With the approach of Halloween, we polled our staff and contributors about which literary works of horror (or of just plain ol’ spookiness) they’d like to point our readers to. From the progenitor of the macabre short story, Edgar Allan Poe, to the psychological stylings of Shirley Jackson and Joyce Carol Oates, these works display a keen understanding of the utter fragility of the human mind. It may be a well-worn genre, but horror retains its power to effectively probe our darker impulses and explore cultural traumas:

With the approach of Halloween, we polled our staff and contributors about which literary works of horror (or of just plain ol’ spookiness) they’d like to point our readers to. From the progenitor of the macabre short story, Edgar Allan Poe, to the psychological stylings of Shirley Jackson and Joyce Carol Oates, these works display a keen understanding of the utter fragility of the human mind. It may be a well-worn genre, but horror retains its power to effectively probe our darker impulses and explore cultural traumas:

Paul Wilner, ZYZZYVA Contributor: I generally stay away from horror literature – it’s a step above science fiction, but it still gives me, you know, the creeps. That’s the intention, of course, but it feels a bit…intentional for my taste.

But I make an exception for Edgar Allan Poe. Besides being the lead Goth of his time, inspiring everyone from Baudelaire to Lou Reed, there’s a hysterical realism to Poe’s prose that continues to be relevant, even incorrigibly modern.

The Poe story that has stayed with me most is “The Tell-Tale Heart.’’ First published in 1843 in The Pioneer, a magazine edited by James Russell Lowell, a poet about as far from the aesthetic of the bard of Baltimore as it’s possible to imagine.

In it, the unreliable narrator recounts the “perfect crime’’ of murdering the old man who lives in the house they share, whether as a servant or family member.

Poe strikes the High Romantic note from the outset.

“True! – nervous – very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses – not destroyed, not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad?’’

How, indeed? Let us count the ways.

Trying to explain his motive for the crime, he discounts the usual: “Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me…I think it was his eye! yes it was this! One of his eyes resembled that of a vulture – a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold…”

In the dead of the night, he falls on the old man with a shriek, pulls his bed down over him, dismembers him and buries his remains in the room. Move over, Hannibal Lecter.

When the police arrive – neighbors had heard the commotion – he entertains them cordially, confident “in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph’’ and places his chair above the spot where the corpse had been hidden. But as he tries to continue his small talk, he hears a sound, persistent and growing ever louder – the heartbeat of his victim.

“Was it possible they heard not! Almighty God! – no, no! They heard! – they suspected! – they knew! they were making a mockery of my horror! – this I thought, and this I think.”

Chattering in terror, he confesses, prefiguring a thousand Raskolnikovs.

Poe is considered the father of the detective novel, a banal ambition. But he was so much more. His excited sentences leap forth and grip us still, even in these short pages.

He anticipates Baudelaire’s famous challenge – “Hypocrite lecteur – mon semblable – mon frère,’’ and Rimbaud’s later derangement of the senses.

Found delirious on the streets of Baltimore on Oct. 3, 1849, he died a few days later. There’s an apocryphal report that the cause of death was “cooping’’ – a form of 19th century election fraud in which unwitting victims were kept in a room (or “coop’’) and plied with liquor until they voted, often several times, for a particular candidate. Or maybe he was just drunk, and took too many drugs – he never needed much encouragement in that regard.

Regardless, “The Tell-Tale Heart’’ still makes me shiver. I see Poe’s wild man, and his victim, in my mind’s eye. Wherever we may go, he is waiting.

Rebecca Rand, Intern: “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” is one of Joyce Carol Oates’ most famous short stories, and it is an incredibly eerie work of psychological horror. It recalls the experience of a teenager named Connie, approached by a creepy man who calls himself Arnold Friend, who she finds seductive in spite of herself.

Rebecca Rand, Intern: “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” is one of Joyce Carol Oates’ most famous short stories, and it is an incredibly eerie work of psychological horror. It recalls the experience of a teenager named Connie, approached by a creepy man who calls himself Arnold Friend, who she finds seductive in spite of herself.

When a character in any story utters the line, “You’re a monster!” to a human villain, it is usually after s/he has committed or promised to commit some inhuman act of violence. Oates manages to make Arnold Friend an incredible monster without any violence. We question his humanness because he is grotesquely phony. He has shaggy black hair that is “crazy like a wig,” a face covered in mask-like foundation makeup, a nakedly aged throat, eyelashes covered in tar, and boots stuffed to make himself look taller. His disguise is clumsy and careless–he trips over his obviously-stuffed footwear. Connie sees all this, know’s he’s a fraud, and yet he still exerts psychological control over her. This is part of what makes “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been” so freaking scary. And a perfect short read for this Halloween.

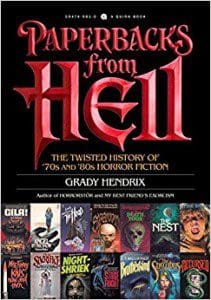

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: If you walked into a mall bookstore before the year 1995, chances are you saw them: the rows and rows of mass market paperbacks with evocatively rendered skeletons, masked killers, and insect hordes adorning their covers. While you may have thought that titles such as Night-Shriek, Toy Cemetery, and The Accursed – with their almost microscopic fonts and outlandish storylines – had been resigned to the dustbin of history, one man has made it his mission to preserve their dubious legacy. Grady Hendrix’s Paperbacks From Hell is both a survey of and a love-letter to the lurid horror novels of the 70’s and 80’s, skipping over the big names like Stephen King and Dean Koontz in favor of the lesser known and forgotten authors who contributed to the genre during the mass market paperback boom.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: If you walked into a mall bookstore before the year 1995, chances are you saw them: the rows and rows of mass market paperbacks with evocatively rendered skeletons, masked killers, and insect hordes adorning their covers. While you may have thought that titles such as Night-Shriek, Toy Cemetery, and The Accursed – with their almost microscopic fonts and outlandish storylines – had been resigned to the dustbin of history, one man has made it his mission to preserve their dubious legacy. Grady Hendrix’s Paperbacks From Hell is both a survey of and a love-letter to the lurid horror novels of the 70’s and 80’s, skipping over the big names like Stephen King and Dean Koontz in favor of the lesser known and forgotten authors who contributed to the genre during the mass market paperback boom.

While Hendrix’s deadpan, often ironic tone may not be to every reader’s liking, his genuine excitement when he stumbles upon a gem in the dusty stacks proves infectious. His enthusiasm is palpable as he describes the work of William H. Johnstone, whose novels routinely featured muscle-bound Vietnam vets battling Satan-worshipping deviants in small town America, as well as the more clinical and psychologically-driven stylings of Andrew Neiderman (his book Brainchild depicts what happens when a straight A science student turns her household into a laboratory maze for humans). Don’t be surprised if you come away from this book with your own wishlist of macabre titles to track down. An ideal read for the October season, Paperbacks From Hell serves as a nostalgic ode to a paperback era long gone and a reminder of the assorted treasures that might be lurking at your local used bookstore.

Laura Cogan, Editor: Literature and film are replete with depictions of the house as site of myriad terrors. Through all its variations, in essence there are two fundamental faces to this persistent nightmare: horror at the idea of our physical safe haven breached and corrupted, and (stemming from the profoundly resonant house-as-self allegory) horror at the idea of the unknown within our own minds, our sanity breached and corrupted. The call is coming from inside the house, runs the comically over-familiar line. Cliche, perhaps. But it still chills. Particularly when the call–or voice of the demon–is, by extending the metaphor, coming from within your own mind.

Laura Cogan, Editor: Literature and film are replete with depictions of the house as site of myriad terrors. Through all its variations, in essence there are two fundamental faces to this persistent nightmare: horror at the idea of our physical safe haven breached and corrupted, and (stemming from the profoundly resonant house-as-self allegory) horror at the idea of the unknown within our own minds, our sanity breached and corrupted. The call is coming from inside the house, runs the comically over-familiar line. Cliche, perhaps. But it still chills. Particularly when the call–or voice of the demon–is, by extending the metaphor, coming from within your own mind.

Throughout her body of work, Shirley Jackson situates horror squarely within the domestic realm, where it belongs–for cruelty begins at home. There are, it’s true, intimations of the supernatural in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, but they tell us more about our inimitable narrator than they do about the real horrors of the story. The horrors at the crux of the book are squarely quotidian: the cruelty and mob mentality of a small town; the potency of classism in American life; the tender devotion and seething resentments percolating under any family roof. Yet they are harrowing for all their familiarity. As Jonathan Lethem writes in his introduction to the Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition, “[Jackson] disinterred the wickedness in normality, cataloguing the ways conformity and repression tip into psychosis, persecution, and paranoia, into cruelty and its masochistic, injury-cherishing twin.” Castle is perhaps the most powerful distillation of Jackson’s chosen materials: a rich subtext of symbolism, dualities, and Jungian tropes give it the potency and inexhaustible quality of myth. Yet it resists the temptation to decode. The humanity of its central characters, the Blackwood sisters, is protected; aspects of their characters and motives are illuminated as the novel develops but are ultimately allowed to remain inscrutable.

And if we are unsettled reading it, it is worth noting that Jackson was unsettled writing it. A sinister sense of unease within the self, within the home, within the town are not just Jackson’s subject matter, but reflected just as eerily in the writing itself. As Ruth Franklin comments in her beautiful, generous biography, while writing Castle, Jackson was “disturbed … that she might not have control over her own fiction–that her work might mean something entirely different from what she intended.” Indeed, who better than a writer to understand and communicate the terror of the thoughts and words that come unbidden, the voice that speaks through me but is not, exactly, me?

Kailee Stiles, Intern: Once the supernatural is introduced into a story, the central problem is always identification–what is still ‘us,’ human, and what is now ‘them,’ the supernatural other? Put another way, a good horror story will eventually render characters–or audiences–unable to tell who is ‘infected’ and who isn’t. Enter Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a novel that thrives on its famously doubled protagonists: which one is diseased, the intelligent ‘creature’ assembled piecemeal or the human Doctor gone mad? The growing realization that Frankenstein’s monster is more like ‘us’ than we could ever admit lends the entire novel a cancerous unease. The brilliance of Frankenstein lies in both Shelley’s ability to tell a truly unnerving ghost story, full of bumps in the night, and her correct sense that horror rests in these blurred lines between humanity and inhumanity. Read this alone on a rainy night, and you’ll catch yourself in the mirror seeing the creature instead.

Kailee Stiles, Intern: Once the supernatural is introduced into a story, the central problem is always identification–what is still ‘us,’ human, and what is now ‘them,’ the supernatural other? Put another way, a good horror story will eventually render characters–or audiences–unable to tell who is ‘infected’ and who isn’t. Enter Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a novel that thrives on its famously doubled protagonists: which one is diseased, the intelligent ‘creature’ assembled piecemeal or the human Doctor gone mad? The growing realization that Frankenstein’s monster is more like ‘us’ than we could ever admit lends the entire novel a cancerous unease. The brilliance of Frankenstein lies in both Shelley’s ability to tell a truly unnerving ghost story, full of bumps in the night, and her correct sense that horror rests in these blurred lines between humanity and inhumanity. Read this alone on a rainy night, and you’ll catch yourself in the mirror seeing the creature instead.

Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor: The safest place in the world is a graveyard, my late grandmother used to say. That’s because the dead can’t hurt you. My grandmother’s indisputable maxim can run counter to the conceits of horror. But it does point us toward a different kind of fear, the kind where the supernatural plays no part, and even modern and all-too-real monsters such as the serial killer do not even figure.

Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor: The safest place in the world is a graveyard, my late grandmother used to say. That’s because the dead can’t hurt you. My grandmother’s indisputable maxim can run counter to the conceits of horror. But it does point us toward a different kind of fear, the kind where the supernatural plays no part, and even modern and all-too-real monsters such as the serial killer do not even figure.

Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster is the only book I’ve read that gave me nightmares. The horror encountered by the residents of Chernobyl in April 1986 is so powerfully conveyed—the pitilessness of it all: the fragility of our bodies, the tenuousness of our safety—it can invade your dreams. It touches on an unspoken terror we all harbor: that your family, your spouse, that your very community can be destroyed, and the world shrugs. Not as horrific, perhaps, but steeped in a sense of sorrowful helplessness before a leviathan of cruelty (if not evil) is Alexievich’s Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War. The barbarity of that particular war, as recounted by various interviewees, evokes revulsion. But it’s the accounts of so many mothers losing their young sons to a war they didn’t even know was being waged, unaware of the hell their boys were being sent to, that gives one fright. Indeed, what can chill the blood more than living in a society governed by a state that brooks no transparency, that won’t be held accountable for its actions, that has utter disregard for the well being of its citizens?

What a great roundup of horror fiction for the season! I am especially glad to see Shirley Jackson and Mary Shelley getting their due. “We Have Always Lived in the Castle” is second only to “The Haunting of Hill House” as a great horror novel, and “Frankenstein” is immortal on so many levels. I was disappointed, however, to see that no one mentioned the great Ruth Rendell, either under her own name or her pseudonym, Barbara Vine. “A Dark-Adapted Eye” is still one of the scariest thrillers I have ever read. But it’s a good reading list even without her. Thanks!