Superstar author Haruki Murakami has published twenty-three books (in English) since beginning his career as a novelist in 1978. In his strictly upward trajectory, full of merits and awards, he has not had much space for rumination. However, in his new story collection, First Person Singular (256 pages; Knopf), he channels 72 years of writing prowess into a series of mystery-dipped stories about youth, memory, and identity.

Each begins with a distinct memory, an arresting one. “A dimly lit hallway in a high school, a beautiful girl, the hem of her skirt swirling, [holding] With the Beatles.” The speaker tunnels in on the details, repeating them to himself in myriad ways, utterly captivated, almost at the expense of the story being told. Murakami’s narrators are hardly fit to narrate, so distracted are they by these images and their other peculiar dispositions. They miss chances to forward the plot, passing up opportunities to see an old friend’s mountaintop piano recital or to purchase an actualized version of the album they fabricated two decades prior. They get distracted and miss the point: while receiving a private concert from a twenty-years deceased jazz musician, the speaker of “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova” thinks, “And I was strangely impressed that in the midst of a dream I could catch, so very clearly, the enticing smell of coffee,” and the speaker of “Carnaval,” upon learning his long-time friend is a wanted felon, considers that friend’s physical unattractiveness.

This latter distraction is one of the collection’s most interesting and common. First Person Singular is full of layered women who write evocative Tankas and create outlandish scenes. But rather than ponder those actions, these speakers’ minds return to some daft, sexualized facet of the original image, like teeth marks in the towel used to muffle the woman’s lovemaking cries. Even when a former girlfriend, who the main character was drawn to by the “urgent impulse” familiar to teenagers, commits suicide, the speaker can only think “I couldn’t see her as the type…Honestly I thought she was a bit shallow.”

There and elsewhere Murakami generously seeds mysteries that evade the narrator and challenge the reader. For instance, an old man encourages the speaker to consider a “circle that has many centers but no circumference.” And in moments like when a character describes his failing memory as “go[ing] to the dark side of the moon and com[ing] back empty-handed,” mystery penetrates even the story’s language. It is within the unknowing speakers, too, who often know less about themselves than the story does.

But Murakami leaves it at mystery; he never lingers on the morbid. When things threaten to become too serious, his focus returns to the surface. In “The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection,” a story named after a real collection of poems Murakami printed as a fledgling writer, the speaker dulls the disconcerting edge of his father’s death and mother’s illness with a poem titled “Outfielders’ Butts.”

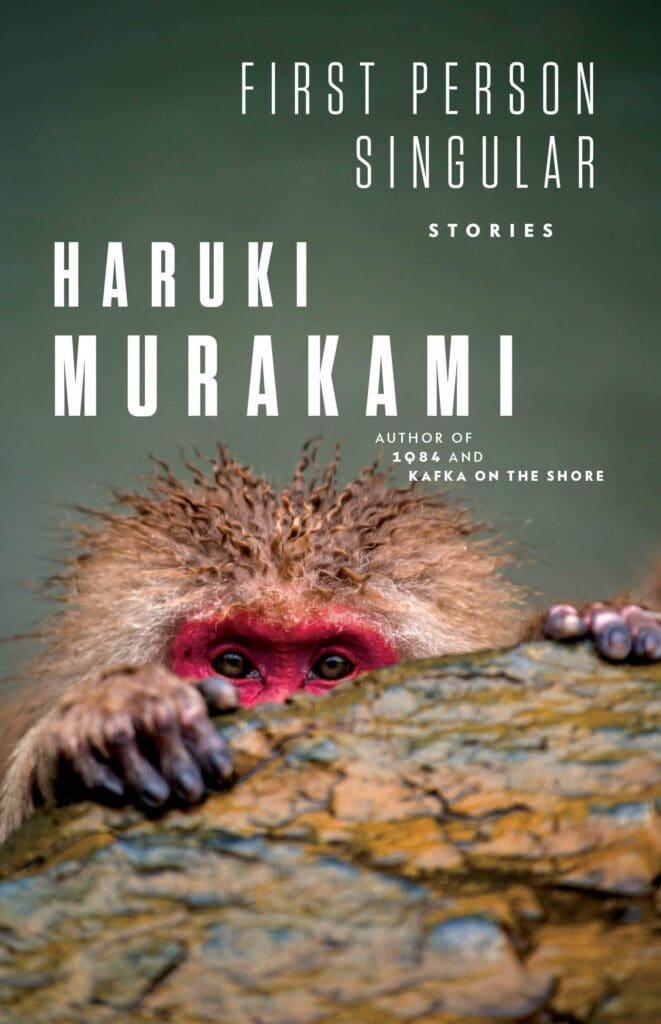

Here, as always, Murakami is original. His prose often relishes its own oddness, expounding its philosophy in opinionated blocks such as, “Of course there was a relatively reasonable answer, but I didn’t really think that arriving at a relatively reasonable answer was one of the goals of studying literature.” He surely believes this, since each story is reasonable only in the most relative sense. If they are not talking-monkey-on-a-kleptomaniacal-quest-for-love bizarre, the stories mash up incongruent narratives or perform daring experiments with chronology and form. They challenge the precision of memory and ask readers: are we what we remember? Are we the same person who transcribed the memory? Even if you know not what of, Murakami’s new collection is certain to make you wonder.