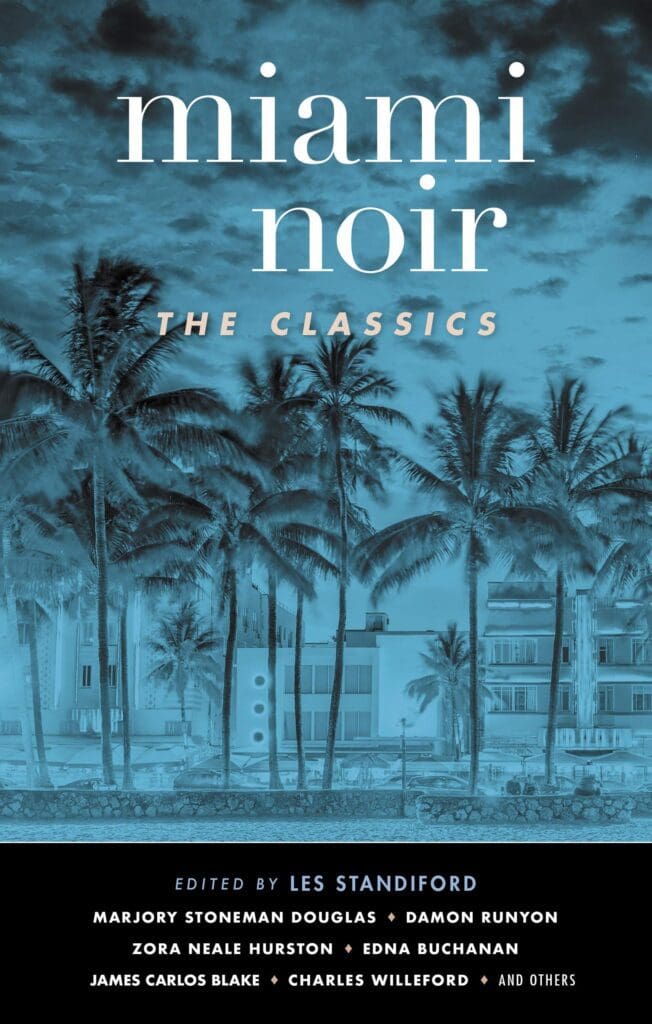

According to historian Paul George, Miami was first called the Magic City in the early twentieth century, not because of its beautiful sunsets and glistening waters, but to lure northerners to the humid, mosquito-filled swampland. “Like many Florida stories,” Connie Ogle once reflected in the Miami Herald, “there may have been a bit of a swindle involved.” Miami, like any paradise, often produces stories where the magical setting clashes against the more dubious characters within it. This tradition is displayed most recently in Miami Noir: The Classics (Akashic Books; 397 pages; edited by Les Standiford).

Featuring 19 stories published between 1925 and 2006, Miami Noir: The Classics is the latest in Akashic’s prolific, award-winning noir anthologies. (The publisher’s other collections spotlighting various cities have been edited by Joyce Carol Oates, Tayari Jones, Edwidge Danticat, among others.) The follow-up to 2006’s Miami Noir, this wide-ranging selection includes mystery, revenge, gumshoes, and gunplay. Certain stories experiment with form, others with plot, but in all, according to editor Les Standiford, “calamity takes place against the backdrop of paradise.”

The early stories are arguably the most exciting, regionally and artistically. An excerpt from Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) stands out from the rest. Both local and existential, Hurston writes bravely, often mysteriously. “It was the meanest moment of eternity,” she declares in the climactic scene. “Then the grief of outer darkness descended.” Another story, “Pineland” (1925), is an O’Connor-esque entry by famed conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas. In it, the landscape becomes its own eerie character:

Every tree held its own twist and pattern; every tree, even to the distant intermingled brown of trunks too far away to distinguish, was infinitely itself. Sometimes the pine woods came so near the road he could smell their sunny resinous breath. Sometimes they retreated like a long, smoky, green-frothed wall beyond house lots and grapefruit groves or open swales of sawgrass or beyond cleared fields where raw stumps of those already destroyed stood amid the blackness of a recent burning. Against the horizon their ranks rushed cometlike and immobile into the untouched west. He felt the comprehension of them growing upon him—the silence of their trunks, the loveliness of their tossed branches, the virginity of their hushed places, in retreat before the surfaced roads and filling stations, the barbecue stands and signboards of the new Florida.

The rich, sultry landscape runs aground in “the new Florida”—not unlike the rest of the collection. By structuring the book according to time and place, Standiford invites readers to track the setting as it shifts story-by-story.

The landscape recedes, the tempo picks up, the language adjusts. As we move through the ’70s and into the ’90s, the prose becomes less sumptuous and more like the pulpy prose one might expect from classic noir. “Guys” continually grin, quip, and use “real” as an adverb, such as in the brassy tenor of best-selling novelists like Carl Hiaasen (also a Miami Herald columnist. Hiaasen is not featured in this collection, though Standiford mentions his work in the introduction). In Standiford’s own story, the fantastical “Tahiti Junk Shop” (1999), someone’s hand is described as a paw, fittingly, since there is an animal quality coursing from one page to the next.

In these stories, you might find yourself at a dog track, a gas station, or a hotel. When, during a holdup, someone chokes on a sandwich, we learn that “in Florida if somebody dies for any reason in a felony it’s murder.” So in a moment of surprising humanity, the armed robbers in James Carlos Blake’s “Small Times” (1991) begin to perform the Heimlich. In “To Go” (1996), Lynne Barrett plays with structure, cutting up paragraphs to convey a deeper brokenness. Of the pure “noir” form, an excellent example is Lester Dent’s lengthy “Luck” (1936), which demonstrates clean prose and keen observation, along with a swiftly developing plot.

While travel remains restricted due to COVID-19, Miami Noir: The Classics dares readers to explore a geography that may be both unfamiliar and unsettling. If the prose is not always pristine, the setting nonetheless proves as tangible as if you were there, muggy air rising off every page.