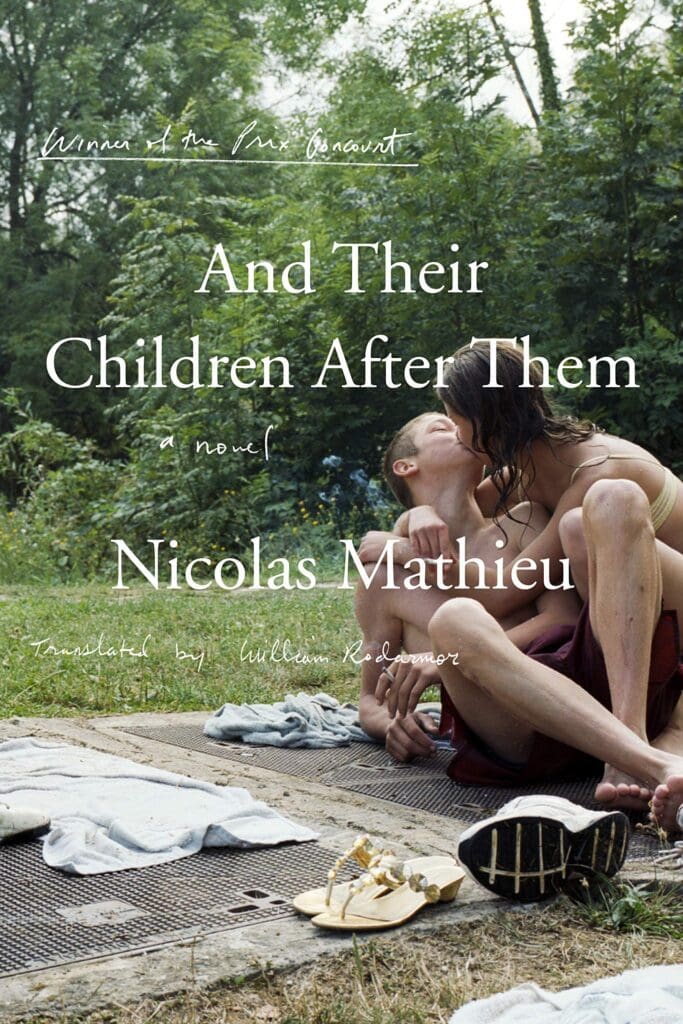

Recounting four summers in the life of a teenager, Nicolas Mathieu’s new novel, And Their Children After Them (420 pages; Other Press; translated by William Rodarmor), is a testament to what words can do at their leanest. The opening reads as check list: “Anthony had just turned fourteen…His parents were jerks. When school started he would be in ninth grade.” When Anthony and his cousin (never named) are “bored out of their skulls,” they paddle over to a nude beach where they find not nudists, but peers, girls their own age—and yes, out of their league. The novel proceeds in teenage-like prose: disaffected, clipped, effortless. At the beach Anthony “was scared; it felt great.” And a few pages later: “He was suffering; it felt good.”

And Their Children After Them takes place in a fictional, post-industrial valley in France. In the background, old mills disintegrate, furnaces shut down. The stalled economy reflects the characters’ malaise. Repeatedly they ask, “So what are we doing?” or some version thereof. “It was the ritual question, the same one asked ten times a day.” The more it’s asked, the more evident it becomes there is no answer. Anthony and his friends remain suspended not just in boredom but immobility: there’s nothing to be done, nowhere to go, except forward in time. To what little mobility they have, they ascribe great significance:

Life here was a matter of trips. You went to school, to see your friends, to town, to the beach, to smoke a joint behind the pool, to meet somebody in the little park. It was all comings and goings. Same for the adults: to work, to run errands, to the babysitter’s, to Midas for a tune-up, to the movies. Each desire implied a distance; each pleasure required fuel. People wound up thinking of the place as a road map. Memories were necessarily geographical.

Mathieu writes with an adept omniscience, making hairpin turns into various perspectives from paragraph to paragraph. Anthony’s parents struggle matter-of-factly with alcoholism and unemployment. “Anthony looked at his dad. He had the face of a tired man who drank too much and slept badly. It was as deceptive as the sea. A face he loved.” Alongside the hard facts, a beauty emerges, because love is also a hard fact. Particularly heartfelt are the evenings Anthony spends with his aunts and cousins:

The dinners would last until well past midnight, and Anthony always wound up falling asleep on the sofa, lulled by the grown-ups’ talk. … The smell of Gauloises, the men picking tobacco from the tips of their tongues. The knock-knock jokes. The women chatting in the kitchen. The coffee maker burbling at one o’clock in the morning. His father’s arms as he carried him to bed.

The jumps in chronology—two years between each section—help create a sense of the inevitability of time. Characters grow up just as we begin to know them. A drug runner finds himself pleasantly domesticated, settled down with a child. Even so, “Life wasn’t enough for him, and the baby didn’t change anything. To the contrary. Well, it was more complicated than that. He couldn’t have said how.”

Hot and hazy, And Their Children After Them, which won France’s prestigious Prix Goncourt, is a deft work of nostalgia, well-suited for this summer season. It calls to mind those little-appreciated moments when one might brush shoulders with a stranger. The book’s most significant occurrences take place in public—at a beach, a bar, a Bastille Day celebration, a bistro where the World Cup is playing. People are smoking, music is playing. You excuse yourself to get some air, and never know who you might run into: a face from the past whom you might remember, or who might remember you.

“Bored out of their skulls”. Really? That is so tired. Such a cliche’.