At the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, you can see a picture frame with nothing in it. The frame is nice enough: gold and engraved, waiting in a light-filled room on the second floor of the gallery. In this spot, in 1990, two men smashed the glass of Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee before cutting the canvas out of its stretcher and leaving with the stolen work in tow. The painting hasn’t been seen since. Still, the museum keeps the frame hanging: a symbol of its awaited return.

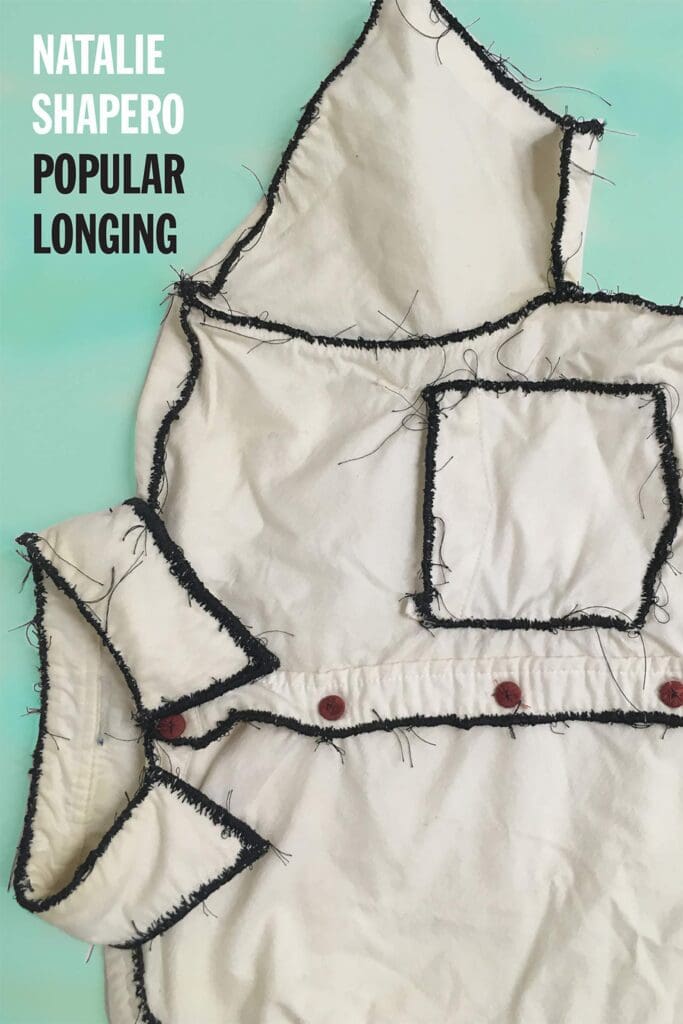

In the longest poem in Popular Longing, the third poetry collection from Natalie Shapero (69 pages; Copper Canyon Press), an echo of that frame appears. “Some museums get famous for having been robbed,” she pauses to remark, and “include with their / twenty-dollar ticket an exhibit of the empty frames.” With these lines, Shapero lends us a way of understanding Popular Longing itself: a series of intricate poetic frames that reveal, through spotless deadpan delivery, the absences with which we live. Keep an eye on what’s not there, these poems insist, just as much as what is.

It’s true: a lot is there. An itemized catalogue of Popular Longing would include rats and fortune tellers, party balloons and pearl-trimmed gems, Hell and California (and tattoos, and suicide notes, and dogs, and bumper stickers, and comets, and—). Shapero’s poetics are those of compulsive association, allowing her to land vast, connective leaps in just a few lines. In “Green,” we begin with an image of Cleopatra, before turning to the speaker’s workplace, followed by a remembrance of California—“when L and I hiked out to the obverse / side of the Hollywood sign”—and end with the thought of her deceased friend as a child.

Memory is the primary motor of these horizontal movements. It’s a tactic Shapero refined in her second collection, 2017’s Hard Child, which had as its epigraph a quote from Cees Nooteboom: “Memory is like a dog that lies down where it pleases.” The ensuing poems agreed, capturing recollection as wandering and restless, always just outside the limits of one’s control.

In Popular Longing, Shapero’s speaker is still burdened with the task of remembering. These poems tend to veer from a present image—“the salt-bitten building / where [she] used to live”—to the memories it surfaces: “the insolent / kitchen,” “the stink of shots / at a late hour.” Memory, here, is both companion and adversary, at once the agent that guides our speaker’s thoughts and the obstacle she seeks to avoid. “I’m ready to stop remembering,” Shapero writes in “Fake Sick.” “The trouble is / there’s nobody else who can do it.”

People often refer to Shapero as a comedic poet, one who is quick to use the set-ups and cadences of joketelling in service of her enjambed punchlines. What was fairly called “dark humor” across her earlier collections has been become even more grim in Popular Longing. A description of death, which closes the book, reads like this:

the whole of the globe turning

off for a moment, then shuddering

back, the same as it was,

except one person short.

And then before long, an utter new

person is born. Somebody worse.

The deaths—as well as the losses, as well as the brutalities—are numerous, peering out from line-break after line-break. “There’s so much violence, always,” Shapero writes in “Some Toxin.” There’s the vigil for a friend, T., in that old apartment. There’s a sudden fall, twenty-two stories from a downtown tower. There’s “the war.” Damage is received, too, by objects (mostly, paintings). In “Don’t Spend It All In One Place,” Shapero lists an “acid splatter across the Dutch nude,” a “hammer to the arm / of the PIETÀ,” a “man who drew his gun / and shot up a wall of old masters and then himself.”

Poetry holds a well-documented relationship with absence—its lines worn away by the blank space of the page—and, in Popular Longing, Shapero drives the medium even further towards loss. Some works are scoured of all punctuation. Several others end abruptly with an em-dash, like a microphone abruptly cut off. “I’m angling / to remain in this life as long as I can,” Shapero hurries to tell us in “Man at His Bath,” “being almost / certain, as I am, what’s after—”

What’s after? Where does something go when it goes? Shapero wants to know, and Popular Longing chronicles the infinite ways we make sense of loss, or fail to—through funerals and burials, cremation and re-incarnation, an exhibit of empty frames left waiting on the wall.