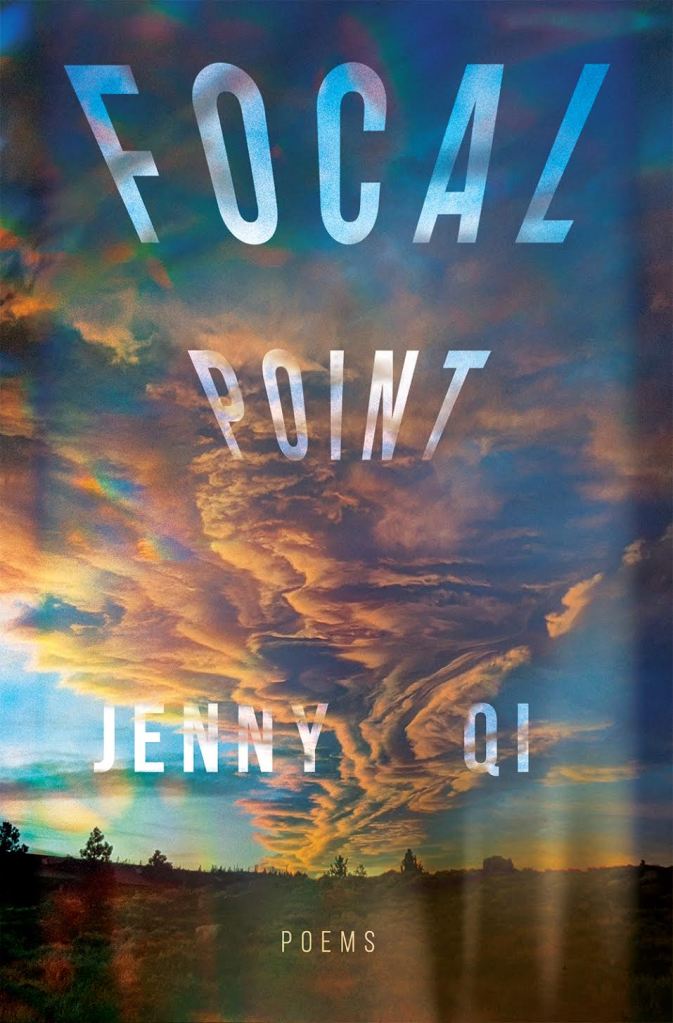

Jenny Qi’s first poetry collection, Focal Point (98 pages; Steel Toe Books), sees release this week. Written over the course of Qi’s graduate study in oncology, and upon the loss of her mother to cancer, Focal Point quilts together meditations on memory, bereavement, racism, divinity, and motherhood. Victoria Chang describes the collection as a “book of crossing.” Its sixty poems forward a fresh, intertextual probe into experiences of transition and bring delicate attention to life in the wake of loss. Qi was the winner of the 2020 Steel Toe Books Poetry Award, and her essays and poems appear in the New York Times, The Atlantic, and the San Francisco Chronicle. Two poems from Focal Point, “Little Fires” and “The Next Great American Love Story,” were published in ZYZZYVA Issue 108. Qi spoke to us about the collection via email.

ZYZZYVA: You note in the opening of the collection that you’ve dedicated the poems to your late mother, and much of the writing reads as a direct address to her and to the memories you two shared. Was she the primary reader you had in mind as you wrote through these pieces? Did you have any other imagined readers you sought to address?

JENNY QI: I think from a young age I’d learned to write in the second person when I was grappling with strong emotions, such as to a diary or to nonexistent blog readers, and so that felt most natural to me when writing many of these poems. I remember reading an interview with YA novelist Jenny Han, who wrote To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, about how she used to write letters to people and never send them, and I guess I kind of did that, too, though usually not to a specific person so much as to the nebulous world beyond me. I used to write letters to myself when I first moved to San Francisco, and I think that was another reader I had in mind for many of the poems. While I didn’t consciously think of this while writing, Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet really spoke to me as a younger person in need of guidance and understanding, and I think that yearning informed some of my early writing.

Z: Given that this is your debut book of poetry, I’m curious to know more about your experience bringing the poems together into one collection. What did that process look like? Did you find there was a natural or obvious arc/momentum in the collection as you put it together?

JQ: The collection went through a few iterations before it reached its current form, and I took long breaks between iterations. When I first started, I really didn’t know what I was doing and had to spend time learning how to read a poetry book as a writer and consciously thinking about how to put together a collection such that it might become more than the sum of its parts. In my first attempt, I really struggled to not compartmentalize by subject or just put everything in chronological order, and I put all the heavy grief poems together without giving readers any breathing room in between. While that felt true to the relentlessness of early grief, it didn’t allow for a full picture of living with grief and its recurrence, and it was probably a slog to read. Each time I reordered the poems, I had to sort of re-create the process of grief and more importantly reimagine what this book could be beyond my grief. What stayed fairly consistent through subsequent iterations was the first section of the book, but as I grew older and more able to look outward beyond my personal grief, the later sections changed to reflect that.

Z: How did the various poems called “Biology Lessons” come into the collection, and how do you see them interacting with the rest of the writing?

JQ: I wrote these poems very early in grad school, and they were just a series of quick observations that I found compelling when I was reading a lot of scientific papers for class and first learning to culture cells (i.e., grow them in a dish). I probably wrote them as part of my annual National Poetry Month challenge, in which I wrote a short syllabic poem each day for the month of April. I didn’t know what to do with these poems afterward and never really thought about them again until after I graduated. I also wrote a lot of shorter “how-to” poems that were more about learning to be a writer, only a couple of which made it into the book, and I view these as being of the same spirit. All of these poems were a sort of poetic lab notebook in which I recorded my observations during a time when I was learning and navigating so many things—how to be a scientist, how to be a writer, grief, growth, etc.

Z: Where did the idea for the collection’s title, Focal Point, come from?

JQ: “Focal Point” was initially the title of an earlier version of the first poem rather than the title of the collection. The poem’s current title, “Point at Which Parallel Waves Converge & From Which Diverge,” is the definition of a “focal point” in optics. “Point . . .” was one of the later poems written, and in the writing of that poem, I was grappling with the illogical and often self-centered ways we process grief and emotional pain and thinking about how the different definitions of the term “focal point” apply to it. I knew that poem was critical to the collection, and I realized it was because the collection as a whole engages with the same ideas. Loss is the central focus of this book and the point at which every moment becomes a time before or after loss, even though there’s so much more happening around it. And when I realized this, I moved the opening poem from the end to the very beginning, viewing it almost as an abstract in a scientific manuscript, which is the first section that synthesizes what the manuscript will be about.

Z: Poems like “Radiation” and “Telomeres & a 2AM (Love) Poem” give us a glimpse of your doctoral background and ongoing work in cancer biology. How would you describe the kinship you’ve found in your own writing between scientific and poetic expression? What have you found they offer each other?

JQ: I should clarify that I no longer do bench work (i.e., hands-on research in a lab) and haven’t done so since graduating, though I do still work in a science-adjacent role. I’m not sure that my scientific work ever benefitted from my writing, to be honest, because I compartmentalized a lot, and in that part of my life, I felt a lot of pressure to maximize output and be productive rather than creative. I wish I could have found a way to find more joy in it. Poetry, on the other hand, was just a semi-secret thing I loved and did not rely on for my livelihood, so I didn’t have those pressures, and it was where I funneled all these nonlinear, sometimes illogical thoughts that popped up as I learned cool new things about (cell) biology. My writing has probably benefited from my science more than the reverse because science gave me a different way of doing things and looking at the world, a niche body of knowledge, and a whole other set of vocabulary to borrow from. I feel like that’s such an obvious thing to say, that one’s writing benefits from the experiences one has outside of it, but it’s true.

Z: I noticed there were a few different references in your writing to Greek mythology, including references to Circe and the river Styx. What drew you toward Greek stories and figures in these poems?

JQ: When I first started writing poems, I wrote a lot of persona poems, finding points of connection with and embodying people who were seemingly very different from myself. I always loved mythology, sort of indiscriminately, but perhaps what drew me to Greek stories early on was that they were so human and terrible and relatable. I didn’t know what it was like to be a sorceress, but I knew isolation, rage, longing. And it’s very likely that I felt this way about Greek mythology specifically because that was what I was most exposed to in school and in Western literature. I’ve written some poems referencing Chinese myths as well, but those never felt finished.

Z: With the many relocations you made as a young person, this collection seems markedly grounded in place, in San Francisco. Do you feel a strong connection to the city?

JQ: As you mentioned, I’ve moved around a lot, and I often did so knowing it was temporary and out of my control, so I always felt kind of emotionally transient and rootless. San Francisco was different, because my transience wasn’t a certainty, and I decided this was where I was going to invent myself. I read Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides either shortly before or after moving, and the image of the fog as a kind of sanctuary as well as a metonymy for the city has always stayed with me (even if I don’t always feel positive about it). I was very young when I moved to San Francisco for grad school, and it was just a few months after my mother died, so I grew up a lot here. My experience was heavily colored by my grief, and for that and other reasons, it hasn’t always been an easy place to live. But at the end of the day, San Francisco is the place in which I made a conscious choice to grow into myself and move forward when those things felt impossible. At this point, I’ve lived here longer than I’ve lived anywhere—it’s the only home I’ve ever actively chosen.