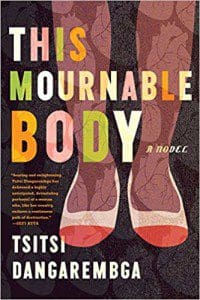

Set in the wreckage of a devastating war for independence, Tsitsi Dangarembga’s latest novel examines the impacts of race, class, and gender in post-colonial Zimbabwe. This Mournable Body (296 pages; Graywolf Press) returns us to the story of Tambudzai, the protagonist of Dangarembga’s previous two novels –– the critically acclaimed Nervous Conditions and The Book of Not. The novel opens with Tambudzai barely getting by, living off the remains of her savings from an advertising job and desperately looking for accommodations. Her goal is to move out of the ragged youth hostel she’s stuck in (despite being past the hostel’s age limit).

Set in the wreckage of a devastating war for independence, Tsitsi Dangarembga’s latest novel examines the impacts of race, class, and gender in post-colonial Zimbabwe. This Mournable Body (296 pages; Graywolf Press) returns us to the story of Tambudzai, the protagonist of Dangarembga’s previous two novels –– the critically acclaimed Nervous Conditions and The Book of Not. The novel opens with Tambudzai barely getting by, living off the remains of her savings from an advertising job and desperately looking for accommodations. Her goal is to move out of the ragged youth hostel she’s stuck in (despite being past the hostel’s age limit).

Even with a college degree and the hope of opportunity following Zimbabwe’s newly achieved independence in 1980, Tambudzai struggles to scrape together a living in Harare. Eventually she finds lodging in the boarding house of a widow and work as a high school biology teacher, though none of this is in line with her personal ambitions. After various incidents, Tambudzai takes an opportunity from a former foe that lands her in the blossoming “eco-tourism” industry. Though Tambudzai’s professional ventures serve as an attempt to run away from her village origins, the inadvertent result of these experiences is a long postponed homecoming.

Tambudzai’s story is one of Sisyphean perseverance in the face of obstacle after obstacle. One imagines Tambudzai would be (justifiably) full of resentment: she quit her professional advertising job after her white colleagues constantly took credit for her work, her circumstance as a poor middle-aged black woman do her no favors, and her every success is narrowly achieved and difficult to maintain.

The resultant portrait of Tambudzai and, by extension, Zimbabwe proves both devastating and haunting. Dangarembga’s prose is viscerally arresting, and her scenes are often disturbing. In the first few pages, Dangarembga goes into graphic detail when Tambudzai finds herself part of a crowd harassing a woman (who turns out to be a hostel-mate) as her clothes are ripped off and she becomes the target of rocks and other “missiles”:

The sight of your beautiful hostel mate fills you with an emptiness that hurts. You do not shrink back as one mind in your head wishes. Instead you obey the other, push forward. You want to see the shape of pain, to trace out its arteries and veins, to rip out the pattern of its capillaries from the body.

Dangarembga writes in the second person, and though the reader is aligned with Tambudzai in this manner, it doesn’t always engender sympathy, given her harsh pragmatism and bitter nature. The novel is psychologically tense, and Tambudzai frequently faces dark and difficult choices. She is at times a victim of the culture of violence and at others a complicit perpetrator.

To that extent, she questions her own values and that of nascent Zimbabwe, which in late July held its first elections since 1987 without Robert Mugabe already serving as president. Dangarembga examines what it means to be a Zimbabwean, both the positive and the negative. The culture is one that emphasizes strength and tenacity, but the tough exterior also excuses and allows abuse. When Tambudzai sees her cousin’s emotional reaction to finding out that the teacher is hitting her child, she considers it evidence that Nyasha is no longer a true Zimbabwean woman. “Weeping alongside a first grader–even nearly doing so–is a nauseating act of ghastly femininity,” Dangarembga writes. “You have no desire to expend energy on sympathy for a minor matter of corporal punishment. Women in Zimbabwe are undaunted by such things.”

She searingly comments on the still-felt impacts of colonialism and capitalism on a country recovering from immense turmoil, where, though the war is over, injustice remains and prospects are bleak. Amid the ensuing disillusionment and hopelessness is Tambudzai’s single-minded quest for monetary success—the idea that to be “somebody” requires leaving one’s heritage in favor of a more Westernized identity, and with that “the constant tension from not knowing whether or not you were as you were meant to be, the brutal fighting to answer affirmatively that question, and its damage.”

Ultimately, This Mournable Body is a reflection on the past, and how it can define us. Reckoning with horrific acts she’d rather push away, Tambudzai is caught in a struggle between the deep urge to forget and the stifling inability to do so. The eventual return to her home village will force her to decide what the value of one’s heritage truly is.