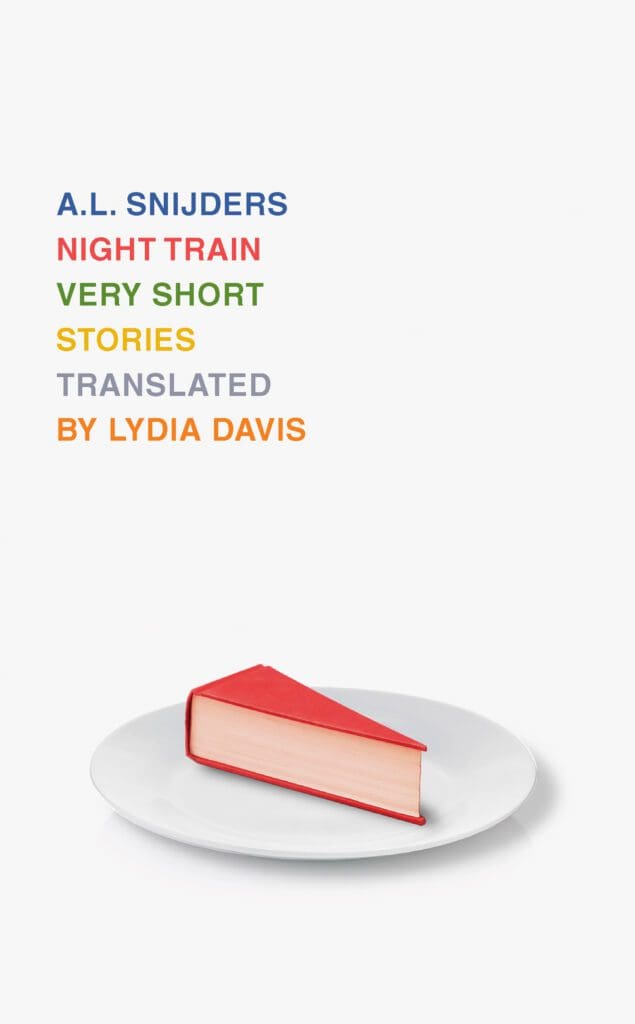

When she began translating contemporary Dutch micro-fiction writer A.L. Snijders’s work, Lydia Davis had only a passing familiarity with the language. Night Train (128 pages; New Directions) presents 91 of Snijders’s more than 3,000 stories, or what he called his zkv’s (zeer korte verhalen: “very short stories”). The collection is a long-tended-to anthology of these writings—“autobiographical mini-fables,” as Davis calls them—whose translations she parsed and reasoned-through using what she knew of German and French, and with the consult of Snijders’s Dutch publisher, Paul Abels. Many of the pieces parallel the tone and form of some of Davis’s own vignettes: stories bloom within a narrow constraint, with a dialed-in, quotidian poetic (most are 300 words or fewer).

Snijders made a point to publish each story he wrote without exception or much in the way of editing; many appeared in the local newspaper of his hometown, and many he read over the radio and on television. He passed away in 2021, just as Night Train was on its way to the printer—reportedly dying at his desk, in the middle of writing a zkv.

“In all his depictions, there is wit, wonder, a gentle humanity,” Davis writes in her introduction. “Characters appear and disappear, there only for a moment but fully alive.” Most of Snijders’s stories center on the everyday: his home life and family, his neighbors, his experiences with the animal world and with strangers. The zkv’s are firmly situated in Holland, in places Snijders “frequented or remembered from his past,” Davis notes. At the back of the book, she footnotes the various regional and cultural references in the writing, indexing historical and literary mentions such as early and contemporary Dutch writers, as well as TV show hosts, politicians, and cafes. Kees Otten, we learn, is a world-famous recorder player; Eieren kiezen voor je geld (“He had taken eggs for his money”) is a Dutch expression for “playing it safe.”

From “Luck”:

I yearn for the stories the recorder can tell over a hundred years—who, in that time, blew their poetic breath through that wooden body? For musical instruments can live longer than people, with a little luck, and I suspect they are also endowed with better memories.

Though much of the writing is fictionalized, we receive select glimpses of Snijders’s life throughout: the story of his mother’s fall from a window as a baby (“Years”), derisions of his Catholic upbringing (“Town Line”), the night when his granddaughter woke him after a bad dream (“Story”). In “Shoe,” Snijders mentions doing poorly in school as a young person and receiving criticism for the brevity of his writing (“too lapidary”), a penchant he later put to good use—making, in his words, a “virtue of necessity.”

. . . we drink wine and don’t force anything, we let fate, so-called, do the work. Mankind should not interfere with everything. It takes some time for the Montelbaanstoren, the snakes, and the harpsichord to open the way. And then not even with an Ah or an Oh, there is no sudden breakthrough, we are embarrassed by the pussyfooting march of time.

Aside from their concision, Snijders’s zkv’s vary greatly in their scope and pacing. Some, Davis writes, are “an almost static snapshot, some a neatly bounded narrative, some a meander.” His zkv “Box” reads:

My youngest son has a girlfriend (could I also write his girlfriend has my youngest son?). They’re going to have a child in November. My youngest son wants to put it in the same box he himself lay in, thirty-seven years ago. The box was nailed together by me and coated with primer. It was never painted. I look for the box in all the attics and in the hayloft and on the side platforms of the hayloft. I have four fully loaded barns, two made of wood, two of stone. I look everywhere, I can’t find the box, the days are passing. This morning at eleven thirty, in the full sun, I go and look in the last uninspected place, in the locked, nearly impenetrable part of the second wooden barn, where I haven’t been for years. I climb over boxes and shelving, and open the door. A frightened owl flies straight at me, dead quiet, as quiet as a shadow can fly, I look into his eyes—he’s a large owl, it’s not strange that I’m frightened too, we frighten each other. I myself thought that owls never moved in daytime. What the owl thinks about me, I don’t know.

The principal through-line in Night Train is Snijders’s depiction of “our shared habitual uncertainty”; wonders and doubts are held intact, unanswered, and speak to Snijders’s distinct humility as a storyteller.