“It’s okay to be white,” reads the sign posted in November by the Social Work building on the University of Utah campus where I teach. White poster, fine black letters in Arial font. The sign disappears in a day, though photos are taken, passed via social media. Two posters with the slogan “Stop the Rapes, Stop the Crime, Stop the Murder, Stop the Blacks” are then taped up, each with a web address for the manifesto “Blood and Soil” written by Vanguard America. These, too, are torn down. Someone spray-paints racist epithets on a campus construction site. This is not the first time signs like this have appeared at my university, but it is the first time so many have come in such quick, relentless succession. People chart the rise of these signs against the presidential inauguration. The signs, we tell ourselves, represent a dividing line—the campus we had before the current president, the campus we have now. This, however, is only our imagination of them. In reality, it is hard to point to any one dividing line.

The anxiety is that the language has been generated by one of our students, though of course such language has been appearing across campuses around the nation, which makes us both less and more relieved. We are not the writers but the written upon. Disembodied, or so multiple-bodied, this language becomes emptied of meaning. The language cannot embody, we say, because this speech—so formulaic, so anonymous—is ultimately addressed into the void.

But, of course, the language does embody. The language was always there, not spray-painted or posted but uncovered. The language embodies because language is always speech addressed into the void into which someone, willingly or unwillingly, steps. The language opens up another dimension of the campus: a door which was once closed, and now remains open. Less than a month after Klansmen march in Charlottesville, killing a young white female protestor with a car, weeks after the president, to nearly everyone’s disbelief, says about this event, “There are very fine people on both sides,” Ben Shapiro, a conservative and racial provocateur, comes to speak at my campus.

The language embodies because I am repelled by and called to this sign. I am half-white: I know what the sign means, though I am also mystified by it. What, in this context, does the author mean by “be white”? A small, real warmth in the belly: some spark of recognition at the sign’s dismissal of racial guilt, this spark quickly extinguished by disgust for the self-pity the sign suggests by its inability to think about anything but the priority of its condition. Sensing that “doubling of time” that the poet Lisa Robertson argues is the condition of reading, I, too, am doubled in time and meaning before the sign. I am and am not the audience for it. Unable to look away, unable to dismiss it, and on both sides, outrage.

I am thinking about this sign because I am thinking about Paul Klee, trying to parse the monumentality of his painting Cathedral for a lecture on Klee I’m supposed to give at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Cathedral’s monumentality is actually a trick of the eye: the painting itself is only 11 3/4 by 13 7/8 inches, the length of a poster. Many of Klee’s works are modest in size, the canvases bits of cardboard pasted to wood, sometimes scraps of canvas and other leftover materials. This thrift, I learn during my research on Klee, was perhaps the result of Klee’s time as a soldier in the German army, when such materials were rationed. When Klee discovered a German plane crashed in a field, cleared of its bodies, he rushed to cut off pieces of the precious linen with which the plane had been covered. He saved everything, his son, Felix, said, and even painted on the backs of other paintings. Klee, according to all who knew him, refused to waste anything.

Cathedral’s immensity is thus due to its visual complexity. The canvas is a series of crude white lines assembled into doors and lintels, arches, windows, rooflines, walkways, buildings upon buildings. The cathedral itself is an architectural outline ghosting a soft spatter of pastels: pink and green and yellow and pale red. Cathedral marries Klee’s background in graphic design with painting, practices which Klee did not see or treat as distinct, much as he did not see any distinction between visual and textual art. Both, he said, were problems of time and space: problems inherent to our general practices of reading.

To see Cathedral then is to read Cathedral; to see the painting, I have to learn how to read Klee. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I study his painting Oriental Garden for an hour, trying to parse his lines, until I realize that none of these lines suggest or even work in the same spatial dimension. Is the path between the garden plots he’s drawn in front of or below the little buildings? Am I looking down at the garden he’s envisioned or straight at it? His doors—crude black squares scribbled onto canvas—look like entrances at first, but begin to suggest broken lintels, headstones. I feel nauseous looking at the painting. The lines radiate out, intersecting only where I must imagine the two-dimensional and three-dimensional meeting. Looking at Klee’s lines, I don’t know where I am meant to stand; I cannot tell which dimension he wants me in. I read but can’t quite follow. He writes and I struggle to read him. I almost read him. Which is to say perhaps I do not read him at all.

The pleasure in Klee’s paintings is that I can stand anywhere. Which is also what makes Klee, at times, terrifying to me.

The 18th-century art critic Gotthold Lessing, whom Klee studied, argued that space and time are progressive: action unfolds, allows for causality, even contradiction. Painting, unlike poetry, must compress time. Its uniformity means details and action are suppressed and elided so that we can take in multiple images within the same moment. What Klee achieves as a painter is something like poetry’s unfolding of time: the door opening and closing at once. The garden both above and below-ground. I see all actions stilled at the same moment, and yet by being aware of the different ways of entering and following his lines, I also create progressive action. Unlike Lessing, Klee insisted that space was the truly temporal concept: it is not the depiction of time’s accrual and diminishment, the body in motion that mattered, but the “process of beholding” that takes place over days. Time is not depicted so much as enacted by the viewer. To see Klee, I must read his painting as a lyric unfolding.

There is, too, a sense of progressive time at play in the racist sign. Reading it, I cross over from one consciousness to the next, from the woman who is “not” raced to the one who “is.” The sign is permanent disorientation, though not pleasurable in the ways that Klee’s disorientations are. I suspect few people would find racist language pleasurable based on how it reorients them in relationship to the speaker: either I am in this body with this speaker or I am in another body against the speaker. In either case, such language is meant to make one’s relationship to the world clearer. This, I realize, has never been the case for me.

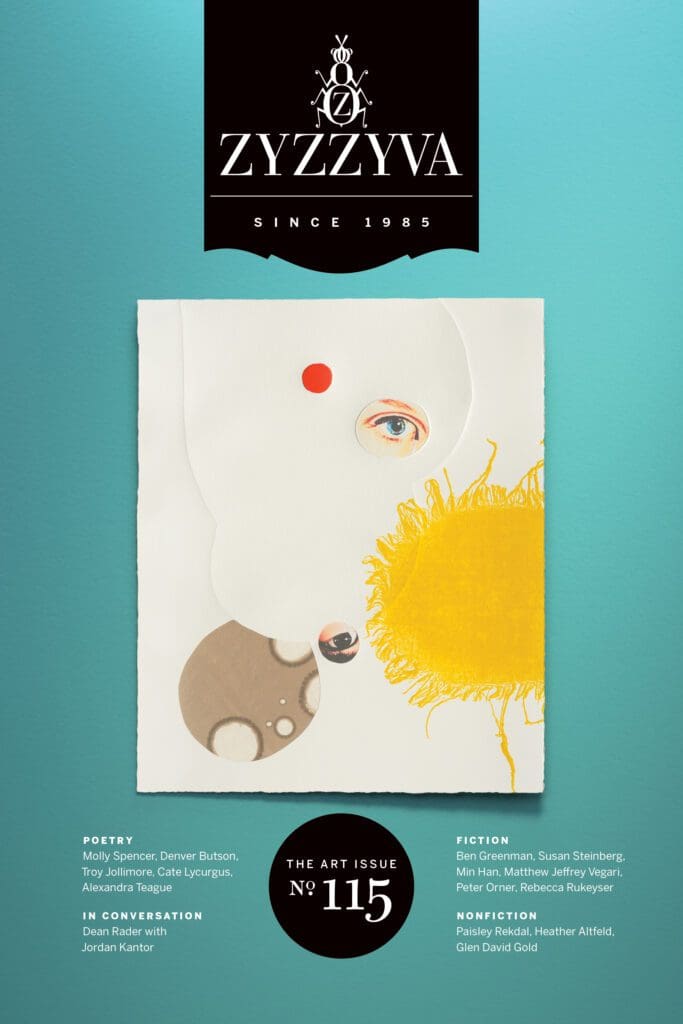

You can read the rest of “Cathedral: Some Marginalia on Reading” in our Art Issue. Order a copy here.