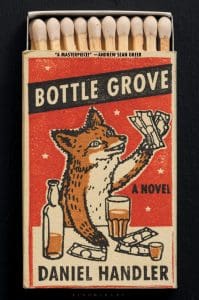

In Daniel Handler’s seventh novel, Bottle Grove (227 pages; Bloomsbury), which was published in the fall, San Francisco gets both a kiss on the cheek and a flick to the ear. For those who have lived in the city for two or more decades, the novel has a magnetism perhaps unfelt by others who’ve only known the place in its most recent incarnation—as that of a giant Lego set, one pulled apart and restacked according to the heedless whims of the tech industry. Handler, a longtime San Franciscan, evokes the city in its beloved pre-boom familiarity, but because he’s telling a contemporary story, it’s free of nostalgia.

The narrative, one of changing identities and shifting desires—both carnal and financial—among various men and women from different social strata (bartenders and moguls, the struggling and the ensconced), is pleasingly dream-like. The settings all suggest the “inner” neighborhoods of the Richmond and Sunset districts, those places where you can still hear the foghorns sound, and where the stands of trees and blustery gray weather supply its streets with an eternal quality, as if it were a place out of the mist, outside of time. (And years ago, a feeling only reinforced when waiting an eternity for a requested taxi to pick you up.) There’s a cozy quality to the book, too, with people ducking into bars to avoid the cold rain or much worse, and a strong sense of how disparate people so easily cross paths here. (San Francisco has been called an urban village for good reason.)

Via email, Handler, in his humorous fashion, talked to us about his latest novel, about identity and desire, and about the state of our city.

ZYZZYVA: The impossibilities and absurdities of marriage and coupling are a theme of Bottle Grove, and there’s an air of A Midsummer’s Night Dream to it. People unsure of who or what they want; people living as in a haze, and somewhat surprised with whom they finally wind up with. Could you talk about this particular lens—loopy, almost slapstick—in which the novel examines romantic love?

Daniel Handler: This was the tone I wanted throughout, both in examining how marriage changes and how a city changes. Quick, impulsive decisions you have to live with, influences that are difficult to trace but impossible to escape, waking up a changed person, in a changed environment, wondering exactly what the hell happened. This is why it made sense to structure it like a pop album: where something impulsive gets pinned down and recorded, and then means something different every time you listen.

Z: The characters in the novel, all to some degree, are protean. But that leads the reader to a wider consideration—why don’t we consider cities, despite the abundance of evidence for this, as shape-shifters themselves? It’s as with people, don’t you think? When they change seemingly abruptly it’s upsetting and confusing.

DH: With a city, we’re always wondering what we can change that still makes it the town we love. Is it still San Francisco without Lucca Ravioli, or the Sutro Baths? And yes, it’s something similar with people. Is my friend still the same friend if he becomes a father? An addict? Successful? Bottle Grove tries to expand these ideas into the melodramatic, the better to look at them more closely, I hope.

Z: Do you think it’s being able to see traces of what you knew—traits that sparked your love for a person or a place—amid newer perhaps unappealing details that alienate us from that person or place? Or is there something else going on? A reminder of how little we seemingly control about our lives?

DH: It is always bracing to be reminded we are not the hockey player, or even the stick; we are the puck. But the more you stay in a place, the more every square block, every eye’s view, has ghosts behind it. You end up like a car working for Google Earth, updating but never forgetting.

Z: I was struck by the sheer amount of drinking in the book. It’s copious and invites the reader into a demimonde that I find to be characteristically San Franciscan. That is, the many delicious dives that stretch across the city; that particular pastime of day drinking in North Beach or the Mission during the workweek. Or are those things anachronisms now?

DH: Surely they’re only as anachronistic as artists in San Francisco, which is to say, hunted to nearly extinction. But I think chemical influence on consciousness has a long history in all interesting places. And a good bar is still such a fascinating gathering place: regulars and tourists, the coupled and the lonely, people out for a good time and people out to escape a bad one—all kinds of overlaps that might not otherwise occur without liquid assistance.

Z: At the risk of further romanticizing an already romanticized city, do you think there’s something about the windy, foggy weather of San Francisco that makes those bars further alluring? I’m thinking here of the pubs you can find in the Richmond and Sunset districts, complete with fireplaces and backgammon boards. Interestingly, it’s the same sort of weather that makes one want to hunker down and read for hours.

DH: A friend and I are reading The Odyssey together, out loud, in different dive bars. What I love is not only all the bars—different but the same—sprinkled through the city, what I love is that our endeavor isn’t very different from everyone else’s singular missions. Everyone’s there for something.

Z: One of the ever-fascinating aspects of San Francisco is how many pockets of neighborhoods exist within its tight quarters; a stretch of street seemingly untouched by whatever giant transformations are underway. Bottle Grove evokes that cloistered coziness, I think. Was that your intention?

DH:Absolutely. All the unsung neighborhoods and their short blocks of little businesses.

Z: The novel would suggest that that very coziness—that sense of security in knowing you have a place you belong to—is being menaced, no?

DH: I think we’re in the process of learning if we’re really being menaced, or just feeling like it. But feeling like you’re being menaced, as with feeling like you’re in love or feeling like you’re thirsty, is kind of the same thing.

Z: Bottle Grove is full of many literary referents, and one of its delights is that you can be ignorant of all of them but still enjoy the novel. But could you tell us more about Reynard the Fox, for whom one of the characters is named? What drew you to employing such an ancient figure in your novel?

DH: I was just starting to think about this book when I spotted a fox in my neighborhood—a startling site that, along with coyotes, has since become commonplace. I started reading about foxes and saw that, unlike other animals, the fox is given the same personality all over the world: conniving, amoral, often in disguise. It was such a perfect spirit for what I was trying to capture, and before long I discovered Reynard the Fox, an old French text, alternately funny and terrifying, that often uses romantic love as a plot device to explore how little we know. It seemed fair to nick his name.

Z: What is your greatest trepidation about how San Francisco has changed in the past decade? And what has been an unexpected delight?

DH: The income inequality is the worst—forcing more and more interesting people out of the city and bringing in a sort of wealthy playground sort that’s really no fun.

On the plus side, though, you no longer have to rely on taxis to get home.