If you’re anything like the ZYZZYVA team, you occasionally like to spend Halloween curled up in front of your screen of choice for a frightening film (or two…or three). From Rosemary’s Baby to The Exorcist, we can’t help but observe the fact that many – if not most – of the iconic horror movies of the last fifty years have drawn their source material from the written word. In celebration of the holiday, we thought we’d recommend a selection of some of our favorite or under-appreciated horror movies adapted from works of fiction for you to check out.

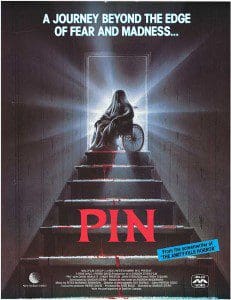

Pin: A Plastic Nightmare (1988) – Andrew Neiderman’s 1981 work Pin is not a great novel, but it’s one that continues to linger in the imagination of readers thanks to its genuinely strange premise and the way Neiderman conveys the cold, clinical psychopathy of its narrator, Leon. The story opens on the dismal childhood of siblings Leon and Ursula Linden, who face an overbearingly obsessive-compulsive mother and a cold, emotionally withholding father. The only comfort they find in their early years comes from each other and the medical dummy their physician father brings to life thanks to his prodigious gift for ventriloquism. Leon’s connection to the anatomical model, whom Ursula nicknames Pin (short for Pinocchio), turns out to be so profound that even into adulthood the sheltered young man is unable to connect with anyone outside his cloistered circle of Ursula and Pin.

Pin: A Plastic Nightmare (1988) – Andrew Neiderman’s 1981 work Pin is not a great novel, but it’s one that continues to linger in the imagination of readers thanks to its genuinely strange premise and the way Neiderman conveys the cold, clinical psychopathy of its narrator, Leon. The story opens on the dismal childhood of siblings Leon and Ursula Linden, who face an overbearingly obsessive-compulsive mother and a cold, emotionally withholding father. The only comfort they find in their early years comes from each other and the medical dummy their physician father brings to life thanks to his prodigious gift for ventriloquism. Leon’s connection to the anatomical model, whom Ursula nicknames Pin (short for Pinocchio), turns out to be so profound that even into adulthood the sheltered young man is unable to connect with anyone outside his cloistered circle of Ursula and Pin.

When Leon and Ursula’s parents are killed in a horrific car crash, Leon promptly moves Pin from his father’s practice to the sibling’s expansive but lonely estate, and the stage is set for a disturbing psychodrama worthy of Robert Bloch. Surprisingly, the film adaptation from director Sandor Stern (a filmmaker who has helmed more Lifetime movies than feature films) is remarkably faithful to its source material. While Stern perhaps wisely chooses to tone down the incestuous subtext and render Leon a more sympathetic but no less unhinged figure, the director proves most adept at conveying the suffocating air of privilege and mental decay in the Linden household, as well as the systems of abuse that can exist within a family. Aided by a dreamlike synthesizer soundtrack and a convincing turn from Cube’s David Hewlett as Leon, Sander’s version of Pin often brings to mind the moody and sterile-feeling horror of fellow Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg. Most importantly, this is one of those rare and relatively bloodless films from the genre that proves far more sad than gruesome, and Pin is all the better for it.–Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant

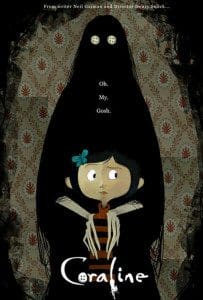

Coraline (2009) – Fair warning: if you’re terrified of spiders, dolls, or any combination thereof, this next film may not be for you! Coraline, based on a book of the same name by Neil Gaiman, is the story of a young girl who is unhappy about her parents’ decision to move to the dilapidated Pink Palace Apartments. That is, until she discovers a small door to a parallel universe in her new living room. Traveling through the portal, she finds an idealized version of her life on the other side: a place where her parents are more loving, food tastes better, and everything seems great. Of course it seems great, and of course it isn’t – darkness lurks underneath. Don’t be fooled by the movie’s childlike aesthetic, this is horror. The 3-D stop motion animation manages to employ some of the usual visual tropes of children’s cartoons – each character has an oversized head and eyes, for instance – without sacrificing the whimsically eerie atmosphere that Gaiman’s books are known for. Coraline is a visual treat, which makes it all the more riveting.–Rebecca Rand, Intern

Coraline (2009) – Fair warning: if you’re terrified of spiders, dolls, or any combination thereof, this next film may not be for you! Coraline, based on a book of the same name by Neil Gaiman, is the story of a young girl who is unhappy about her parents’ decision to move to the dilapidated Pink Palace Apartments. That is, until she discovers a small door to a parallel universe in her new living room. Traveling through the portal, she finds an idealized version of her life on the other side: a place where her parents are more loving, food tastes better, and everything seems great. Of course it seems great, and of course it isn’t – darkness lurks underneath. Don’t be fooled by the movie’s childlike aesthetic, this is horror. The 3-D stop motion animation manages to employ some of the usual visual tropes of children’s cartoons – each character has an oversized head and eyes, for instance – without sacrificing the whimsically eerie atmosphere that Gaiman’s books are known for. Coraline is a visual treat, which makes it all the more riveting.–Rebecca Rand, Intern

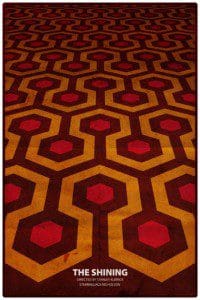

The Shining (1980) – Adapting a horror novel to film has got to be one of the most thankless tasks in writing. The sense of fear constructed by a novel’s omniscient narrator isn’t easily replicated in film, and dialogue that once crackled in our heads often turns bland when we hear it from an actor. So when anyone raises the stakes of the horror genre by taking the written word and exceeding our most terrifying literary imaginings onscreen, there’s little holding it back from becoming one of the best films –full-stop – of all time. Stanley Kubrick’s psycho-thriller adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining is one such film, required viewing for both cinephiles and horror junkies alike. Kubrick worked loosely from his source material (King is famously dismissive of the movie), re-imagining the world of the Overlook Hotel into a space where the inexplicable layers on top of the otherworldly to create a Möbius tapestry of fear. Perhaps most impressively, Kubrick married the slow-building terror literature excels at with the visual scares endemic to campy horror movies, creating an indescribable nightmare that exists outside any logic but its own. Kubrick and Diane Johnson’s eerie screenplay is taken to legendary heights by every member of the cast, even the one-time supporting appearances; I’ve been hearing “Play with us, forever” ringing in my ears since I first watched this film over a year ago.

The Shining (1980) – Adapting a horror novel to film has got to be one of the most thankless tasks in writing. The sense of fear constructed by a novel’s omniscient narrator isn’t easily replicated in film, and dialogue that once crackled in our heads often turns bland when we hear it from an actor. So when anyone raises the stakes of the horror genre by taking the written word and exceeding our most terrifying literary imaginings onscreen, there’s little holding it back from becoming one of the best films –full-stop – of all time. Stanley Kubrick’s psycho-thriller adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining is one such film, required viewing for both cinephiles and horror junkies alike. Kubrick worked loosely from his source material (King is famously dismissive of the movie), re-imagining the world of the Overlook Hotel into a space where the inexplicable layers on top of the otherworldly to create a Möbius tapestry of fear. Perhaps most impressively, Kubrick married the slow-building terror literature excels at with the visual scares endemic to campy horror movies, creating an indescribable nightmare that exists outside any logic but its own. Kubrick and Diane Johnson’s eerie screenplay is taken to legendary heights by every member of the cast, even the one-time supporting appearances; I’ve been hearing “Play with us, forever” ringing in my ears since I first watched this film over a year ago.

During much of the film, it’s almost impossible to even say what we’re scared of – there’s no easily named fear in many of the scenes, and fans have spent decades attempting to decode the symbolism in the film to work out Kubrick’s own nightmare-logic. But that’s the very point: fear is a feeling, floating in the air and through our minds, not a thing we can look at and name. We have nothing to fear, but fear itself. The best films coil back on themselves, evading explanation, over and over again with every repeat viewing; The Shining similarly locks us into its labyrinth, doomed to the endless loop of a dream. All we have to do is wake ourselves up.–Kailee Stiles, Intern

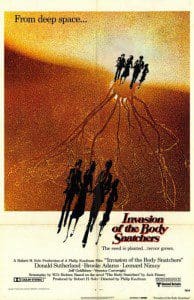

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) – Though it works perfectly on its own as a paranoid thriller and creepfest, Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (based on Jack Finney’s 1956 novel) has a particularly unsettling resonance for anybody who remembers San Francisco before 2000.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) – Though it works perfectly on its own as a paranoid thriller and creepfest, Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (based on Jack Finney’s 1956 novel) has a particularly unsettling resonance for anybody who remembers San Francisco before 2000.

The tech boom and its corrosive effect upon who gets to live here has bubbled forth a mucous pod of a metaphor for the 1978 movie that simply wasn’t there before. So as Donald Sutherland’s health inspector stumbles through the mystery of why people are acting so peculiarly, and as regular seeming working stiffs and suited businessmen start to gather conspiratorially, the eerie feeling that something huge is afoot—and that whatever it is it’s not good—can’t help but summon a dread that has nothing to do with being replaced by an alien species but everything to do with being replaced by a kid in a hoodie bearing a start-up logo.

Aside for its story, the movie can be watched for the nostalgia its setting evokes. San

Francisco is portrayed as something of an urban village full of working-class people.

For anybody who recalls the perhaps now lost egalitarianism of the city, it makes

complete sense that a couple of Department of Health employees, a poet (Jeff

Goldblum) who runs a mud-bath business with his wife (Veronica Cartwright), and a

famous psychiatrist (Leonard Nimoy) should all know and hang out with each other.

(Every other column by the late, great Herb Caen attested to this sort of thing.) Even

as the movie’s dastardly plot unfurls, the various moody shots of the city remind us

of a time when this was a beautiful place to which nobody driven by the need to

make millions in a hurry was especially attracted to.

But San Francisco is where they came just the same to make their fortunes, and the

city has pretzeled itself to accommodate this new reality. Disquieting enough,

Kaufman’s movie addresses the situation. At one point, one of the characters is

revealed to be a pod person, their human self replaced by the invaders from space.

“We came here from a dying world,” the creature informs us. “We drift through the

universe, from planet to planet, pushed on by the solar winds. We adapt and we

survive. The function of life is survival.”

Go to sleep and accept the inevitable is the advice being given. It’s painless. Wake up

in your new form. Then congregate down on the corner, wait for orders, and help us

spread through the rest of the planet. Everyone will adapt. But first they’ll die, and

then it’ll be as nothing changed.–Oscar Villalon, Managing Editor