Tony Hoagland, like Jack Spicer, is a master of wielding the needle of irony to inject you with the pain of being an aware human being. (Re-reading Spicer’s letters to Graham Macintosh in the July 1970 issue of Caterpillar reminded me of their shared sensibility.) Hoagland has a particular ability to pinpoint the ills and contradictions of the American psychic landscape using deadly serious humor. This was already evident in poems such as “Hard Rain,” “Dickhead,” “Foodcourt,” “At the Galleria Shopping Mall,” and “America.” Perhaps no one else in the contemporary poetry landscape creates such pitch-perfect expositions of our national yearnings, naiveté, and delusions. He also has poems of infinite tenderness, such as “Beauty” or “The Color of the Sky.”

Tony Hoagland, like Jack Spicer, is a master of wielding the needle of irony to inject you with the pain of being an aware human being. (Re-reading Spicer’s letters to Graham Macintosh in the July 1970 issue of Caterpillar reminded me of their shared sensibility.) Hoagland has a particular ability to pinpoint the ills and contradictions of the American psychic landscape using deadly serious humor. This was already evident in poems such as “Hard Rain,” “Dickhead,” “Foodcourt,” “At the Galleria Shopping Mall,” and “America.” Perhaps no one else in the contemporary poetry landscape creates such pitch-perfect expositions of our national yearnings, naiveté, and delusions. He also has poems of infinite tenderness, such as “Beauty” or “The Color of the Sky.”

The best of Hoagland’s work shows his fearlessness, his willingness to probe his own demons, to expose himself in print. In the poems “Lucky,” “Sweet Ruin,” or “Phone Call,” for example, he dramatizes his own darkness, admits he is implicated, doesn’t shrink from self-exposure. He opens himself up in a profound way—the way letting light into a dark room allows you to see, and re-evaluate the tattered, rather humiliating furniture. (This has not been without controversy. His reaction several years ago to Claudia Rankine asking him about his poem “The Change” provoked a scathing response from Rankine, which you can read about here.)

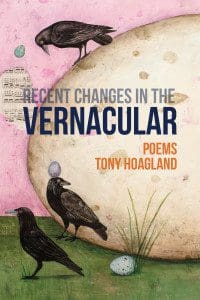

His latest book, Recent Changes in the Vernacular (96 pages; Tres Chicas Press), displays these same qualities—humor, perceptive exploration of the American psyche, and a willingness to go deep into the unexplored personal. It’s tempting to quote whole poems; to let them speak for themselves, because it’s hard to get a sense of their range and depth in short bursts. Part of Hoagland’s technique is the layering of imagery, one sequence playing off the next. But other skills include the ability to create a simple exposition that exactly captures something you instantly recognize. In “Opening Night,” a poem about the opera house built by the generosity of the widow of an arms manufacturer, he comments:

… no one smells the gunpowder

hidden deep inside the curtains;

No one sees the blood congealed

around the legs of the piano

These lines seem simple, straightforward, inevitable. But the effect they produce is almost impossible to achieve. Like a skilled tightrope walker, Hoagland makes his acrobatics look easy. Hoagland notes in his poem, “Empire”:

It’s hard to write inside an empire.

The ink is made from the eyelids of mice…

You don’t say anything because you like your job;

you like your car and wife and life.

Yet somehow Hoagland can write about the empire from inside it, write of his own role within it, of his complicity, which makes us aware of our complicity. His vision is accurate, wry, unflinching. This excerpt from “Moisture” is typical:

The ice skater spins on her prosthetic leg, on national TV,

in her first performance since the accident

and wobbles once but does not fall,

as the audience rises to its feet to give her an ovation

and my tears drip down into my potpie chicken dinner

saving me the trouble of adding salt.

His ability to pick just the right detail—the potpie or the eyelids of mice—elevates the poems and gives them power.

Of course, not every poem hits its mark; some feel light, jokey, too easy. But as a whole, this book is a complex mix of pleasure and revelation. Who else could write a scene of a man dying of a heart attack in a bus on the way to Atlantic City and end it like this?

The tired state trooper can feel a headache coming on,

and the faintest sprinkle on his hairy arms, just a mist

descending from the shrouded Jersey sky,

just the faintest dreamlike of particulates…

—Now traffic will be stop and go

all the way to Party City—

that’s what he thinks, phlegmatically,

as a woman with cotton-candy hair

and what looks like a Corgi in her purse

stands up inside the bus

and slides down the aisle,

because there is a vacancy in Row Sixteen

and she feels lucky.

We are there with the tired trooper, the hopeful gambler, and that perfect detail—the Corgi in her purse. We are with them and of them, rueful observers as death exits down the interstate.

As for the personal, “The Age of Iron,” which opens Section II of this book, stands as one of Hoagland’s most masterful poems—one that I wish there were space to quote in its entirety. As it is, you’ll need to read the book.