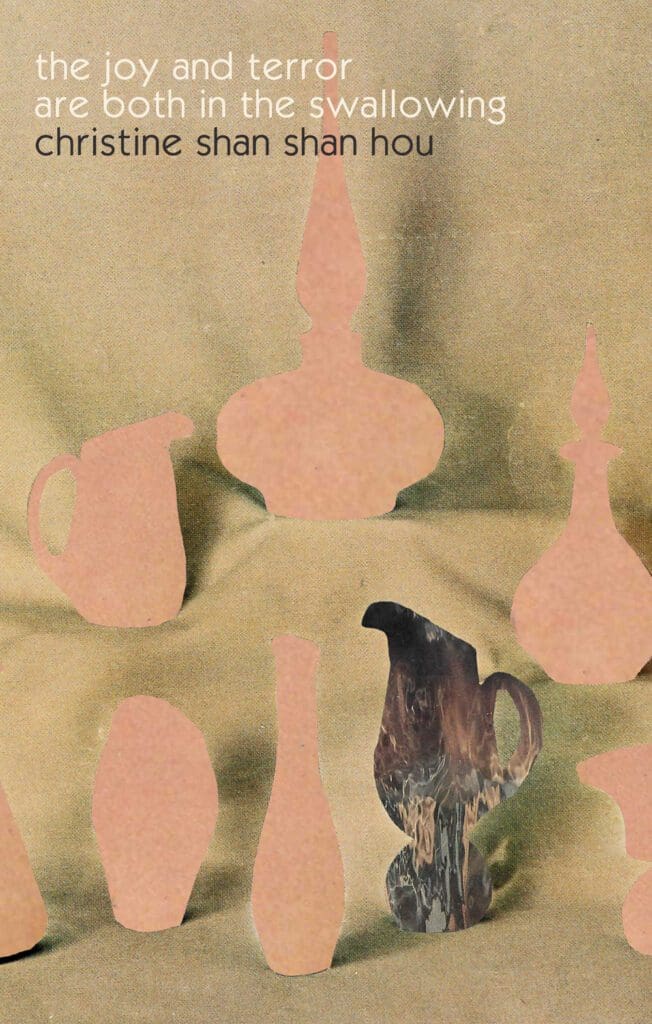

Christine Shan Shan Hou’s poetry collection The Joy and Terror are Both in the Swallowing (92 pages; After Hours Editions) takes its title from a quote by American photographer Diane Arbus. It was a time when Arbus’ marriage was failing—a time when, as Anthony Lane writes in The New Yorker, she “was, like her mother before her, dragged into depression and sucked down, declaring, ‘The thing that sticks most in the throat and hurts the most is how easy it is. The joy and terror are both in the swallowing.’”

Ten years later, in 1970, Arbus took a portrait of a sword swallower. The portrait shows a woman standing behind a carnival tent, her arms outstretched like a crucifix, her head tilted back, and the blade and hilt of a sword blooming out of her mouth. The sword points toward the sky, perfectly straight. Indeed, when we look at this image, what “sticks most” in the mind is “how easy it is”—how effortless.

In this way, The Joy and Terror are Both in the Swallowing is a sword down the throat, too. Hou’s language is precise, confident, and sometimes even steely, reaching immediately to the heart of things. Yet the range of images, ideas, and emotions throughout this collection make it anything but easy to stomach. With themes of nature, artificiality, lostness, and science, Hou crafts a landscape of language and being that is at once embodied and alienating, human and not. We are entering a new urban ecology: “a smooth era / what a smooth & / violent era.”

Part of what makes Arbus’ photograph of the sword swallower so startling is that we witness the astonishing verticality of the sword being contained within the fleshy, vulnerable human esophagus. This echoes Hou’s search for signs of life within formal and thematic rigidity. Throughout The Joy and Terror, her poetic voice strives “to feel my organs labor inside / their cardboard boxes,” to feel the heart beating within its cage.

As a result, Hou’s poemsare sparse and direct, as if trying to break through the smoothness. Many are splintered into stanzas that are only one or two lines. Pieces like “Soft Pornography,” “A Piece of Evidence,” and “Trust Exercise” feel sharp, each line being only a phrase or a few fragmented words. These sudden and disparate images bring surprise—they jolt us awake from our synthetic reality:

I pretend I am

in an office cubicle

Directly beneath

the sun

The cubicle sits

atop a pyramid

which sits atop a lake.

The coolness in Hou’s words and world perhaps comes from her desire to find truth hidden in the artificial ecology of city life. In the poem “Distant Relative,” she asks, “What will it take to convince you I am a woman of science?” It would seem that the entirety of this collection is an extension of this single question, for the work Hou undertakes in The Joy and Terror is that of an empiricist attempting to derive truth from a close observation of the world. “I am wide awake,” Hou writes. “How magnificently clear is the day.”

But this is not traditional science: this is poetry. Hou suggests that there is a difference. She writes in “New Age Expedition” that “Empirical data insists on offering something / that wasn’t even theirs to begin with.” With the pronoun theirs, Hou separates herself from the empiricists: this is not her, or even our, method. Whereas science often forgets that its practitioners are, like any human being, fallible, the poet recognizes her subjectivity and utilizes it to her advantage. In the poem “Heaven,” Hou writes,

I mourn the loss of small worlds while observing roaring rivers

I wonder what it feels like to be elderly

I am disappointed in the parts of my body that ache

I succumb to a fugue state

Within these lines, the elements of scientific inquiry—wondering, observing—are inextricably linked to pathos—aging, mourning, and disappointment. The speaker uses her small self to illuminate the broader human condition.

And through this inquiry, the speaker discovers herself confined to the failings of her own body. She is prone to stagnancy and repetition: “I succumb to a fugue state.” But just as the form of the fugue finds innovation in its stringent structures, Hou finds beauty in the confines of those “cardboard boxes” that make up the poems of The Joy and Terror. Her “Lost Haikus,” interspersed throughout the book, are neatly packaged pockets of light. Hou shows that she can make do with less. One stroke of the sword is enough.

In a world of misinformation, artificiality, and excess, Hou suggests that these small points of lucidity and feeling offer ways that we can stay “wide awake” to our surroundings and to our bodies. If ever we find ourselves lost in this deadly metropolis of modernity, Hou reassures us that sometimes all we need in order to orient ourselves is a sharp inhale. A haiku titled “Pause” concurs: “Inside a city / there will always be spaces / to breathe in between.”

One thought on “‘The Joy and the Terror Are Both in the Swallowing’ by Christine Shan Shan Hou: A Sword Down the Throat”