ZYZZYVA: In Thousands of Broadways: Dreams and Nightmares of the American Small Town (2009), you write fondly of your dad, a star basketball player, trophy in hand. Is there a game/sport you enjoy playing?

Robert Pinsky: In high school I was not bad at the team sports, and as a Stegner Fellow at Stanford I was a standout in Sunday morning softball games, (Not saying much—as tiny a distinction as the Hemingway character’s boxing championship at Princeton.) For years I got great pleasure from tennis, but at some point, writing became the one theater for all my efforts of a certain kind.

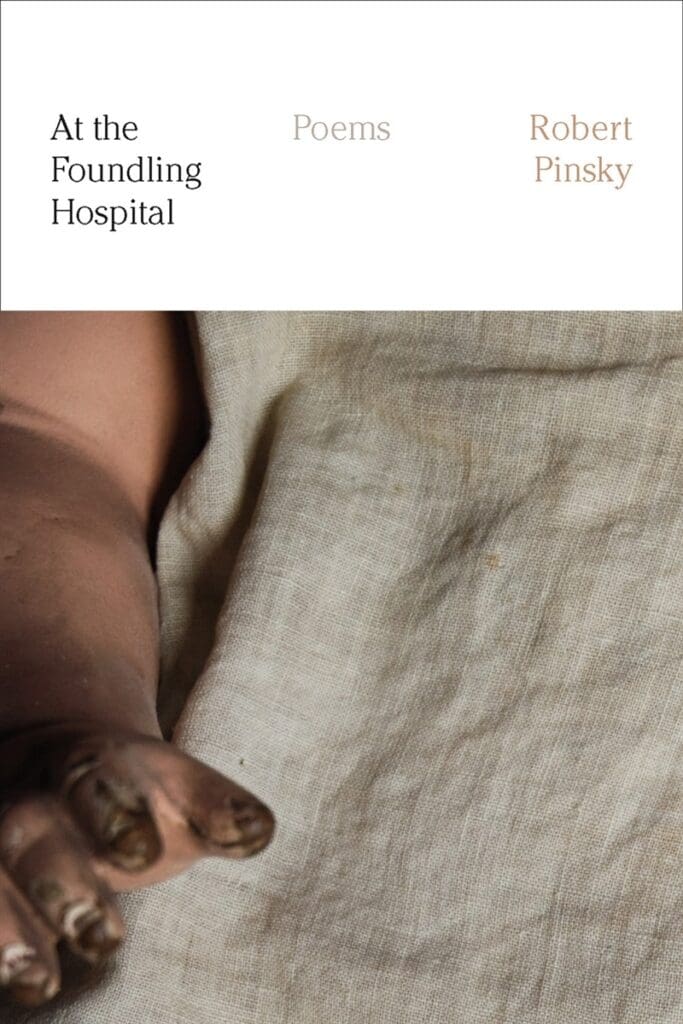

Z: Regarding “The Foundling Tokens,” can we ever reclaim a past from pieces left behind?

RP: I’m tempted to say, that is all we can do. There is no time machine, no perfect recall, no ultimate authority. We look at the pieces and try to think and feel our way toward understanding them…if not entirely reclaimed, partially so—as great works of art and science have done, I think.

Z:Is there a painting, when first viewed, that made you feel light, connected to the world?

RP: Often—maybe revealing of my naivete, often with faces.

In the Prado, amid Goya’s gorgeous portraits of kings and duchesses and big shots wearing amazing finery, even their horses with expert hairdresser-work, there was a portrait of a man plainly-dressed man sitting at a desk, his head resting on his hand, a paper document in his hand, with a remarkably intelligent-looking, careworn face: Jovellanos, the great humanist and I think protector of Goya. I remember being surprised to find that the contrast with the royal ninnies brought tears to my eyes.

And in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts a few years ago, Goya’s painting of himself being treated by his doctor: the painter sort gasping, the doctor’s hands, eyes, angle of head, all expressing careful, earnest, humanistic attention. And the same contrast with the over-dressed, over-primped royalty and big shots around them, the “celebrities” of that time and place.

Z: Over the course of this last year, 2020 and into 2021, how have you been?

RP: During the rise (or re-birth) of fascism, the pandemic, the bad government, my family and I have been blessed with good health, some laughter, decent work to do, company during the stress and anxiety.

Z: In the opening stanza of “Long Branch, New Jersey”

Everything is regional,

And this is where I was born, dear,

And first moved to tears,

And last irritated to the same point.

When was the last time you were moved to tears?

RP: A bit embarrassing that I just used the same expression, telling about the Goya paintings. But there it is: I do cry rather easily, for instance reading the newspaper. One of my grown children told a story, at dinner, about something funny I said many years ago…I was so pleased that I surreptitiously bawled a little.

Z: When was the last time you were wrong?

RP: Last night, meaning to stream the brilliant comedy Galaxy Quest, I instead cued up the lousy turkey (unworthy of its good title) Earth Girls Are Easy.

Z: Is the concluding snapshot of a smiling family, framed with two looming shadows, a depiction of Dreams and Nightmares of the American Small Town?

RP: It’s a natural conclusion that it’s a family, but the two little boys in cowboy suits, holding hands, are my childhood friend Carl Mehler and me. The woman behind Carl is my mother, and for years I assumed the woman behind me was Carl’s mother—but Carl (we graduated Long Branch High School together) assures me that it is definitely not his mother. So, she and the baby are unknowns—unassigned pieces in that project of reclaiming the past.

The shadows, I assume, are of my father and the unknown woman’s husband, with the sun behind them, one of them taking the photograph.

Z: When organizing your poetry, has your method changed since your first collection?

RP: “Organizing” is not my word for what I do, and I’m not sure “method” is either. I don’t want to pose as an airy, impulsive spirit– using your rational brain is fine with me. But both “organize” and “method” suggest the kind of approach that has scared and upset me since kindergarten.

If you mean the order of the poems in a book, I have always gone by intuition, tempered by advice from friends and editors. If you mean how each poem is put together, in a different way I have always relied on the same two elements.

As to changes over the years: I think my energy is more and more devoted to ear and impulse as ways to inspire thought and purpose.

Z: At this point in your career, does your poetry, literary work, every get rejected?

RP: Not much. (Not often enough?—always a danger, I guess.) It happened not long ago— seemed painful for the editor, but not for me. I think he was very anxious about an “identity” issue.

Z: In “Visions of Daniel,” I was struck by the stanza

The Jews disliked him,

He smelled of pagan incense and char.

Pious gossips in the souk

Said he was unclean,

He had smeared his body with thick

Yellowish sperm of lion

Before he went into the den,

The odor and color

Were indelible, he would reek

Of beast forever.

Is lore, of being human, a form of inspiration?

RP: What an interesting question, with that quotation. Yes, the protective, ambiguous stink of information, with its bodily, practical, communal human sources, is a form of inspiration.

Z: With your writing, do you hope to inspire, guide people to their own stories?

RP: Maybe not. I mean, it is a great compliment if someone tells me something I wrote inspired or guided them in their writing. But I’m thinking about how this little spring regulates that lever, and how the number 6 brass oval head wood screws could have matching brass washers, or how this particular pie would go well with a graham cracker crust—technical issues.

Or maybe while writing I am thinking about Arthur Rimbaud or Emily Dickinson or John Dowland and wondering how they’d size up what I’m doing.

But maybe yes, when I stand back from it, you are right: I do hope to inspire, guide people to their own stories, the way Willa Cather in The Song of the Lark guided me to mine.

Laine Derr holds an MFA from Northern Arizona University and has published interviews with Carl Phillips, Ross Gay, and Ted Kooser. Recent work appears or is forthcoming from Antithesis, Portland Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere.