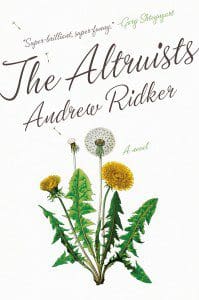

It’s hard not to see Andrew Ridker’s acerbic, cerebral first novel, The Altruists (319 pages; Viking)—which has attracted attention from NPR and The Times, among others—as an answer to the question of how to think about, let alone write about, a major strain of American life in 2019. The plot centers around a family at once archetypal and painfully real: Arthur, a pedantic, regret-filled professor who finds tenure elusive; his psychotherapist wife, Francine, whose premature death from breast cancer was worsened by Arthur’s cheating on her in the terminal stages of her illness; their daughter, Maggie, a sanctimonious, kleptomaniac tutor; and their son, Ethan, an isolated gay man who squanders his inheritance on luxurious distractions. Years after Francine’s death, Arthur invites his estranged children back to the family home in St. Louis, a gambit driven less by his desire for reconciliation than by the threat of foreclosure on the house that he hopes will function as a haven for him and his lover—an outcome he might avoid if only Maggie and Ethan would put their inheritances toward his cause.

It’s hard not to see Andrew Ridker’s acerbic, cerebral first novel, The Altruists (319 pages; Viking)—which has attracted attention from NPR and The Times, among others—as an answer to the question of how to think about, let alone write about, a major strain of American life in 2019. The plot centers around a family at once archetypal and painfully real: Arthur, a pedantic, regret-filled professor who finds tenure elusive; his psychotherapist wife, Francine, whose premature death from breast cancer was worsened by Arthur’s cheating on her in the terminal stages of her illness; their daughter, Maggie, a sanctimonious, kleptomaniac tutor; and their son, Ethan, an isolated gay man who squanders his inheritance on luxurious distractions. Years after Francine’s death, Arthur invites his estranged children back to the family home in St. Louis, a gambit driven less by his desire for reconciliation than by the threat of foreclosure on the house that he hopes will function as a haven for him and his lover—an outcome he might avoid if only Maggie and Ethan would put their inheritances toward his cause.

More than a family saga, The Altruists is a story of grief contaminated by manipulation, of spiritual fulfillment and moral aspiration constrained by the material world, of the fire of idealism smothered by the wet blanket of pragmatism. It’s a novel, in other words, rooted in the philosophical issues that have come to define the American left in the second decade of the second millennium. Arthur’s tortured, high-strung demeanor has its origins in a failed humanitarian project that, rather than improving a nation’s quality of life, caused some its citizens to die. Maggie, at once his foil and carbon copy, is similarly, if less consciously, frustrated: her acute moral intuitions roam in search of the sophistication needed to contextualize them and the fortitude needed to put them into practice. The Altruists looks long and hard at the aftermath of loss, just as it looks long and hard at class relations, financial anxiety, and the tensions of globalism, cosmopolitanism, and loneliness. Despite the leadenness of these topics—or maybe because of it—it’s very, very funny. It marks the beginning of what promises to be a rich career.

We met in Ridker’s living room in Iowa City, where he attends the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, about a week after The Altruists was released. Outside, months of snow had just begun to melt.

ZYZZYVA: Firstly, I should just say that I loved this novel. I thought, the whole time, that it reminded me of everything I like about Gary Shteyngart and writers in that vein. The touches of realistic absurdity here and there—a world where there’s a dating app designed to match people based on their trauma, stuff like that. It’s too real.

Andrew Ridker: It’s almost real. It’ll be real in six months.

Z: And other things like the name of the Dedbroke Performing Arts Center—these on-the-nose but funny intrusions of the absurdity of the facts of things, made explicit parts of the contours of the characters and their world.

AR: “The absurdity of the facts of things” is a good way to put that, I think, because it speaks to this idea of realism versus satire. I think the novel is satirical, but it’s not a satire. If you carefully select enough true details, you get an absurd picture, but it’s not one that’s been falsified or even exaggerated.

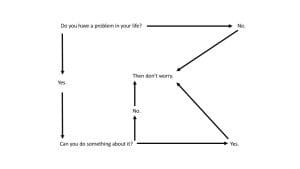

Z: I wanted to ask you about the flow charts, equations, and logical diagrams that illustrate snapshots of the characters’ thinking. They’re funny—and I think effective, insofar as they reveal new things about the psychological states of the characters. How did you figure out how to make that work?

Z: I wanted to ask you about the flow charts, equations, and logical diagrams that illustrate snapshots of the characters’ thinking. They’re funny—and I think effective, insofar as they reveal new things about the psychological states of the characters. How did you figure out how to make that work?

AR: It’s like this Rashomon thing. If six people watch someone slip on the ice, everyone’s going to remember a different aspect of that event. One very empathetic, caring person might say, “Oh, I immediately felt so bad for that person and hoped they were OK.” A more bitter, cynical person might snicker under their breath and say, “He was wearing AirPods, he got what was coming to him.” Everyone’s going to notice something different. I think the things I notice are the funny details that live at the intersection between intention and reality. One of the flow charts in the novel, for instance—that’s a flow chart on the refrigerator in my childhood home. It’s basically a roadmap to calming down during an anxiety attack. It’s well-intentioned but absurd. Of all the ridiculous things pasted up on my childhood fridge, that’s the one that stuck out, you know?

Z: So it’s more the juxtaposition of actual, found details than invention, per se.

AR: Maybe the word is “selection”—selection of details. I’m thinking about realism, and what a boring term that is. The stuff I like to read tends toward realism—I’m not always one for genre-mashing and hybrid work. It’s fine; it’s just not my taste. But the term “realism” sounds so boring, and there is, in fact, so much boring realism, where the mission seems to be to represent reality in this mimetic way. But I already have my boring life. I don’t want to go read a book about another boring life, and, I don’t know, the quality of the light through the window. That doesn’t interest me. So then the question becomes, how do you make realism interesting? You select the most interesting details from reality; you exaggerate a little bit; you live within the plausible, but you highlight the most implausible features. Everything in this book is realism, but it’s not my priority to have the reader feel the grit of the gravel under their shoe. It’s nice when writers can do that, but you can walk outside and walk on gravel if you want to feel what gravel feels like.

Z: It seems to me, though, that you do have a lot of apt sensory details, and some nimble, psychologically associative journeys that happen in the span of a paragraph or two that seem to borrow from a tradition of introspective, psychological realism. To go back to the use of visual aids, though, I just think it’s great how in the scene where Ethan and Arthur are driving home from the ballet, Ethan sees that logical chart of implication, “Gay –> Ballet.” It’s playful but also fitting—it captures Arthur’s reductive tendencies so well, as opposed to just telling us that Ethan realized his dad thought, simplistically, that he’d like ballet because he’s gay.

AR: I’ve always been interested in these more pyrotechnical aspects of fiction, whether it’s charts, or equations, or whatever—typographical play. But I’m also skeptical of them. When it’s bad, it’s so bad, and I don’t want to do it for its own sake. At its best, this kind of play lets you see something in a new way. At its worst, it’s like a poem about Christmas in the shape of a tree.

Z: Which James Merrill actually wrote. And published in Poetry.

AR: Was that James Merrill? I like James Merrill. That’s too bad. To your point about sensory detail, though—when I hit good sensory details when I’m reading, it is like a breath of fresh air. That is what the wind feels like on a certain kind of day. But it’s important for me that those details be used sparingly. In fact, I’ll usually write a whole scene without sensory details, and I have to remember to go back and put them in. Because I think they are valuable, in small doses; they can really bring a scene to life. But they’re my last thought. I have to do the psychological stuff, the observational stuff, the character stuff, the plot stuff, and then I’ll go back and say, “Oh, it’s kind of a colorless scene. Let’s put a little bit of sensory stuff in there.”

Z: One of the novel’s most pleasurable aspects, aesthetically, was its muscularity. The language was torqued in all these ways that seem connected to poetry, which I’ll ask you about in a minute. I find I’m allergic to novels that are just plot, or just declarative, step-by-step descriptions of action. Even if they’re statements of immense psychological intricacy, if there’s not some sort of texture—

AR: Texture! That’s exactly it.

Z: If there’s not anything of that nature, then even if the story is objectively riveting—something I’d listen to closely if it were told to me at a party—I’ll have a hard time finishing it. That might be my failure. I’m not sure whose failure it is. So I thought your careful balance of straight dialogue, straight plot, really luscious description, and then, often, a hybrid of those was well pulled-off.

AR: Balance was key for me in this book. Texture, plot, character, humor—keeping everything in balance was important. Of course, so many great works of art throw balance out the window; we don’t read Thomas Pynchon for balance at all, we read him for a few key things turned up to 11. At times I thought, “Well, is balance an artistic virtue, or is it a way of keeping yourself in check and not taking risks?” But at the end of the day, I prize books that care about balance. I was thinking today about Edith Wharton, and the way she’s got her social commentary, her characters, her plot, her setting. Everything is happening together in an orchestrated way, and ultimately that’s the kind of stuff that gives me, or at least gave me, in my childhood, the most pleasure.

Z: While we’re talking about balance, it seemed like The Altruists made use of a classical, Aristotelian conception of dramatic action. I tend to find that kind of thing artificial—or if not artificial, less than compelling—in realist work because, when not done properly, it doesn’t seem to take heed of the way that contingency unfolds in life. But The Altruists does, I think, in lots of ways. There’s a problem; there’s a climax; there’s a kind of resolution. But none of it feels manufactured or foretold, in the way that, say, formulaic Greek tragedies do. With respect to what you said about Pynchon, or other great works that Western theory would classify as “unbalanced,” some classical East Asian novels come to mind—The Tale of Genji, Cao Xueqin’s The Story of the Stone. These long, rich novels with no single unifying plot; there are crescents of plot arcs here and there, but they’re more collections of mini-sagas strung together by things like voice, texture, the history of a specific live or lives.

AR: I’d love to write a book that is less “balanced.” In fact, I think that’s the direction I’m heading. But I think what a sense of balance gave me, the first time out, were bounds to play in and around. Instead of bushwhacking through the wilderness, it was much more like assembling a gingerbread house.

Z: I want to return to these visual devices that appear a couple of times, either as depictions of something the characters are seeing or as roadmaps of their minds. I don’t want to overemphasize them, but I think they’re the more prominent manifestations of a broader tendency you deploy in the novel of having the narrator be meta-aware. I don’t know much about the history of that kind of narrative play in satirical realist novels, but I was curious if you saw any antecedents to your narrator, or if you could say something more about where you’re coming from, in terms of the satirical tradition.

AR: It’s very old-fashioned. There’s a prevailing wisdom today, one that’s taught here at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, that point of view is super important—which of course it is—and you should always be lodged in the character’s point of view, and what the character sees and thinks should be consistent with who they are. There’s truth to that. But there are these older novels, like The Red and the Black, where the voice of the author descends every now and then to pass judgment, fill in details, or tell you something about the character that the character doesn’t know about themselves. There’s a school of realism that says the book can’t be smarter than the character. But that’s not who I am. I think a lot about how different traditions inform aesthetic choices, and it makes sense to me that there would be this predominantly white, middle- or upper-class development in American literature that prizes subtext, understatement, the subtle symbol. But nothing in my family is subtle or subtextual. If someone has a problem with you, they’ll come right out and say it—actually, they’ll shout it so everyone can hear. I come from a Jewish family that talks with their hands, shouts a lot, and is very animated. So it’s no wonder my narrator’s voice has some attitude in it. I’m not coming from a family where dinner table conversation was silent and repressed, and everyone sat around clinking their silverware and simmering.

Z: Someone else in that vein who comes to mind is Maupassant, who we’ve talked about before. He seems like one of those authors who’s smarter than his characters, though his presence above his stories is far more relentless and severe than yours.

AR: Maupassant is a great example. I was also thinking of Nell Zink’s novel, Mislaid, which is a throwback to these older novels. I read that while writing The Altruists, and said to myself, “Wow, I can’t believe she got away with that.”

Z: I’m not sure how appropriate that kind of repressed realism you just mentioned—if we can polemically call it that—is to huge swaths of our culture right now. The Alter family seems to belong to one stratum of society for which it’s not. With a few exceptions, everyone’s wearing their emotions on their sleeves. It seems appropriate for the narrator to be a little flippant, too. If these same events were described in a Carver-esque way, I’m not sure I’d buy it, because I’m not sure that kind of voice could capture the zeitgeist, this theme of wanting to epistemically or morally outsmart everyone around you, which seems to be the preoccupation of several of these characters. The narrator’s playing the game, too.

AR: I think you’ve summed it up best just now. The narrator’s in on the game. Everything’s so crazy right now—it just doesn’t seem like the time for a nice, quiet, respectable realist novel full of small asides and quiet subtext. That stuff’s fine, but it doesn’t feel like our moment.

Z: How were you thinking about the relation of the tragic to the comic in the novel? There was a point while reading The Altruists where I began to think things were going to end dismally for the Alters—that, despite its playfulness, the book would close by pivoting to the failure of all these frustrated, immature people to make good on a last opportunity for mutual happiness. I would’ve believed that.

Z: How were you thinking about the relation of the tragic to the comic in the novel? There was a point while reading The Altruists where I began to think things were going to end dismally for the Alters—that, despite its playfulness, the book would close by pivoting to the failure of all these frustrated, immature people to make good on a last opportunity for mutual happiness. I would’ve believed that.

AR: There was a version of the book where that happened. But I don’t know what a book about three people who go from estrangement to further estrangement would mean, necessarily. But by that same token I was not prepared to wave a magic wand and make everything OK.

If you look at those last couple of pages, everything is a bit mixed. And my favorite endings have always been mixed. The end of The Graduate, where their faces fall on the bus, or the end of The Corrections, even, where Enid decides to make changes in her life—but the subtext is that she’s in her late 70s or whatever, and it might be a bit late for that. At the end of The Altruists, I wanted to give the characters the chance to redeem themselves without forcing them to redeem themselves. They should be able to sit in a room together. But no one’s any closer to knowing how to live a good life. They’re closer to possibly understanding each other, but the central philosophical question of the book isn’t resolved.

Z: Would you feel comfortable talking about how that kind of philosophical or intellectual concern came into the process of writing this consciously, if it did? Or whether a character like Maggie just seemed such a natural representation of a certain kind of person from our generation that you didn’t have to strain to invent her? I’m curious how much of this is conscious allegory. I think it’s believable either way. You nailed a morally confused and mean, but ultimately well-meaning, type of person.

AR: Whether you find yourself annoyed or charmed by Maggie probably depends on whether you see yourself or people you know in her or not. She can be obnoxious at times, but I don’t think her political views are “wrong” per se. She doesn’t have a nuanced understanding of things, and she’s a kleptomaniac and hypocrite, but she’s on the right side of history in a broad sense.

I was raised in a left-wing, Reform Jewish belief system that says it’s the responsibility of the privileged to help others. Of course, how one actually does that becomes a much trickier question. And of course, writing can be a very selfish act. When the world’s on fire, how do you justify that?

For me, it was just easier to unburden myself of those responsibilities by letting these fictional entities try to work them out, as I’m trying to work them out. I don’t begrudge any of them their impulses, intentions, or desires. They, like me, don’t know where they’d be best used. As absurd as they can be, I’m not mocking these characters; in many ways I don’t know any better than them.

Z: I thought it was timely how often cruelty figured into Arthur and Maggie’s attempts to shame each other into doing their version of the “right” thing. It was this added ingredient to the deep conflict you’re talking about, which is both epistemic and practical—how do you even know what the right thing to do is? But regardless of whether that question is settled, there’s still this practical question of whether you can manage to improve the world in the ways it needs to be improved. I thought the moments in the novel that either captured or referred to episodes where people purportedly committed to some noble cause were actually hurting their friends and fellow citizens captured something about millennial activism.

AR: Especially timely when a lot of well-meaning white activists, or wannabe activists, are being told that they need to listen or take back seats. They’re being told that, by all means, they should come to, say, Ferguson to help, but they should listen to the people who actually live here. This situation of a very well-meaning, fired-up white person flying across the country to help out and then being told, quite sensibly, to take a back seat and listen—that person’s pent-up energy is inherently comic to me. They’ve come all this way to stand at the front of the line, and they’re being asked to stand at the back. I’m not trying to judge those people; by showing up to protests and rallies they’re already doing a lot. But I do think there’s something inherently comic about this white, upper-middle-class compulsion to “help,” and the way your ego gets challenged when you’re told you’re not allowed to help, or that you shouldn’t help in the way you want. It’s just funny to me.

Z: One of the questions the book is toying with, besides the question of how to do good when there are all these unjust systems operating, is this question of to what extent people are defined or constituted by their trauma. You have this scene where Ethan steps into the chapel on the Danforth campus, and a speaker is giving a talk about how he went from being bullied in high school to being a millionaire, and it’s all tied to this weird monetization of trauma in an app that matches people based on their trauma. This idea that people are, in some way, their trauma, seems to be a question people today are answering affirmatively, to some extent. On the one hand, they’re doing so in an emancipatory way; they’re saying, “This is a part of me that you can’t take away, and it needs to be addressed.” But then there’s also this problem with essentialism, reductiveness, and the commercialization of trauma. What got you thinking about these issues, since so much of The Altruists has to do with the characters’ past traumas, and how they deal with them, or not?

AR: These are issues that people our age are encountering all the time. This question of self-definition is, I think, the question for millennials. Are you defined by your traumas? Are you defined by your consumer choices? Are you defined by your political ideology? I think there used to be a time when the dream of the future was that everybody would be free of labels. Everything’s a spectrum, and everyone’s on it in such a blurry way that we don’t need labels anymore. But in fact what we’re seeing is a return to labels. I’m not so much knocking the idea that you’d define yourself by your trauma as I am the fact that the systems we live under commodify that trauma, and ask us to perform it constantly.

Z: There’s a moment in the novel where Arthur criticizes this kind of thing—being a reductive identitarian.

AR: He basically says, “There’s such a thing as Zionism, but not a Zionist. Vegetarianism, but not vegetarians.” His idea is that ideologies exist, but people aren’t reducible to ideologies. Arthur was fun in that way. He could say all these politically contrarian things—but also, look who’s talking. It’s Arthur. You’re not supposed to listen to what he says.

Z: He loses a lot of credibility when he goes off on that too-eager, too-morally earnest student at the beginning of the novel. Which is a great scene. And then there’s the scene where Ethan arrives at Danforth and decides not to be a part of the social and academic groups there that center around queerness. I thought that was totally refreshing; it captured some experiences that I’ve had in higher education.

AR: I saw John Waters speak once, and he said something to this effect—something like, “I’ve always related to the outsiders. Even within the outsider community I’m on the outside, and that’s where I’m most comfortable.” I relate to this impulse of wanting and needing the group, but also defining yourself against it.

Z: Could you talk about what it was like to write a novel that was in some respects autobiographical? My sense is that it’s something a lot of people do in their first novels, and I was wondering if you have any thoughts on why that is. And the other thing I wanted to ask you about, whether in connection to that or not, is your background in poetry, and what coming out of poetry and writing this book was like. You chose a Mary Jo Bang quotation for the epigraph, which makes me think that poetry has some close connection here.

AR: In a lot of ways, the manuscript I’m working on now is closer to what would be considered conventional for a first novel, in the sense that it has a first-person narrator whose biography is very close to mine. In The Altruists, there are parts of me in every character, but it’s still in the third-person. There are a variety of ages, genders, sexualities, time periods, and places I’ve never lived or been to. I’d set up a fictional scenario with fictional people, and then I’d reach for a detail from life. It was a fictional enterprise dusted with the facts. If this were a first-person novel, I might feel more defensive and insistent on the inventedness of it, but no one is accusing me, a 27-year-old guy, of writing straight autobiography in a novel that doesn’t have a 27-year-old guy in it.

The Altruists is autobiographical in the big, abstract, important ways, in its themes and politics and philosophy. And it’s autobiographical in the nitty-gritty ways—as in, the university’s architecture resembles a real university’s architecture. But otherwise, it’s fully invented. Nevertheless, those are the two levels where I want fiction to be real: I want to feel that the author knows what they’re talking about, on the level of detail, and I want to feel like the themes are personal to them. Everything else? The scenarios—invented. The people—invented.

I really like the poetry question because, when we met ten years ago at Amherst, we were both young, aspiring poets. I don’t think I have the brain for poetry. The things I’m interested in just lend themselves to prose. But I had this formative seminar with Mary Jo where she’d make erasures out of my poems—I’d turn in a poem, and she’d cross stuff out and hand it back to me. And she’d have made a beautiful poem out of what I turned in. She was trying to teach me a lesson about cutting what wasn’t interesting or necessary. But I could never quite get there on my own with poetry, even by erasing myself. I couldn’t quite get to that place where I was just writing the poem. But what I think poetry taught me was the value of economy—of meaning, of motion. Sound, too. When I’m writing, I’m thinking about the sounds of words, and the rhythms of sentences. It’s not a Nabokovian obsession with language and sound; it’s just under the surface, but it’s there. I’m thinking a lot about how a sentence sounds next to another sentence, or if there’s an internal rhyme somewhere. It’s really quiet and low-level in the finished piece, but when I’m writing it’s at the front of my brain.