Sex in literature is the backdrop of the volta, of awakening. Sex represents the moment in which the character most deeply occupies their body, is most aware of their being, whether the experience incites joy or regret. But for all of the artful depictions of sex present in contemporary literature and other media, sexual kink has been largely neglected. The few representations of kink that do exist have assumed an exoticizing, alienating gaze, framing kink as something to be gawked at, commodified, rather than experienced.

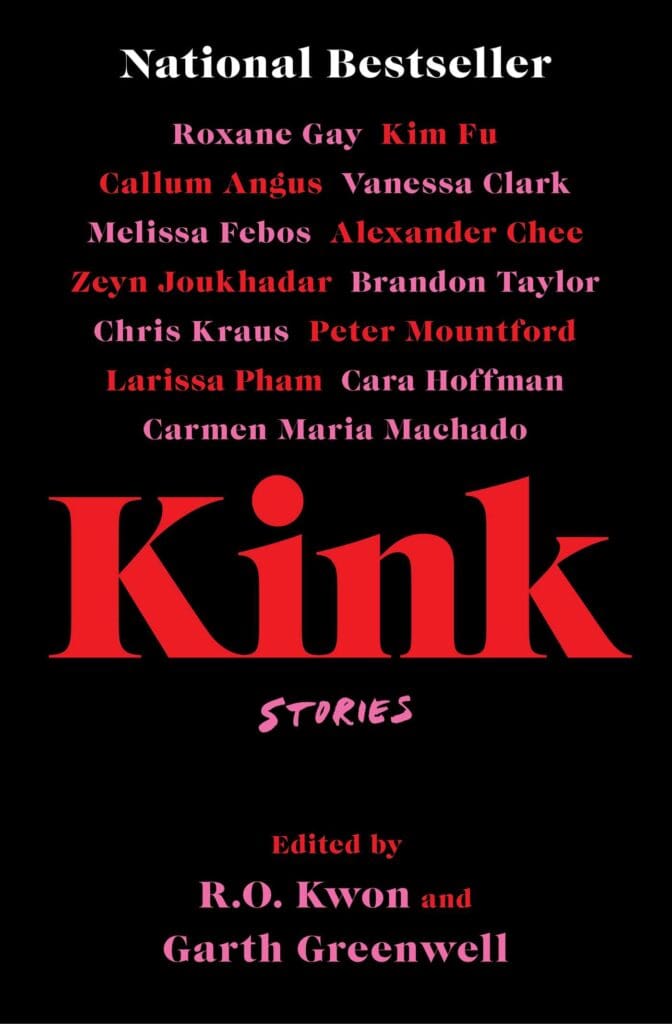

Editors R.O. Kwon, author of The Incendiaries, and Garth Greenwell, who released his novel Cleanness to great acclaim last year, have come to dispel misconceptions of kink through their anthology Kink: Stories. The pair have compiled an impressive collection of short stories that render kink with precision and compassion, displaying the intensity of the human experience through lesser-represented forms of sex. Kwon and Greenwell are accompanied by an ensemble of excellent writers, including Carmen Maria Machado, Brandon Taylor, and Roxanne Gay, among others. Each story in the anthology fuses the beauty of language with the visceral nature of sexual kink, yielding an engaging, complex portrait of kink and those who have found meaning in it.

We talked about the anthology with Kwon and Kim Fu, who contributed her story “Scissors” to the book. The interview has been edited for lengthy and clarity.

ZYZZYVA: Kink: Stories depicts sexual kink in a complex and compassionate way. What effect do you hope this anthology will have on readers who are unfamiliar with kink?

R.O. Kwon: One of my greatest hopes with this anthology was to push back against dominant narratives about what kink is. I’m so used to serial killers also being kinky in books, movies, and TV shows, that I play a game, you know? Once there’s a serial killer, I’m like, “Okay, how many minutes until we learn that they’re also kinky?”

And, of course, the other stereotype is the emotionally stunted, kinky billionaire running around. It’s like, this is such an unappealing group of people! Serial killers and billionaires? For the love of God. I hope very much that this book will push back against these narratives and make it less possible for such narratives to exist. It just seems extra wild to me because—again it’s hard to generalize since kink is such a vast thing—consent is centered and foregrounded in a lot of kinky accounts and encounters, so much more so than in other sexual encounters.

Z: The stories that comprise Kink are incredibly diverse both in terms of content and style. What was the process of compiling such a wide-ranging anthology?

RK: What Garth Greenwell and I realized early on as we started talking about the book was that it was of central importance to us that we not ever really define “kink.” We thought quite a bit about how to solicit work from people, and the phrasing we settled on was: “Would you be interested in writing a story that engages meaningfully in some way with ‘kink’ as you define it?” The last thing we wanted to do was any sort of gatekeeping.

It was also of great importance to me that the book be as inclusive as possible. Of course, it’s only one book, and there are limitations to what you can do with fifteen stories. But if I’m spearheading something, it’s important to me that there be more queer people than not. That there be more people of color than not. That there be more marginalized genders than not.

Z: Were there any challenges or considerations you faced in depicting kinky (or otherwise) sexual dynamics in your story “Safeword”?

RK: I’m so thoroughly on the side of openness and the freedom to want what you want and for your body to do what it wants to do. That said, I am not free—I myself am in no way free. So I’m working on it. Something that helps me greatly in writing something like “Safeword,” something where it feels extra hard sometimes because it’s wrapped up in my own tangles of shame and wanting to hide, is telling myself, “It’s totally fine. No one has to see it. No one’s gonna read this.” I say that to myself out loud, over and over again, and it has a strong calming effect.

Z: Kim, what about the challenges in your story “Scissors”?

Kim Fu: In a culture that focuses so much on productivity, there’s this idea that physical pleasure and self-knowledge are frivolous in some way, or immature, or a waste of time. I think a lot of people see it as self-indulgent and juvenile. And it isn’t, especially right now, when—I think—most people live online, and we’re further away than ever from our bodies and our experiences of ourselves as physical beings. That this book is coming out right now is really valuable to me. It’s encouraging people to inhabit, think about, and value their bodies in a way that we don’t in the dominant culture that I see.

Z: Kim, the dynamic between Dee and El in “Scissors” is fascinating—it seems to be a relationship predicated almost entirely on the potential for a breach of trust. What did you have in mind while depicting this dynamic?

KF: The idea that seemed scariest to me was trying to write something that was celebratory or genuinely, un-ironically, sincerely supposed to be erotic. I had this weird sort of stigma inside, where I felt like—bad sex, you’re allowed to interrogate for twenty pages. Good sex, you’re allowed one lyrical sentence.

It just sounded so scary to me, to write something that was supposed to be sexy and a positive experience, where the tension of the story came from the game the characters were playing. It made me feel vulnerable, like I’d be opening myself up to ridicule in a way I wouldn’t feel if I were writing about broader interpersonal conflict. And a lot of the stories in the collection do that really beautifully. But because I found that so uniquely terrifying, that felt to me like, “That’s probably what I should do, then.” I think if something’s scaring me that much, then it’s probably worth looking at and exploring.

So, I did really want to write a story where they’re having fun. They’re having fun and they’re enjoying each other and it’s built on this trust. The tension is fun for them. One of the great things about Kink are these safe boundaries. I wanted the reader to experience that thrill and also the safety that came from that trust at the same time.

Z: There’s this beautiful line in the introduction of Kink that discusses how one’s body is inseparable from one’s experience. Can you elaborate upon the synonymous nature of the body and experience as it manifests in Kink?

RK: My understanding of my characters’ bodies is absolutely at the core of my understanding of writing fiction. I worked on my first novel, The Incendiaries, for ten years, and there was so much I wrote and threw away. I cut a 100-page section that took place in 1970s Korea. I wrote it, and I really worked on it, but in the end I threw it away because I realized I could not get close enough to what it felt like to be a body in 1970s South Korea: I wasn’t alive, I didn’t even have the knowledge in my body of what would have been happening in the U.S. at that time. As much as I tried to watch movies and listen to music from the time, I couldn’t do it. What it would feel like walking down that street that I’m imagining. What exactly are the noises? What’s playing on the radio? I had none of it. And I realized that meant for me that I probably am never going to write historical fiction—I need to be able to imagine what it’s like to be a body in a scene, however I imagine that scene.

I always tell writing students that one of the most reliable ways to move forward when I have no idea what’s going on in a scene and everything feels hopeless, and I’m asking why I didn’t just become a dermatologist—in those moments, it really helps me to forcibly eject myself out of my body and into the character’s body. What are they feeling, hearing, touching? Are they thirsty? Does their leg hurt? It almost never fails me. That leads to something.

KF: I agree with what Reese said so much. That is totally central to my understanding of fiction, too, that you’re writing a sensory experience of a body a lot of the time, and that is also something that I find myself saying to writing students a lot. I have a student right now who’s writing a scenario where a character is feeling two conflicting things, and she’s having trouble not just writing over and over again the character thinking, “I feel this way, but I also feel this way.” What we ended up talking about was how those two feelings manifest physically, that your body can be doing things while your mind is another. And that was a way of representing conflict—her eyes are being drawn a certain way, certain things make her pulse speed up, or she notices particular things. Certain physical details of her surroundings stick with her even if she wants to think or feel something else. That is so core to fiction.

The first line in “Scissors” mentions the smell of dust burning on stage lights. That detail was what got me into that story. I remember having this abstract premise, and I couldn’t get into the scene until I could smell the dust burning on the lights, and then I thought, “Okay, now I’m there, now I can write this.”

Z: There are certain stories in Kink that I felt were more subtle and restrained. Some of these stories may not appear overtly “kinky.” How do you situate them within this greater narrative of kink, among other pieces that depict more unconventional dynamics or acts?

RK: One of the things Garth and I are most excited about with this anthology is just how vast of an array of stories is in these pages. I already talked about how important inclusivity was, but also the aesthetic diversity—it makes us really excited. I think with an anthology like this, especially an anthology where, as far as we know, there hasn’t been another quite like it in a really long time, it feels important for there to be as wide a span of experiences as possible. People have asked, “Well okay, you don’t want to define ‘kink’ for the book, but what is it for you?” I think one possible way to begin to gesture toward a definition of kink might be that kink tends to be more open to more ideas of what sex can be.

Z: Going forward, do you see kink playing a greater role in literary fiction?

KF: Using kink as an acknowledgement of how vast and varied the human experience of sexuality can be—I think it fits into a larger movement of just a greater range of human experience in general being given serious literary attention. I hope those things are tied together.

RK: I have trouble using the term “literary fiction,” but there’s not a better term—we lack terms! The best way I can define literary fiction, or the fiction I’m writing, the fiction I’m most interested in and where I come most alive, where it feels like the temple I serve, is writing that is at least as obsessed with language and humanity as it is with anything else. That is primary to me, rather than anything else. One of my first hopes in putting together a book like this was that I wanted to have these experiences that I hadn’t seen very much of in the kind of writing that I most love to read.