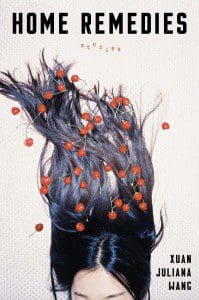

“Family,” “Love,” and “Time and Space” comprise the three sections of Xuan Juliana Wang’s first story collection, Home Remedies (204 pages; Hogarth). These categories describe this book better than much else could: Wang conjures an incredibly wide range of characters and plotlines, all tied together through notions of familial bonds, love, and temporality. There are no broad strokes or homogenizing glances in Wang’s work. These stories, concerned with Chinese young people and their engagements with culture, curiosity, and identity are complicated and specific, personal and detailed, messy and absurd. Each story Wang creates is so perfectly and wholly its own world; the only moment of disappointment they offer is in their brevity. It’s hard not to feel a sense of loss at the close of each universe, so vivid, full, and necessarily affecting.

“Family,” “Love,” and “Time and Space” comprise the three sections of Xuan Juliana Wang’s first story collection, Home Remedies (204 pages; Hogarth). These categories describe this book better than much else could: Wang conjures an incredibly wide range of characters and plotlines, all tied together through notions of familial bonds, love, and temporality. There are no broad strokes or homogenizing glances in Wang’s work. These stories, concerned with Chinese young people and their engagements with culture, curiosity, and identity are complicated and specific, personal and detailed, messy and absurd. Each story Wang creates is so perfectly and wholly its own world; the only moment of disappointment they offer is in their brevity. It’s hard not to feel a sense of loss at the close of each universe, so vivid, full, and necessarily affecting.

The book’s opening story, “Mott Street in July,” centers on a Chinese family living in the U.S. over the course of a very hot summer, one marked by the national “Asian carp crisis.” The three children of the family, Walnut, Pinetree, and Lucy, watch as their parents leave their small apartment to join the “Fish Generation,” those who presumably have gone to kill the carp, which “could be lured with moon cakes and rice noodles to swim alongside chartered boats across the ocean, back to the waters where the carp belonged… to guide them back to their rightful home.” Political and surreal, this story is as heartbreaking as it is subversive, able to touch upon intergenerational trauma, abandonment, and love under systematic exclusion through almost mythic prose:

The fish followed the river, the father followed the fish, the mother followed the father, and the children, holding their arms out, did not have a past to chase. Love could be a burden, too… The fish themselves must be confused, too. The carp hadn’t done anything wrong… They lived for more than a hundred years in these American waters and felt a lot of anguish and confusion, which they passed down to their own fish children… They had come so far and done what was asked of them; now they were unwanted.

“Days of Being Mild” (likely a reference to Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-wai’s 1990 film Days of Being Wild), by contrast, features a group of young people who have recently moved to Bejing, or Bei Piao, young adults out “to prove that the Chinese, too, can be decadent and reckless.” The group of roommates that the story recounts more than live up to this promise, filling their days with erotic fashion photography shoots and experimental filmmaking, punk shows, and new lovers. Visually, the story is a far cry from the crowded apartment on Mott Street where three children learn the limits of love. But both stories find their characters in orbit, albeit a precarious one, around family making; the difficulty of defining oneself in opposition to one’s parents, or the special kind of dependence that forms among young people when they no longer feel held by those who were meant to protect them.

It feels rare for a single book to do so many things, and to do each of them so well: an unrequited queer Olympic love story, a woman transformed by the designer clothes of a dead model, an aging machine, teenage violence, sexual yearning, unwanted marriages. Each vignette is magical, and critically real. It’s a gift to read something so attentive, able to traipse across time and space with the utmost care for each life brought into focus.