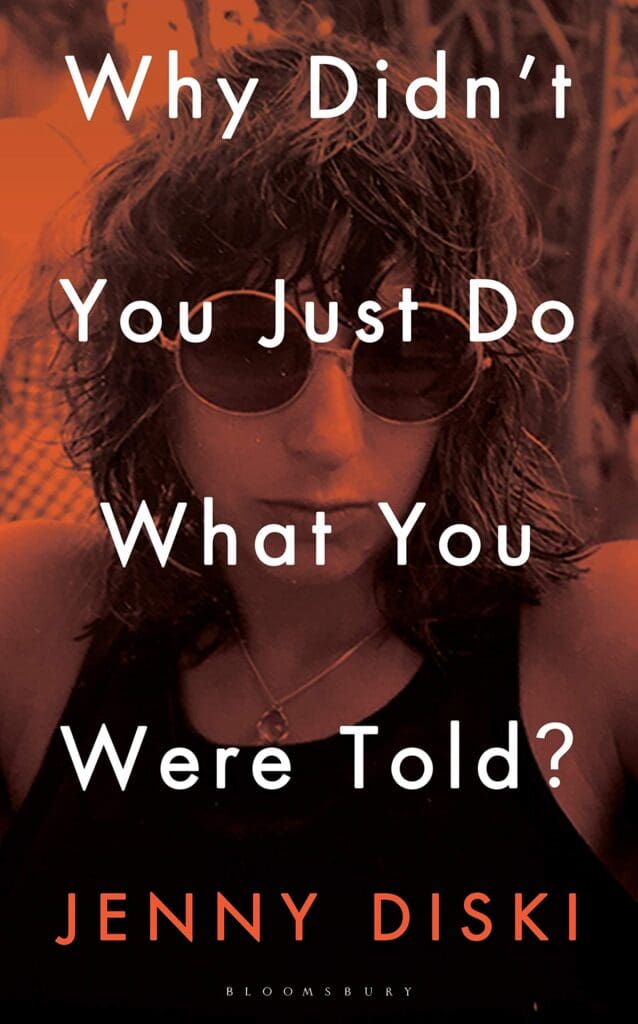

Jenny Diski’s posthumous collection, Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? (448 pages; Bloomsbury), consists of thirty-three essays, selected from the over two hundred the prolific British author wrote for the London Review of Books up until her death in 2016 at 68. Opening with a lighthearted account of a breakup and concluding with a humble meditation on her cancer diagnosis, the book synopsizes the inertia of life. Between those bookend essays are others that tend toward a topic-oriented approach that awards agency to her subject, rather than herself. Writing about Friedrich Nietzsche and his sister Elisabeth, Diski discerns that the two made a “nearly perfect narrative. Most real lives need a good deal of cutting and pasting to get them into story shape. Here, no complicated restructuring is required.” There is a persistent sense, reading Diski’s essays, that little to no “cutting and pasting” lies therein.

A handful of the pieces are explicitly autobiographical: about her troubled childhood, two abusive parents, and some time spent in mental institutions. The majority are about the lives of others: book reviews—of biographies, memoirs, and diaries—in which a curious Diski inquires into the strange lives of strangers. She questions and critiques the profiles of an eclectic bunch (including Véra Nabakov, Stanley Milgram, Howard Hughes, Roald Dahl, Denis Thatcher, Dennis Hopper, and Richard Branson). Her work might be labelled criticism, memoir, and even bibliography-critique, but is better unified by subject than genre. She examines blankness and vacancy, celebrity and suffering, persons and their pasts.

In “I Haven’t Been Nearly Mad Enough,” Diski refutes the practice of psychoanalysis, citing her futile experience with cognitive behavioral therapy and mentioning that “the gap between understanding my situation and feeling better is precisely what has always fed my distrust of the analytical situation.” Investigating powerful people, though, she nearly adopts the psychoanalytic frameworks that she critiques—such that her difficult beginnings and their sustained force are both named and enacted in her writing. Most of the time, though, Diski observes herself with the same objectivity as shown toward other characters. Her authorly narcissism is dissected with just the same precision as Howard Hughes’ indulgent madness. In “A Feeling for Ice,” she selects the third person to reference a younger self as “Jennifer.” Such impartiality reaches far, transcending self-awareness and bordering on dissociation. The most revealing, inward-facing essays of the bunch are not the ones about a trip to Antarctica or weeks spent alone after an ex-boyfriend moved out. They are the ones about Howard Hughes and office supplies. Looking through a window is sometimes the closest thing to a mirror.

While the collection—written between 1992 and 2014—does not feel profound nor groundbreaking in 2021, one gets the sense that Diski did not aspire to such levels. She had little regard for profundity, and instead arranged plain words with an observant eye and a careful hand. It has been said that her essays justify the phrase “reading for pleasure,” and Diski knew well that pleasure can exist for its own sake: in “A Feeling for Ice,”she writes that “the point of desire is desire itself, the essential pleasure in expectation is expectation.” Diski necessarily conceived of reading as an utterly human act, an unremarkable pleasure. She is at peace with her own humanness and that of her reader. Pleasure, of course, always sees its own end. And there is a melancholic and morbid way of seeing that undergirds her self-deprecating way of writing. A tendency toward nihilism cuts through her light humor. (It finally and all-at-once courses through her cancer diagnosis essay.)

It is nearly always in the last paragraphs that Diski reveals her nuggets of truth, fully divulging her cold way of seeing, and naming the thing which she has spent pages describing. “Not Enjoying Herself” draws to a close with an acknowledgment latent throughout the essays: “I have a petty and annoying habit of wondering where writers of biographies get their information from.” Concluding “Stinking Rich,” she suggests that “Richard Branson sits in the soggy parts of our minds that represents the possibility of our dreams coming true and not having to despise ourselves.” Her wisdom is laid bare in “A Diagnosis.” When her mentor Doris Lessing suggests that she simply write about her childhood, Diski states: “I was enough of a writer to know that writing the story of my interesting childhood was not being a writer.” Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told? proves that Jenny Diski knew how to name things.