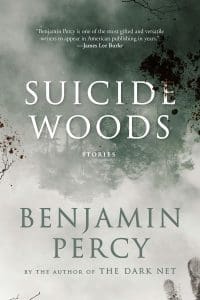

Benjamin Percy is a writer who understands that, in the twenty-first century, the scariest thing to many readers is not the supernatural or threats from beyond the grave, but something altogether closer to home: real estate. His latest release, Suicide Woods (192 pages; Graywolf Press), collects a variety of stories culled from the last decade of Percy’s career. The book covers a number of subjects and genres, including the uncanny, from “The Dummy’s” tale of a wrestling practice dummy that may or may not be imbued with life, to the titular story’s account of a group of depressed individuals who venture into a Japanese-style “suicide forest” in Oregon’s Tualatin Mountains to remind themselves of the sanctity of life. But arguably the most effective stories in the book tackle the everyday anxiety and possessiveness many Americans experience over their property. Home is, after all, where one is supposed to feel the safest, the most at ease—this remains true even in our era of rising rent prices and widespread gentrification.

In “Dial Tone,” a telemarketer loses his grip on sanity as he continually deals with justifiably irritated people:

To understand a story like this you would have to know what it’s like to speak into a headset all day, reading from a script you don’t believe in, conversing with bodiless voices that snarl with hatred, voices that want to claw out your eyes and scissor off your tongue. Do you know what that does to a person? Listening to people scream at me and hang up on me, day after day, with no relief except for the occasional coffee break…?

In “Suspect Zero,” a small town is rocked by a series of increasingly bizarre crimes. One of the most unsettling scenes depicts an older couple returning from a European vacation only to be struck by the unease of thinking someone has been inside their house while they were away, shattering their illusion of sanctuary. When the Templetons call the police, the officers who arrive on the scene matter-of-factly explain how professional burglars will case a neighborhood, looking for any sign of opportunity:

They often begin with the phone book, making note of all the doctors, dentists, lawyers, accountants, veterinarians in an area. Even if their home address isn’t in the white pages, the deep Web has crawlers that can help. From there they go online and study social media accounts. Usually someone was on vacation, posting photos of a pig roast in Hawaii or a white-humped mogul field in Colorado.

The powerful “Writs of Possession” looks at the housing crisis from a number of angles, told in a series of vignettes that most often return to Sammy, a woman with an unenviable task in the Sheriff’s office: she must deliver eviction notices to tenant’s doorsteps.

She supposes she feels bad for people when they cry or beg or point to their grubby children and say, You’re doing this to them. Maybe she pities them—that’s a better way of putting it…when people show their teeth or kick over chairs or get down on their knees and take her hand and beg, she simply says, “I’m no judge, no jury,” so that people contain their anger and sadness, bottle it up for someone else.

Over the course of the story, we see a group of squatters who do their best to remain undetected while living in the basements of otherwise occupied homes (the thought of someone living unnoticed in one’s own home, also seen in this year’s breakout film Parasite, is yet another idea that punctures the safety we associate with our living space), as well as a group of neighbors who go to drastic, criminal measures to project the property values on their block.

Even in the novella-length “The Uncharted,” in which a group of explorers disappear in a remote religion of the Alaskan wildness, the tech-funded expedition feels in part driven by the capitalistic desire to chart and map every last corner of the earth, as though the species must commodity and ultimately sell every last parcel of land that remains unblemished by townhomes and big box stores.

Over the last decade, Percy has built a reputation as a writer who is as comfortable in the world of contemporary literary fiction as he is furthering the tradition of genre writers such as Ray Bradbury and Stephen King. His tale of apocalyptic contagion, “The Balloon,” included here, carries the influence of King’s The Stand, and was later expanded by Percy into his own novel The Dark Land. Percy’s strength as a writer rests in his ideas. Each of the pieces in Suicide Woods boasts at least one suggestion that lingers in the reader’s subconscious, whether it’s the child who returns seemingly from the dead but frozen alive in “The Cold Boy,” or the dirt-spawned being who gives his name to the story “The Mud Man.” None of these stories trade in shock value; Percy instead opts for atmosphere and character study over the violence or gore one might associate with the horror and crime genres.

Percy’s most strikingly drawn character in this collection must be “The Uncharted’s” aptly named YouTube daredevil Josh Wilde, who finds himself driven to tempt death for the cameras again and again due to his guilt over surviving the car wreck that claimed his family’s lives. Ultimately, Josh discovers a harsh lesson: that there are still some places on the planet that man was never meant to set foot.

The idea of such boundaries—of physical spaces that should or should not be trespassed, and the realization of our lack of ownership over the world around us—defines many of the stories in Suicide Woods. Man is no longer the master of all he surveys, but Benjamin Percy raises the chilling question if he ever was.